Two programs, one that provides assistance for self-employed and contract workers, and the other for people who have been unemployed for more than six months, will expire on Monday. As a result, 8.9 million people will lose these benefits weekly, according to an estimate by Oxford Economics.

An additional 2.1 million people will lose a federal unemployment payment of $ 300 a week, which also expires Monday. These beneficiaries, however, will continue to receive state unemployment benefits.

The cuts come as employers have been constantly hiring and firing fewer workers. The number of people applying for unemployment benefits fell from 14,000 last week to 340,000, the Labor Department said on Thursday, to the lowest level since the pandemic occurred in March last year.

However, the number of people who will lose financial aid from next week is much higher than the previous reductions in extended unemployment benefits. After the Great Recession of 2008-2009, for example, when unemployment benefits were extended to 99 weeks, this extension lasted until 2013. When this benefit program finally ended, only 1.3 million people they were still receiving help.

The current expanded unemployment assistance programs were created under financial bailout legislation that was enacted after the pandemic erupted and that President Joe Biden extended last March. Lawmakers generally hoped that by September, with the vaccination of more Americans and the intensification of hiring employers, the pandemic would fade and the economy would fully recover.

As the economy picks up, economists worry that the delta variant could slow recruitment and growth. When the government releases its August jobs report on Friday, some analysts expect it to show a slowdown in hiring.

Reducing unemployment checks by millions next week will abruptly eliminate a vital source of income for many.

“We were a thriving middle-class family 18 months ago,” said Chenon Hussey of West Bend, Wisconsin. “Let’s fall off the map” when federal benefits end.

Hussey, 42, who works part-time for a county government, is trying to revive a small motivational business that was shattered by the pandemic. Her husband, a master welder, has been fired three times during the health crisis.

Federal benefits, she said, have been “the bridge of absolute poverty for us.” Without them, Hussey said, their monthly income would drop by $ 2,800. They will not be able to afford the intensive care their daughter, who has developmental disabilities, needs. Maybe they’ll have to move her to a group home, “which is what we never wanted for her”.

Their cars are paid off, but the mortgage is still a struggle.

“It will take us a while to get through it,” he said. “We are positive in the fact that we are both willing to do what we have to do.”

Twenty-five states have already completed the $ 300 weekly supplement and nearly all of them have also stopped the two federal emergency programs, ending payments to about 3.5 million people, according to Oxford Economics. These first cuts came after some businesses complained in the spring and summer of not finding enough people to hire.

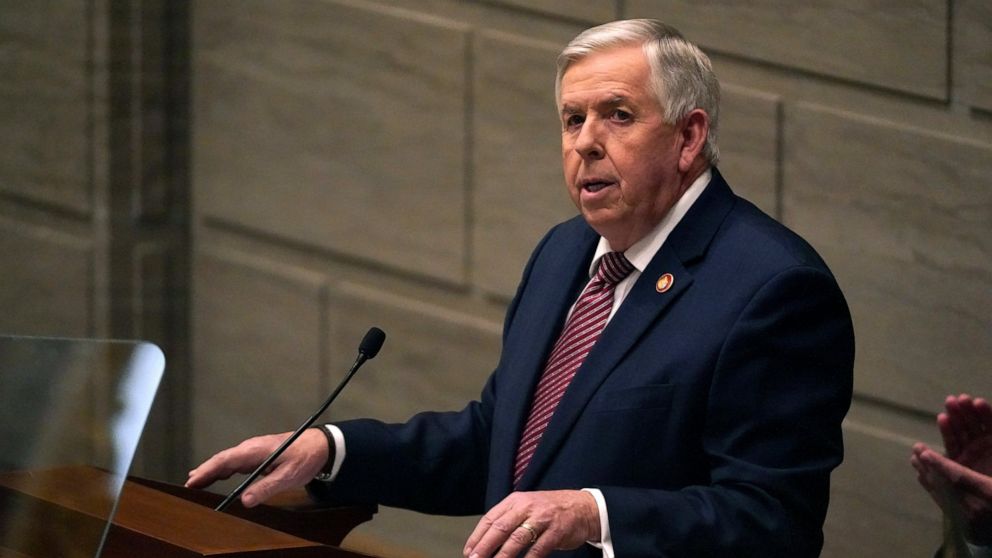

Nearly all 25 states are run by Republican governors – with the exception of Louisiana – and most said the $ 300 a week in additional federal aid deterred the unemployed from working. Published job vacancies (a record 10.1 million in June) have risen faster than candidates who have prepared to fill them.

However, research has shown that the first cuts in federal unemployment benefits have only led to a small increase, at most, in hiring. A study by Kyle Coombs, an economist at Columbia University, and Arindrajit Dube, an economist at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, found that in states that maintained federal benefit programs, 22% of people receiving benefits in in April they had found work in late July. In the states with cutting aid, this figure was almost 26%, a modest increase.

Other research has found an even smaller impact: in a report last week, JP Morgan economists Peter McCrory and Daniel Silver found a “zero correlation” between employment growth and state decisions to withdraw employment. federal unemployment benefits, at least so far. They warned that the loss of income due to a cut in unemployment controls “could lead to the loss of jobs, potentially offsetting the gains” of encouraging more people to return to work.

Most economists cite other factors that have hampered the work of companies because of the pay they offer: many of the unemployed do not want to work in service industries such as restaurants and hotels, for fear of hiring COVID 19. In addition, many women have left the job market to care for children and have had difficulty finding or allowing themselves to care for children.

Andrew Stettner, a senior member of the Century Foundation, a think tank, estimates that the expiration of benefit programs will reduce aid payments by $ 5 billion a week, which is likely to weaken spending.

“We’re tired of the pandemic, but that doesn’t mean we give up taking the steps we need to keep people afloat,” Stettner said.