The bottom line is that it’s not easy to give fresh light to a character who jumped so outrageously into the spotlight, and shuffled, dodged, and dived to make sure he stayed there. Come in, Ken Burns.

He has now turned to Ali. Spreading eight hours (divided into four episodes), “Muhammad Ali” took seven years to complete and features interviews with close friends, family, experts and cultural figures, selections of more than 15,000 photographs and intimate images that even the Ali’s daughter, Rasheda, had not seen before. So yes, you could call it complete. But still the question: why?

“He’s the best athlete of the 20th century,” Burns tells CNN. “I would love to sit on a bar stool and argue that he is the best athlete of all time: period, point and end.

“His life and his professional life intersected with all the main themes of the second half of the twentieth century, which has to do, obviously, with sport and the role of sport in society and also race. and politics, faith and Islam and war … He is just the most attractive figure in all sports. “

The director shares that he has a neon sign on the editing suit that says, “It’s complicated.” The same applies to Ali’s life. Alongside the family heroics, Burns gives a broad look to Ali’s ugly part (harassment, promiscuity). “There is no message” in the documentary, he insists, “we are in the business of history.”

“All human life is complicated and contradictory and sometimes controversial, but there is a majesty in this particular life, and I don’t think I’ve ever known an American as full of spirit and sense of purpose as (Ali) , ”Burns says.

Walking through Ali’s life is a well-trodden path for boxing fans, but due to the volume of material Burns had to deliver, there are still some surprises. Here are some of Ali’s lesser-known curiosities from the series.

Ali’s fear of flying was so extreme that he once carried a parachute

When a young Cassius Clay traveled from Louisville to San Francisco to perform Olympic tests, the amateur boxer was so afraid of flying that he bought a military parachute and took it in flight. When he won the competition, he pawned one of his prizes, a watch, to pay for a train ticket home.

