Press release

Monday, September 6, 2021

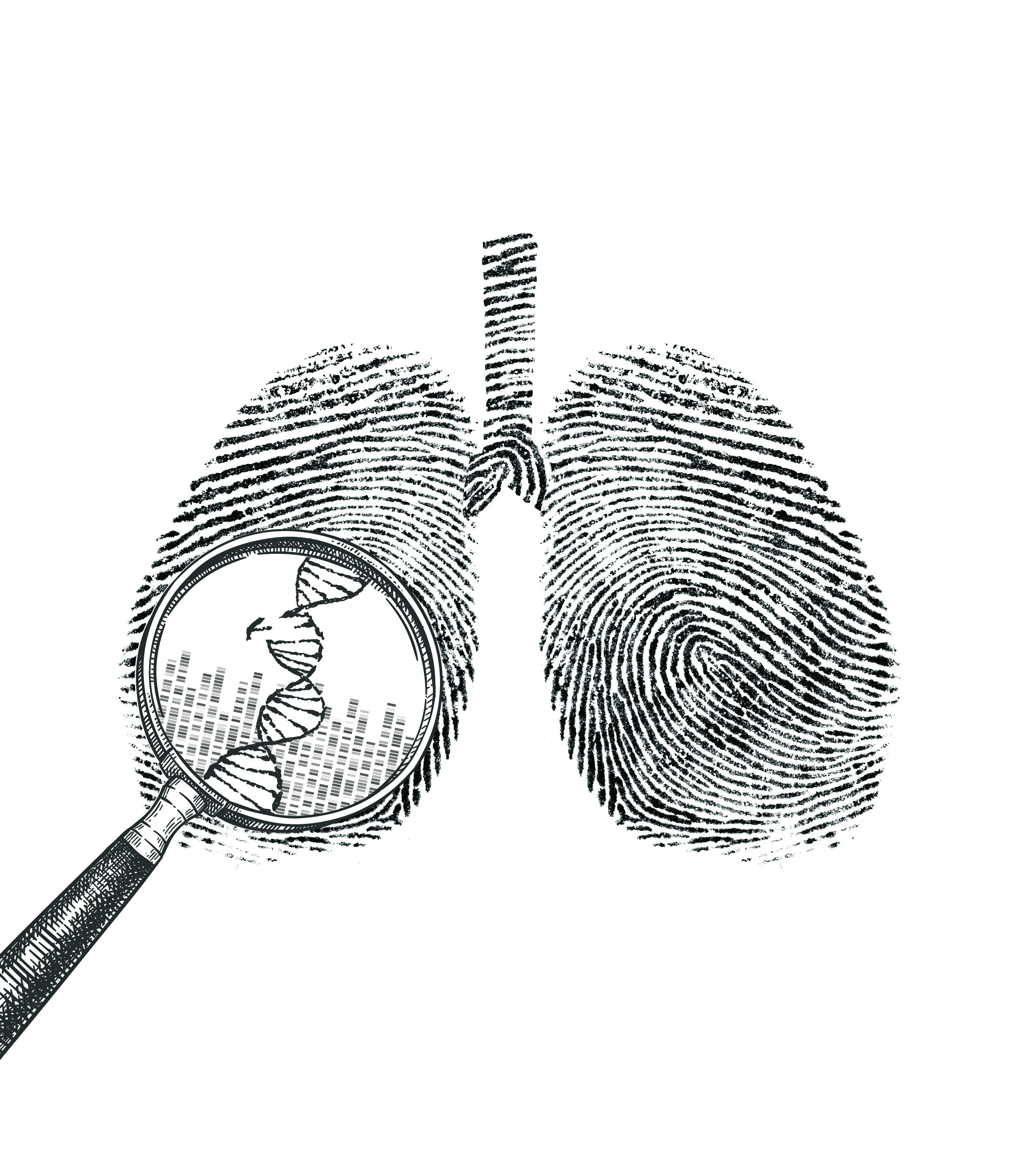

A genomic analysis of lung cancer in people with no history of smoking has shown that most of these tumors arise from the accumulation of mutations caused by natural processes in the body. This study was conducted by an international team led by researchers from the National Cancer Institute (NCI), which is part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and describes for the first time three molecular subtypes of lung cancer in people who never they smoked.

These ideas will help unravel the mystery of how lung cancer arises in people who have no history of smoking and can guide the development of more accurate clinical treatments. The findings were published on September 6, 2021 a Genetics of nature.

