An influential current system in the Atlantic Ocean, which plays a vital role in redistributing heat throughout our planet’s climate system, is now moving more slowly than in at least 1,600 years. This is the conclusion of a new study published in the journal Nature Geoscience by some of the world’s leading experts in this field.

Scientists believe that part of this slowdown is directly related to our warming climate ice melting alters the balance in northern waters. Its impact can be seen in storms, heat waves and sea level rise. And it reinforces the concern that if humans are not able to limit warming, the system could reach a turning point, throwing global climate patterns into disarray.

The Gulf Stream along the east coast of the United States is an integral part of this system, known as the South Atlantic Vault Circulation or AMOC. He became famous in the 2004 film “The Day After Tomorrow,” in which the ocean current comes to an abrupt halt, causing huge killer storms to revolve around the world, like a supercharged tornado in Los Angeles and a wall. of water that crushes New York.

As with many science fiction films, the plot is based on a real concept, but the impacts are taken to a dramatic extreme. Fortunately, an abrupt shutdown of the current is not expected soon, if ever. Even if the current were to stop – and this is hotly debated – the result would not be instantaneous storms greater than life, but over the years and decades the impacts would certainly be devastating for our planet.

Recent research has shown that circulation has slowed by at least 15% since 1950. Scientists in the new study say the weakening of the current is “unprecedented in the past millennium.”

Since everything is connected, the slowdown is already undoubtedly having an impact on terrestrial systems and, by the end of the century, it is estimated that circulation can decrease by between 34% and 45% if we continue to warm the planet. Scientists fear that this type of slowdown will put us dangerously close to turning points.

Importance of the global ocean carrier

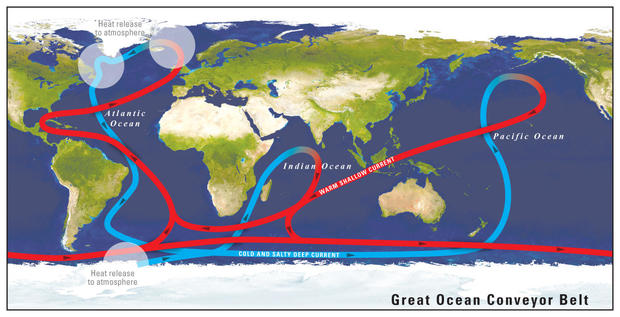

Because the equator receives much more direct sunlight than colder poles, heat builds up in the tropics. In an effort to achieve equilibrium, the Earth sends this heat northward from the tropics and sends cold southward from the poles. This is what causes the wind to blow and storms to form.

Most of this heat is redistributed by the atmosphere. But the rest moves more slowly across the oceans in what is called the Global Ocean Conveyor Belt, a global system of currents that connects the world’s oceans, moving in all different directions horizontally and vertically.

NOAA

Over years of scientific research, it has become clear that the Atlantic part of the conveyor belt, the AMOC, is the engine that drives its operation. The water moves 100 times the flow of the Amazon River. This is how it works.

A narrow band of warm, salt water in the tropics near Florida, called the Gulf Stream, is carried north near the surface to the North Atlantic. When it reaches the Greenland region, it cools enough to become denser and heavier than the surrounding waters, at which point it sinks. This cold water is then carried south in deep water streams.

Through intermediate records such as ocean sediment nuclei, which allow scientists to reconstruct the distant past millions of years ago, scientists know that this current has the ability to slow down and stop, and when it does, the climate in the northern hemisphere can change rapidly.

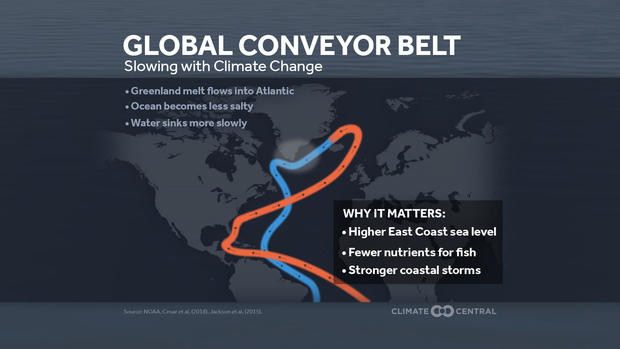

An important mechanism over the centuries, which acts as a kind of lever that controls the speed of the AMOC, is the melting of glacial ice and the consequent entry of fresh water into the North Atlantic. This is because fresh water is less salty and therefore less dense than seawater, and does not sink so easily. Too much fresh water means that the conveyor belt loses the sinking part of the engine and therefore loses its momentum.

This is what scientists believe is happening now like ice in the Arctic, in places like Greenland, it melts at an accelerated rate due to human-induced climate change.

