An extensive new study has provided solid evidence that people with brown fats in the body are less likely to suffer from a number of health conditions.

“For the first time, it reveals a link with a lower risk of certain conditions,” says one of the researchers, Rockefeller University Hospital physician Paul Cohen.

“These findings make us more confident about the potential to target brown fat for therapeutic benefits.”

Brown fat or brown adipose tissue (BAT) is particularly common in mammals and newborns in hibernation. BAT helps mammals regulate temperature: when we are very cold, the large amounts of mitochondria found in this type of fatty tissue support energy and produce heat. In fact, iron-rich mitochondria are what give brown fat its characteristic color.

It wasn’t until 2009 that scientists discovered that some adult humans also had brown fats on their bodies, usually on their necks and shoulders.

There have been many studies on mice on the benefit of having brown fat, but in humans the research has been more turbulent until recently. Having brown fat seems to improve a person’s metabolism and can even help them lose weight (although it’s probably not that simple).

“The natural question everyone has is,‘ What can I do to get more brown fat? “Says Cohen.

“We don’t have a good answer to that yet, but it will be an exciting space for scientists to explore in the coming years.”

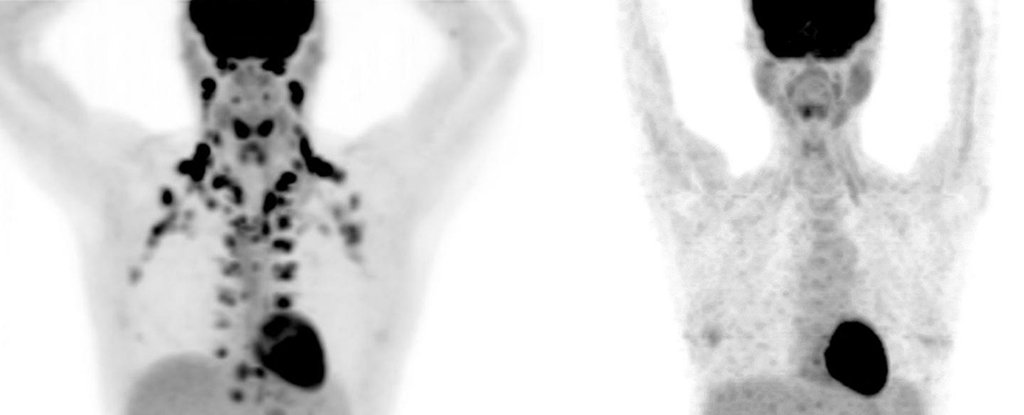

Observing a large data set of 52,487 participants undergoing PET / CT scans to assess cancer, the team found evidence of brown fat in just under 10 percent of cases (5,070 people).

The researchers think this could be an underestimation due to the conditions in which the participants were subjected: before the explorations they were told to avoid exposure to cold, exercise and caffeine, all of which were related to activity of brown fats.

About 4.6 percent of people with brown fat also had type 2 diabetes, while that number was 9.5 percent in the “no brown fat” group. A similar result was observed in abnormal cholesterol results: 18.9 percent of people with brown fat had abnormal cholesterol, compared with 22.2 percent of people who did not have brown fat.

Hypertension, congestive heart failure, and coronary artery disease also saw small positive differences in the brown vs. non-brown fat groups.

“These findings were supported by improved levels of high-density blood glucose, triglycerides and lipoproteins,” the team writes in its new article.

While the numbers here are exciting, there is still no evidence that brown fat makes you immune to any of these conditions, but there is a link to a reduced risk that is worth exploring.

What was really interesting was that brown fat was especially protective in those who were obese. Those obese patients who had brown fat had a similar prevalence of these metabolic and heart diseases than non-obese people.

“They seem to be protected from the harmful effects of white fat,” Cohen says.

“Overall, our findings highlight a potential role of BAT in promoting cardiometabolic health,” the researchers point to in their work.

It is important to note that the data the researchers worked with came from cancer assessments at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, meaning that it is not a representative sample of the general population.

However, the study has taken a fascinating new look at the role of brown fat in the human body and hopefully will lead to more discoveries in the future.

“We’re considering the possibility that brown fatty tissues do more than consume glucose and burn calories, and maybe actually participate in hormonal signaling to other organs,” Cohen says.

The research has been published in Nature medicine.