Washington.- Every year tens, if not hundreds, or even thousands of Mexicans go through the American judicial system. Not all cases reach the media, not all have the same media coverage nor the same interest in public opinion. In this 2020, however, the big cases have had one thing in common: important figures and Mexican public charges have sat in the dock, an image of corruption in the country judged by the American Union.

If 2019 was the year of the culmination of one of the most anticipated trials: the conviction and sentence of Joaquín El Chapo Guzmán Loera, leader of the Sinaloa Cartel, one of the most famous drug traffickers in the world, a character of almost mythological aura; this 2020 the prominence has been shared by three political figures of different kinds.

Three cases that are like a story in three acts, depending on its ending.

Act 1: Genaro García Luna. What remains

The head of 2019, with Chapo already in a maximum security prison in Colorado, was expecting a surprise: the arrest in Dallas of Genaro García Luna, former Secretary of Security of the government of Felipe Calderón Hinojosa. And nothing more and nothing less than accused of drug trafficking with a bow on the Sinaloa cartel.

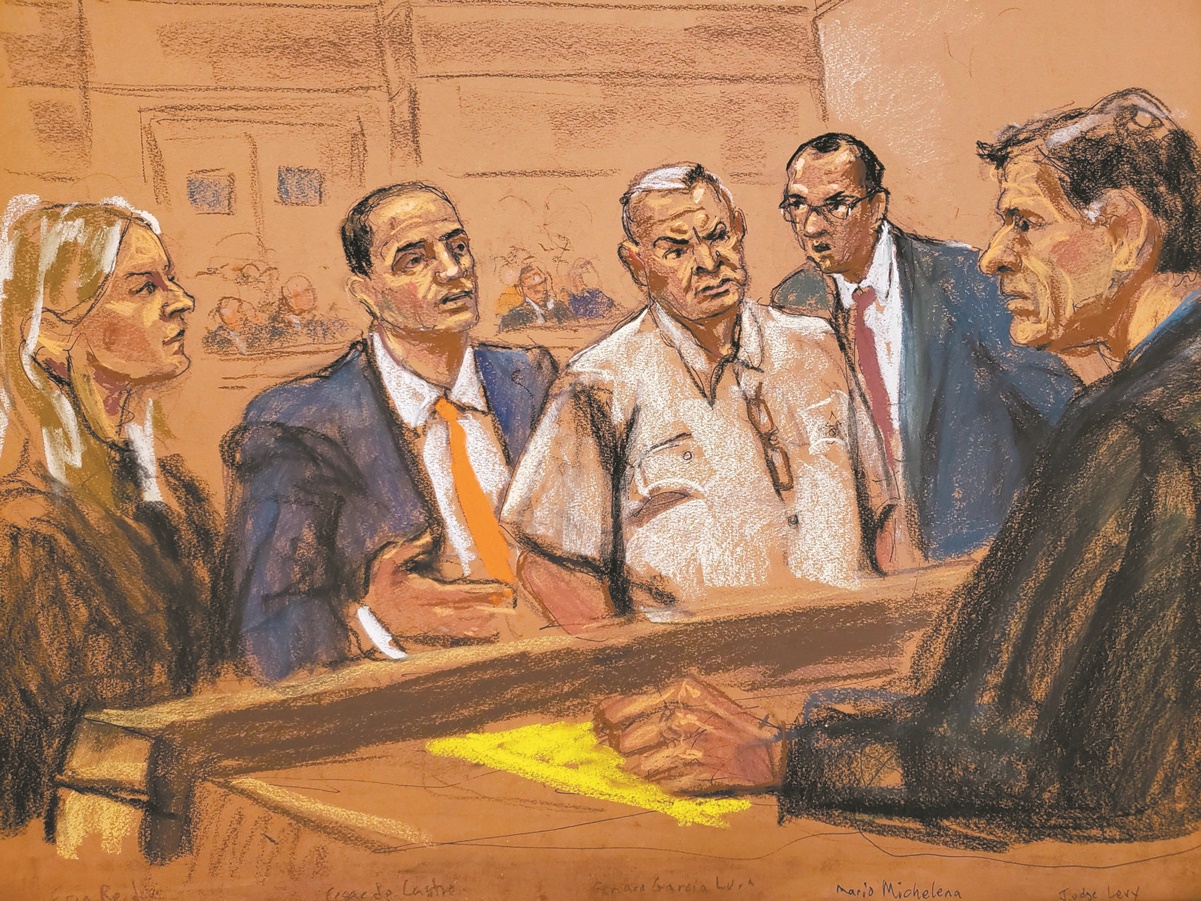

His first appearances before the judges, in pre-Coronavirus times, only served to plead not guilty and see how unsuccessful attempts to secure release on bail were, despite millions of proposals from his lawyer, César de Castro. . The “serious risk” of leakage prevented a different resolution; months later, reasons based on the pandemic situation did not take effect either.

His case was complicated by the link to the case of Ivan Reis Arzate, former head of the Federal Police and former Mexican liaison with the US Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA), who when a few days before the end of his sentence in Chicago to collaborate with the Sinaloa Cartel and be deported to Mexico, he was in New York accused in the same case as Garcia Luna.