“What we’re seeing is that there are different subtypes of lung cancer in smokers than ever that have different molecular characteristics and evolutionary processes,” said epidemiologist Maria Teresa Landi, MD, Ph.D., of the branch of integrative tumor epidemiology in the NCI division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, which led the study, which was conducted in collaboration with researchers from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, another part of NIH and other institutions. “In the future we could have different treatments based on these subtypes.”

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide. Every year, more than 2 million people worldwide are diagnosed with the disease. Most people who develop lung cancer have a history of smoking tobacco, but 10% to 20% of people who develop lung cancer have never smoked. Lung cancer in smokers never occurs more frequently in women and at earlier ages than lung cancer in smokers.

Environmental risk factors, such as exposure to second-hand tobacco smoke, radon, air pollution and asbestos, or having had previous lung disease, may account for some lung cancers among which never they smoke, but scientists still don’t know what causes most of these cancers. .

In this extensive epidemiological study, researchers used genome-wide sequencing to characterize genomic changes in tumor tissue and matched the normal tissue of 232 smokers ever, mostly of European descent, who had been diagnosed with cancer. of non-small cell lung. Tumors included 189 adenocarcinomas (the most common type of lung cancer), 36 carcinoids, and seven other tumors of various types. Patients had not yet undergone treatment for their cancer.

The researchers combed the tumor genomes to obtain mutational signatures, which are patterns of mutations associated with specific mutational processes, such as damage caused by natural activities in the body (e.g., poor DNA repair or oxidative stress) or by exposure to carcinogens. Mutational signatures act as an archive of activities of a tumor that led to the accumulation of mutations, providing clues as to what caused the development of cancer. There is now a catalog of known mutational signatures, although some signatures have no known cause. In this study, the researchers found that most never-smoking tumor genomes bore mutational signatures associated with damage from endogenous processes, that is, natural processes that occur inside the body.

As expected, since the study was limited to never smoking, the researchers found no mutational signatures that had previously been associated with direct exposure to smoking. Nor did they find these signatures among the 62 patients who had been exposed to second-hand tobacco smoke. However, Dr. Landi warned that the sample size was small and that the level of exposure was very variable.

“We need a larger sample size with detailed information on exposure to really study the impact of second-hand tobacco smoking on the development of lung cancer in smokers,” Dr. Landi said.

Genomic analyzes also revealed three new subtypes of never-smoking lung cancer, to which researchers assigned musical names based on the level of “noise” (i.e., the number of genomic changes) in tumors. The predominant “piano” subtype had the lowest mutations; it appeared to be associated with the activation of progenitor cells, which are involved in the creation of new cells. This tumor subtype grows extremely slowly, over many years, and is difficult to treat because it can have many different mutations. The “mezzo-forte” subtype had specific chromosomal changes as well as mutations in the growth factor receptor gene EGFR, which is usually altered in lung cancer and has a faster tumor growth. The “strong” subtype featured twice the entire genome, a genomic change often seen in lung cancers in smokers. This tumor subtype also grows rapidly.

“We are beginning to distinguish subtypes that may have different approaches to prevention and treatment,” Dr. Landi said. For example, the slow-growing piano subtype could give clinicians a window of opportunity to detect these tumors earlier when they are less difficult to treat. In contrast, the mezzo-forte and forte subtypes have only a few major motor mutations, suggesting that these tumors could be identified by a single biopsy and could benefit from specific treatments, he said.

A future direction of this research will be to study people from different ethnic backgrounds and geographic locations, and whose history of exposure to lung cancer risk factors is well described.

“We are at the beginning of understanding how these tumors evolve,” Dr. Landi said. This analysis shows that there is heterogeneity or diversity in lung cancers in never-smokers.

Stephen J. Chanock, MD, director of NCI’s Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, noted, “We hope this detective-style research into genomic tumor features will unlock new avenues of discovery for various types of cancer. “.

The study was conducted by NCI’s Intramural Research Program and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences.

About the National Cancer Institute (NCI): NCI leads the efforts of the National Cancer Program and NIH to drastically reduce the prevalence of cancer and improve the lives of cancer patients and their families, through research into cancer prevention and biology, the development of new interventions, and the training and mentoring of new researchers. For more information on cancer, visit the NCI website at cancer.gov or call the NCI contact center, the Cancer Information Service, at 1-800-4-CANCER (1-800-422- 6237).

Regarding the National Institutes of Health (NIH):

NIH, the country’s medical research agency, includes 27 institutes and centers and is a component of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. NIH is the leading federal agency that conducts and supports basic, clinical, and translational medical research and investigates the causes, treatments, and cures for common and rare diseases. For more information about NIH and its programs, visit www.nih.gov.

NIH … Turning discovery into health®