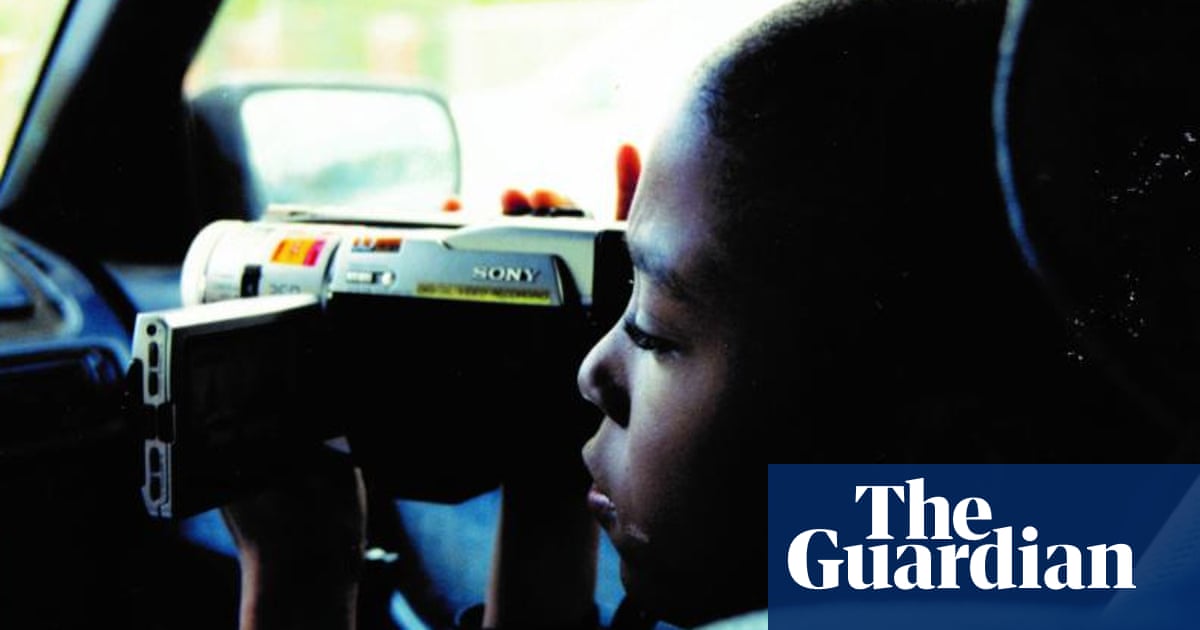

JoIn 1999, Davy Rothbart was 23 years old and was staying on a friend’s couch in southeast DC, a few blocks from a basketball court, where he befriended Akil “Smurf” Sanford, 15. years, and of his early nine-year-old brother. , Emmanuel. Rothbart, an aspiring filmmaker, had a small handheld video camera, to which the little brother was immediately taken; the two were messing with the amateur device, considering their everyday gaze. “We learned to use it together,” Rothbart told the Guardian: walking around the neighborhood, interviewing people on the street, making dolls with night vision, letting their curiosity guide the target.

The resulting videos form 17 blocks, distilling 1,000 hours of filming over 20 years into a poignant, sometimes heartbreaking, surprisingly generous documentary about an American black family facing drug addiction, cycles of gun violence. fire and the passage of gifts and waste of time. While the film doesn’t shy away from political comments: the title is a one-time reference to the distance between Sanford’s underprivileged, largely segregated neighborhood and the Capitol, which turns a blind eye, the project unfolded from something smaller and more intangible: mutual friendship. , and an interest in preserving the things of cinema. Rothbart began leaving the camera at the Sanfords, so that Emmanuel and Smurfs could film in his time, often capturing his sister Denice and mother Cheryl. “It was really an organic thing,” Rothbart said.

The first third of 17 blocks, filmed in 1999 and the early 2000s, is piqued with curiosity, especially thanks to Emmanuel, who showed a special affinity for making films and filling the screen with his lush smile (describes your favorite topic as “talking on the phone,” for example, adds “and I’m a superstar”). “Even at age nine, Emmanuel had a poetic eye,” Rothbart said. “He was throwing out the window like a branch swaying in the wind or shooting two people (their voices couldn’t be heard), holding a conversation on the street and turning around. He just had a very interesting visual sense.”