To make matters worse, in the summer the crime of leading a criminal gang was included in the case, charges for which two high-ranking charges of the Mexican Federal Police were also charged: Luis Cárdenas Palomino and Ramon Petit, for leaving that the Sinaloa cartel acted “with impunity.”

With the constant refusal that García Lluna is negotiating an agreed exit with a guilty plea – a totally common public statement but not always true -, court hearings are now held by videoconference that have had serious and constant technical altercations, especially due to disability of voices in Spanish to mute their phones. Meanwhile, the parties are reviewing and analyzing the nearly one million pages of evidence and tens of hours of recordings that would implicate the former Secretary of Security in an unprecedented drug trafficking plot.

Act 2: Salvador Cienfuegos Zepeda. The one who escapes

Like the arrest of García Luna, the arrest of Salvador Cienfuegos Zepeda, who was Secretary of Defense in the government of Enrique Peña Nieto, was a major surprise. Cienfuegos landed in Los Angeles in late October for vacation and ended up handcuffed and bound for New York, accused of co-operating with drug trafficking.

He began an unprecedented diplomatic operation to free El Padrí, something unheard of and not enjoyed, for example, García Luna. Mexico complained of sovereign interference by not being aware of the investigation or arrest, even with diplomatic cable in the middle. The first court hearings were held, it was ensured that there was clear evidence … And suddenly, a month later and without anyone expecting it, the US prosecution surprised by removing all charges against the general for ” sensitive and important foreign policy considerations “, all of years of gathering information about the ex-military’s tricks with drug traffickers.

In less than a day Cienfuegos went from being the most important high-ranking official in the face of drug trafficking charges to being a free man in Mexican territory. In the background sounded rumors of threats to fulminate anti-drug cooperation.

AMLO’s promise of government was that it would be investigated in Cienfuegos, but all indications are that it will be left on wet paper. The Mexican government itself recently reported that it was classifying material related to the general for five years. The Wall Street Journal, citing sources from both countries, added that the evidence against Cienfuegos was not “solid.”

The option for the general to end up without facing justice, neither on either side of the border, earns points.

Salvador Cienfuegos, former Secretary of Defense, was arrested in late October; the US prosecution withdrew the charges. Photo: ARXIU AP

Act 3: César Duarte Jáquez. The one who waits

In early July, just as Andrés Manuel López Obrador was entering the White House with his entourage, which was his first and only international trip, the rumor of César Duarte’s arrest in Miami began to ring. Jáquez, former PRI governor of Chihuahua (2010-2016) accused in Mexico of embezzlement and other crimes.

Suspicions of exchanging “gifts” were feasible: Trump softening his profile with Latino voters and receiving something akin to a Mexican president’s blessing, AMLO scoring the point of arresting another politician accused of corruption. Everyone denied it.

Duarte, like all defendants, first tried to avoid his trial by asking for bail, which he was denied. Shortly afterwards the fight began to prove that the extradition request was not valid enough to be executed and should therefore be dismissed as the offenses would have expired.

Awaiting resolutions and motions yet to be presented this New Year, Duarte Jáquez ran out of options one by one. What appears to be the final extradition hearing, unless delayed again by the pandemic situation or any other need on the case, will be held in mid-January.

César Duarte Jáquez, former PRI governor of Chihuahua, was arrested for extradition purposes. Photo: EL UNIVERSAL ARCHIVE

Epilogue: the children of the cartel

That the largest court cases of Mexicans in the United States are starring high-ranking public officials does not mean there is a respite for Mexican cartel leaders who are being persecuted by American Union authorities. This 2020, in fact, has been a “bad year” for the children of the great bosses.

After the heat of the failed apprehension of Ovid Guzmán, son of the Chapo, all the pressure fell in the heirs of other great names of the Mexican drug traffic.

At the beginning of the year it was the turn of Rubén Oseguera González, Menchito, the son of the leader of the Jalisco Cartel Nueva Generación Nemesio Oseguera Cervantes, Mencho, one of the most wanted criminals by all American agencies and Chicago’s number one public enemy.

Menchito dodged extradition for nearly five years, but in February of that year he landed in Washington DC to face charges of drug trafficking and use of firearms to commit crimes. In his first appearance before the judge, in which he pleaded not guilty, he was accompanied on the bench by the public Jessica Oseguera González, his sister.

Few expected that, on departure, the Black would be arrested for her dealings with companies linked to her father’s cartel. He was about to be released on bail, but in the end it was not so. His trial already has a start date: March 22nd.

The other big drug trafficking gang that has spent a 2020 behind bars is Ismael Zambada Imperial, Mayito Gros. In late 2019 he was extradited to the United States; beyond the initial hearing, in which he pleaded not guilty to two drug offenses, May’s son has not been released from prison pending trial, in part because his defense is reviewing the massive evidence against him. (Blackberry documents and messages intercepted) and the coronavirus pandemic, which has frozen court hearings in San Diego, California since mid-April.

In addition, the United States has renewed its interest in Rafael Car Quintero, a priority goal of the DEA since 2018 but on which it is trying to circle even more, after putting on the blacklist what is considered one of its main partners and ironworkers.