More than a year after a “mysterious pneumonia” sickened workers at a seafood market in China, scientists are still gathering clues as to where SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes the COVID-19.

“It’s critical to understand where this virus comes from, so we can understand how to prevent future outbreaks in the future,” said Anne Rimoin, a UCLA infectious disease epidemiologist.

Research into the origins of the virus is crucial for public health and science reasons, but it has also sparked tensions between world powers, especially the United States and China, whose leaders have been accused of lacking transparency and xenophobia. during the pandemic.

“It’s not about pointing with your fingers, it’s about understanding it, so we know how to do it better in the future,” Rimoin said.

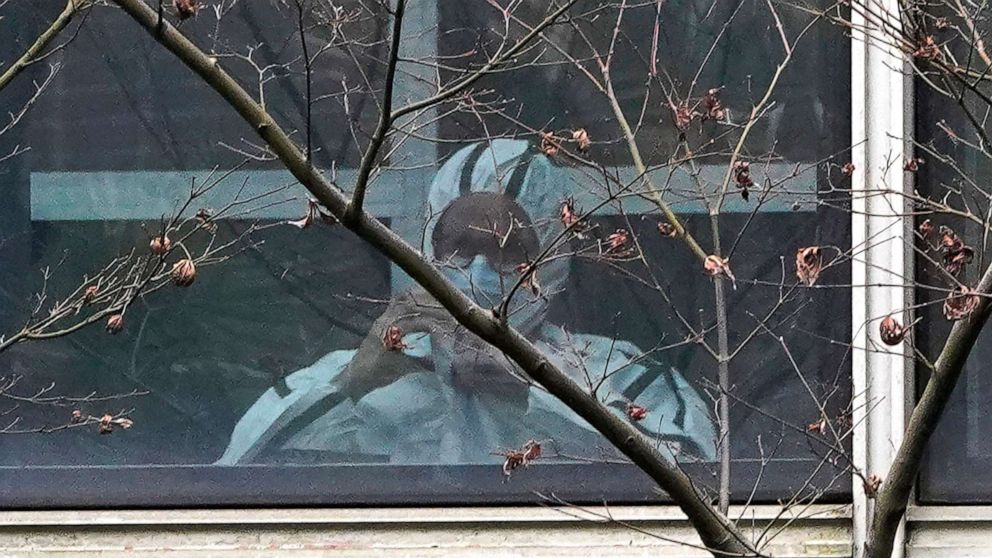

To this end, on January 14, 2021, the World Health Organization deployed a group of 17 international experts to Wuhan to work with Chinese scientists on an in-depth investigation into the origins of the virus.

Scientists have long said that SARS-CoV-2 has zoonotic origins, meaning it probably jumped from animals to humans when humans came in contact with an animal infected with the virus. According to Rimoin, this contact could include handling the infected animal, feeding it or preparing it for the market.

However, experts did not know exactly how the virus had entered people and reaching a definitive conclusion about the origins of SARS-CoV-2 could take years. Nor do they know where or when the virus was first introduced to humans, and several studies suggest it may have been present elsewhere in the world (perhaps circulating at low levels) before the major outbreak in Wuhan, China.

“Try to reconstruct the events of a year and a half ago with incomplete sampling and data,” Dr. W. Ian Lipkin, director of the Center for Infection and Immunity at Columbia University, told ABC News. “Maybe we’ll never know exactly what happened.”

If previous investigations of infectious diseases are any clue, the origins of the virus could be shrouded in mystery. The best comparison is the 2003 SARS outbreak, which was caused by a close cousin of the virus that causes COVID-19 and eventually went back to a single population of horseshoe bats.

But this search took more than five years. “I think they were very lucky,” Vincent Racaniello, a professor of microbiology and immunology at Columbia University’s College of Physicians and Surgeons, said about the SARS research. “We have not yet found the origin of the Ebola virus outbreaks after many years of research,” he added. “It’s not easy.”

The joint WHO-China report is considered a first step in what is likely to be a multi-year investigation that published its findings last week. But the report itself has been embroiled in controversy. Following his release, the United States and 13 other countries raised concerns about the report in a joint statement, arguing that the international investigation “was significantly delayed and had no access to original and complete data and samples.”

But many experts say the report, while imperfect, is an important first step.

The researchers explored four main theories about how the virus was poured into humans, classifying them in order of probability, from “very likely” to “extremely unlikely.”

Intermediate host theory: This theory proposes that the virus was transmitted from an original animal host to an intermediate host, such as minks, pangolins, rabbits, raccoon dogs, domestic cats, civets, or ferrets, and then humans were directly infected. through live contact with the second animal.

Conclusion of the WHO-China research: “likely to very likely”

The theory of zoonotic overflow: Zoonotic overflow theory suggests that SARS-CoV-2 was transmitted directly to a human from an animal, most likely a bat. This transmission could have occurred through agriculture, hunting, or any other close contact between humans and animals.

Conclusion of the WHO-China research: “possible to probable”

Frozen food chain theory: The “cold chain” theory suggests that the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 from animals to humans may have occurred through contaminated frozen foods. A frozen food product contaminated with animal waste containing SARS-CoV-2 could have transferred the virus to humans without any direct human-animal contact.

Conclusion of the WHO-China research: “possible”

The controversial laboratory leak theory is found to be “extremely unlikely”

As part of the research, scientists returned to the Huanan fish and seafood market associated with the first known cluster of cases in Wuhan. They also visited Hubei Provincial Hospital of Integrated Chinese and Western Medicine, where some of the first cases of COVID-19 were treated, and examined viral sequencing data. This viral sequencing showed that different minor variants of SARS-CoV-2 were spreading in Wuhan in December 2020.

“This again suggests that perhaps the virus had been circulating a little longer than people had noticed,” said Dominic Dwyer, an epidemiologist and member of the WHO research team.

Viral sequencing also showed that the Huanan market was probably not the main source of the outbreak. Although many initial cases were market-related, a similar number of cases were associated with other markets, or with no market, the WHO-China report found.

“The market was certainly an amplifier, but it was probably not the real source of the whole outbreak,” Dwyer said.

Previous genomic sequencing showed that the virus had natural origins and the WHO-China team classified the laboratory leak theory as “extremely unlikely.”

But Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, WHO’s director general, said he did not believe the team’s assessment of the theory was sufficiently extensive.

More data and studies will be needed to reach stronger conclusions, Tedros told a news conference about the report’s findings, noting that he was willing to deploy additional missions with specialized experts to do so.

“Science can’t rule things out like that,” said Peter Daszak, a zoologist and member of the WHO research team, about the theory of laboratory leaks. “Only positive results can be shown, they can’t be shown to be negative. But what we found was that the escape to the lab was extremely unlikely.”

The report found that the most likely route was the first theory, according to which the virus passed from a bat to an intermediate animal and then to humans. According to Daszak, the next steps for the investigation could include tracing the first cases of the virus; investigate market suppliers to find unusual peaks in antibodies; and examine locations with concentrations of animals that we know are susceptible to SARS-CoV-2.

Rimoin hopes the pandemic has shown that disease surveillance is key to preventing future outbreaks, not just reacting to them. As population growth and climate change push humans into animal habitats, “we will see more viruses jumping from animals to humans and we will see more disease emergency events,” Rimoin said.

“An infection anywhere is potentially an infection everywhere,” he said.

Sasha Pezenik, Sony Salzman and Eric Silberman of ABC News contributed to this report.

Eric Silberman, MD, a resident physician in internal medicine at Northwestern Memorial Hospital, is a contributor to the ABC News Medical Unit.