Central climate

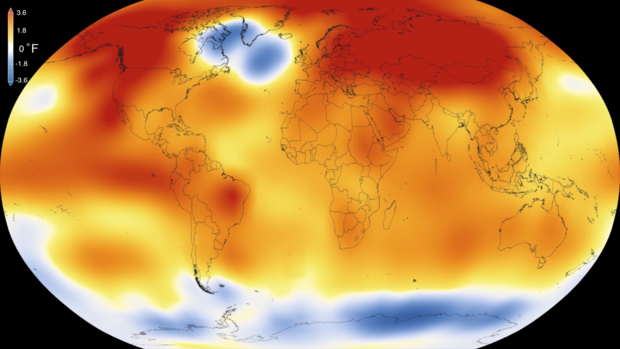

Recently, scientists have noticed a cold drop, also known as the North Atlantic warming hole, in a stretch of the North Atlantic south of Greenland, one of the only places that really cools on the planet.

The fact that climate models predicted it provides more evidence indicating Greenland’s excess ice melting, more rainfall, and the consequent slowdown in heat transport from the tropics to the north.

NASA

In order to determine the extent to which the recent slowdown in the AMOC is unprecedented, the research team collected replacement data extracted primarily from nature archives such as ocean sediments and ice cores, which go back further. of 1,000 years. This helped them reconstruct the history of the AMOC flow.

The team used a combination of three different types of data to obtain information about the history of ocean currents: temperature patterns in the Atlantic Ocean, properties of groundwater mass, and sizes of deep-water sediment grains. , dating back 1,600 years.

Although each individual piece of proxy data is not a perfect representation of the evolution of AMOC, the combination of these revealed a robust picture of the flipping circulation, according to the lead author of the paper, Dr. Levke Caesar, climate physicist at the University of Maynooth in Ireland. .

“The results of the study suggest that it has been relatively stable until the late 19th century,” explains Stefan Rahmstorf, of the Potsdam Climate Impact Research Institute in Germany.

The first significant change in its ocean circulation records occurred in the mid-1800s, after a well-known period of regional cooling called the Little Ice Age, which spanned from 1400 to 1800. During this time, temperatures colder they frequently froze rivers throughout Europe and destroyed crops.

“With the end of the small ice age around 1850, ocean currents began to decline, with a second, more drastic decline since the mid-20th century,” Rahmstorf said. This second decline in recent decades was probably due to global warming caused by burning and emissions of fossil fuel pollution.

Nine of the 11 data sets used in the study showed that the weakening of twentieth-century AMOC is statistically significant, providing evidence that the slowdown is unprecedented in the modern era.

Impact on storms, heat waves and sea level rise

Caesar says this is already reverting to the climate system on both sides of the Atlantic. “As the current slows, more water can accumulate on the east coast of the United States, causing sea levels to rise. [in places like New York and Boston]she explained.

Across the Atlantic in Europe, evidence shows that there are impacts on weather patterns, such as the trail of storms coming out of the Atlantic, as well as heat waves.

“Specifically, the European heat wave of the summer of 2015 has been linked to the record for cold in the North Atlantic that year: this seemingly paradoxical effect occurs because a cold in the North Atlantic promotes a pattern of air pressure driving hot air from the south to Europe, “she said.

According to Caesar, these impacts are likely to continue to worsen as the Earth continues to warm and the AMOC slows further, with more extreme weather events such as a change in the track of winter storms coming out of the Atlantic and potential storms more intense.

CBS News asked Caesar the million-dollar question: if or when the AMOC can reach a turning point leading to a complete closure? She replied, “Well, the problem is we still don’t know how many degrees of global warming has reached the turning point of the AMOC. But the slower it slows down, the more likely we will be.”

He also explained: “The tip does not mean that this happens instantly, but that, due to the feedback mechanisms, the continued slowdown cannot be stopped once the turning point has been passed, even if we have managed to reduce global temperatures again “.

Caesar believes that if we stay below 2 degrees Celsius of global warming, it seems unlikely that the AMOC will tip, but if we reach 3 or 4 degrees of warming, the chances of an increase in descent will increase. Staying below 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) is a goal of the Paris Agreement, which the US has just reunited.

If the turning point is crossed and the AMOC is stopped, the northern hemisphere is likely to cool due to a significant decrease in tropical heat pushed north. But beyond that, Caesar says science still doesn’t know exactly what would happen. “That’s part of the risk.”

But humans have a certain agency in all of this, and the decisions we make now about how quickly we move away from fossil fuels will determine the outcome.

“Whether or not we believe the turning point at the end of this century depends on the amount of warming, that is, the amount of greenhouse gases emitted into the atmosphere,” Caesar explains.