Many of Emmanuel’s videos focused on his mother, Cheryl, who remembers appreciating the production of amateur films not only retaining memories as an opportunity to shine. “At the time they were just home videos,” he told The Guardian. Sanford grew up in the middle class, the son of a DC government worker, and dreamed of becoming an actor, “so for me it was, ‘I’m a star of my own movie’ … I thought it was Marilyn Monroe anyway. “

Sanford worries about the awkward, raw moments captured by Emmanuel at the time: a physical fight with her boyfriend, moments when she has passed on the couch in an ongoing fight against drug addiction, calling her father to ask for it. money. narrow houses in southeast DC where the family lives. “The past cannot be changed, the past is the past. It’s relevant to me so far, “Sanford said of allowing viewers to enter this time of their lives.” My life experience is similar to that of many single parents … I don’t mind having it on screen. “My life is my life. This is what has happened to me. Maybe someone who is having a hard time in life with some of the experiences I had, maybe they will get something out of it.”

The film is divided into a horrific act of gun violence: on New Year’s Eve 2009, Emmanuel was shot dead at home (no arrests were ever made). The massacre and devastation are captured by the Sanfords’ resounding camera, which goes through a decade of mourning, activism, reconciliation, forgiveness and learns to speak of an unimaginable loss, through the growth of gun violence and protests. of black life. Rothbart had remained close to the family over the years, spending vacations together and, following Emmanuel’s death, in grief (the relationship and respect between Sanford and Rothbart were clear in a joint interview).

“We felt very determined to have to tell Emmanuel’s story and we realized it wasn’t just Emmanuel’s story, but the whole family’s story,” Rothbart said. The cameras continued to roll after 2009, as “it was something we were in a ritual to do when we were together.” In the last third of the film, in 2016, Denice’s son, Justin, puzzling, curious, who does it on camera, is the same age as Emmanuel was when Rothbart met him on the basketball court.

The project of the free-flyer film, and the large amount of home video and low-participation treasures he left behind, took on a new purpose after Emmanuel’s death. “I wanted memories of him, period,” Sanford said. The collection of videos before and after his passing, distributed over a thousand hours by video editor Jennifer Tiexiera, offers viewers the opportunity to learn about Emmanuel as something more than a grim statistic of gun violence of fire often armed by American policymakers and experts in black communities. “You may not have known him, but here’s who I lost, look what I lost,” Sanford said of the film. “This is just a story and, although there are many, it is the same story.

“This movie is real life,” he said. “It’s not like what they see on television, because television is imitation. That’s real life, it happens, it’s pretty normal for many of us. “

“It’s so wonderful and brave for them to share their story in such an intimate way,” said Rothbart, who credited Sanford’s firmness in recognizing the power of simply observing his complicated, metastatic and incredible pain. “Even then, [she] he knew this would have value someday, “he said. After losing friends and children of friends due to armed violence,” he knew how challenging and painful “the weeks immediately following Emmanuel’s death would be. But he said, “People need to see this,” Rothbart recalled, “People need to know what it’s like to have something like this happen in their family. We have to film it all.”

“People could meet him as a boy and then recognize the boy who got lost here.”

Time beats and the last section of the film watches the Sanfords, now adults, growing into the future: Cheryl fights for sobriety; Smurf, a compassionate judge too rare saved time in prison, finding stable work in a deli and playing with his children; Denice training to be a security officer. Out of frame, Rothbart and Cheryl Sanford look to a more secure future; the filmmakers have partnered with Everytown for Gun Safety and Black Lives Matter for the screenings, and together they embarked on a program, from Washington to Washington, that takes young people from DC neighborhoods on field trips.

“The title of the film is almost a challenge,” Rothbart said. “The family lives on 17 islands in the United States Capitol, and that’s what’s happening in this neighborhood. It’s kind of a challenge for people in power, and really for any audience member, to ask themselves: what can I do to try to create more opportunities for people living in neighborhoods like this and change some of the results?

“Gun violence is a symptom, not a cause, of other issues, of other challenges facing these neighborhoods that are not being adequately met,” he added. (“Correct,” Sanford said.)

Seventeen blocks ends with a tribute to those lost to armed violence in DC during the ten years following Emmanuel’s assassination: a list, with more than 1,200 names in tiny sources, that continues for pages, too long. “Each of those names could be their own documentary,” Rothbart said. “And this is a family that is in grief, even if it misses its loved one.”