Ali’s corner once put ice cubes in his shorts halfway through the fight

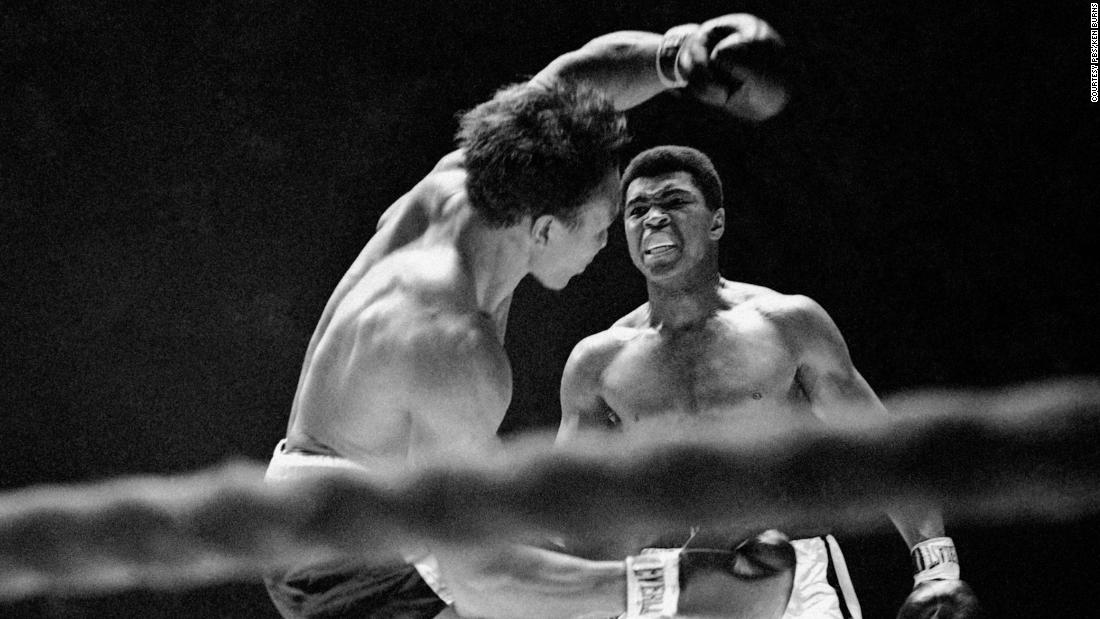

Fighting Henry Cooper in the United Kingdom in June 1963, Clay won the big left hook a few seconds before the end of the fourth round. The bell arrived just in time for the American, whose corner did his best to wake him up for the next round. That meant it smelled of salt under the nose and ice cubes for the shorts. It worked: he swung back and won in the fifth when the referee ruled that Cooper was too cut and bloodied to continue.

Before their bitter rivalry, Ali and Joe Frazier first met as friends

A young Frazier was 14-0 when he went into Ali’s workout and showed up. Ali said in two years he would fight the rise and the finish if he continued to do what he was doing and sent Frazier with an autographed photo. It took longer, but in March 1971 the two undefeated boxers finally met.

Racists sent Ali a beheaded dog by mail

Ali’s legal dispute over his refusal to fight in the Vietnam War is well analyzed in Burns’ documentary, including the horrific racist vitriol the boxer faced. Convicted of draft evasion in 1967 and stripped of his boxing license and title, Ali was forced to enter the boxing area during his early years. Before his fight back against Jerry Quarry in Atlanta in 1970, he was sent a box with a black dog beheaded inside and a note that said, “We know how to handle black dogs dodging shooters in Georgia.” Ali’s status as a conscientious objector would ultimately be justified when the Supreme Court unanimously overturned the 8-0 sentence in 1971.

When Ali lost to Frazier, Muammar Gaddafi declared a day of mourning

He was once given an Elvis Presley boxing gown

And he was pure Elvis of the 1970s. Ali wore the robe for his March 1973 fight against former three-inch American Ken Norton. White, covered in jewelry and with blue lettering on the back that said “People’s Choice,” the gift showed no good luck charm, with Norton causing Ali’s second professional loss.

Mobutu Sese Seko of Zaire confiscated George Foreman’s passport before “The Rumble in the Jungle”

After spending all that money funding “The Rumble in the Jungle,” the 1974 mega-fight between Ali and Foreman in Zaire (today, Democratic Republic of Congo), dictatorial leader Mobutu wouldn’t let anything stop him. Ali and Foreman trained in Zaire in separate camps before the fight. When Foreman was cut above the right eye in a fighting session, his doctor said it would take weeks to heal and asked for a postponement. The boxer wanted to fly to France or Belgium for a second opinion, but Mobutu said no; he had reportedly confiscated his passport. The fight was postponed for just over a month and the two boxers were left alone.

At the end of his career, Ali was dying his hair

Even the most casual boxing fans know that Ali kept boxing too long; his body was unnecessarily punished after his reputation as The Greatest. But in 1980, when a 38-year-old Ali entered the ring with Larry Holmes, he was showing his age and dying his black hair to disguise his gray. He did not back down the years: Ali was beaten by Holmes. “It was like watching a truck hit a friend,” sports writer Dave Kindred tells Burns.

He was a lover of magic

Ali met Fidel Castro in 1996, when the former champion was unable to speak in large part due to the onset of Parkinson’s disease. However, he was still an animator and therefore did magic tricks for the Cuban leader. But, believing that he was deceiving against Islam, Ali showed Castro exactly how he had done them immediately.

Originally, Ali did not want to light the Olympic flame in Atlanta in ’96

By the mid-1990s, Ali had taken a step back, though he traveled frequently to do humanitarian work. When the Atlanta Games secretly asked him if he would light the Olympic flame, he initially said no, citing the weaknesses that came with his advancement in Parkinson’s diagnosis. But his friend, photographer and biographer Howard Bingham, convinced him and said, “The world is saying thank you for everything you’ve done in your life. There will be a billion people watching it.” Ali’s surprise appearance remains one of the defining images of the Olympics.

Ken Burns’ “Muhammad Ali” premieres on September 19 on PBS.