Most people who develop lung cancer have a history of smoking. However, up to a quarter of all cases, the patient has never been enlightened in their lifetime.

An extensive new study on these so-called never-smokers has identified three unique subtypes of lung cancer that appear to arise without an apparent environmental trigger, such as smoke, asbestos, or air pollution.

“What we’re seeing is that there are different subtypes of lung cancer in ever-smokers that have different molecular characteristics and evolutionary processes,” explains epidemiologist Maria Teresa Landi of the U.S. National Institutes of Health.

“In the future we could have different treatments based on these subtypes.”

Today, smoking has caused a global lung cancer epidemic (with 2 million diagnoses occurring each year), although it is not yet known how this disease arises in those who have never smoked.

New research has now provided several clues as to how these non-smoking cancers originate.

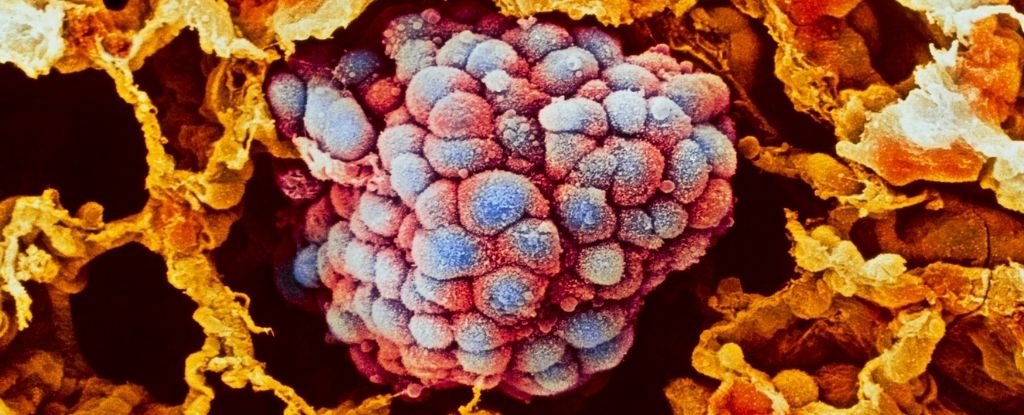

When scientists sequenced the genomes of frozen tumor tissue, sampled from 232 never-diagnosed smokers of non-small cell lung cancer (by far the most common of the two main types of lung cancer), they observed several mutational signatures that they were not apparent in normal lung tissue.

These genetic changes are slightly different from what happens when tobacco smoke causes cancer, suggesting that an alternative form of lung damage may be to blame, which can occur in the person’s body, such as a faulty repair of DNA or oxidative stress.

Even those 62 smokers who had never been exposed to second-hand smoke showed signatures similar to those of others who never smoked in tumor tissue. This indicates that their disease is the product of internal body changes and not of environmental stressors, although the sample size in this case is relatively small.

“We need a larger sample size with detailed information on exposure to really study the impact of second-hand tobacco smoking on the development of lung cancer in smokers than ever before,” Landi admits.

Patients in this study were also mostly of European descent, which means that future research will need to improve the diversity of its participants.

That said, the authors have identified three new subtypes of lung cancer in their cohort.

The first and most common subtype they have named piano (from the Italian musical term for “soft and quiet”), because it shows the few genomic mutations. This subtype of lung cancer is associated with progenitor cells, which help create new cells in the lung. It also grows slowly, which means it can be detected ten years in advance.

The second subtype is not so easily detected and grows very rapidly. He has been appointed mig fort because their genomic mutations are a little stronger and stronger. This type of lung cancer appears to be related to mutations in the growth factor receptor gene known as EGFR.

It is called the final subtype of non-smoking lung cancer fort, the “strongest” of the lot. It presents with a mutation known as duplication of the entire genome, which is also seen in smokers ’lung cancers.

However, their genomic signatures do not strongly coincide with tobacco smokers, even when patients had experienced second-hand smoke.

“We’re at the beginning of understanding how these tumors evolve,” Landi says. “This analysis shows that there is heterogeneity or diversity in lung cancers in never-smokers.”

Knowing how natural lung cancers arise and how they differ from smoking-induced cancers is critical if we are to treat them properly. Scientists are already testing treatments for mutations in the EGFR gene and could one day be effective for those with the gene. mig fort natural lung cancer subtype.

He piano the subtype, on the other hand, will probably be a little more difficult to treat, as their genetic mutations appear to have multiple motors, making them more difficult to target with drugs.

However, the authors point out that if we can find a pharmaceutical that interrupts the signals to the progenitor cells of the lungs, it could help stop the growth of piano tumors.

The authors hope their research will continue to inspire research into lung cancer drugs in the future, especially for those who have never blown a cigarette in their lifetime.

The study was published in Genetics of nature.