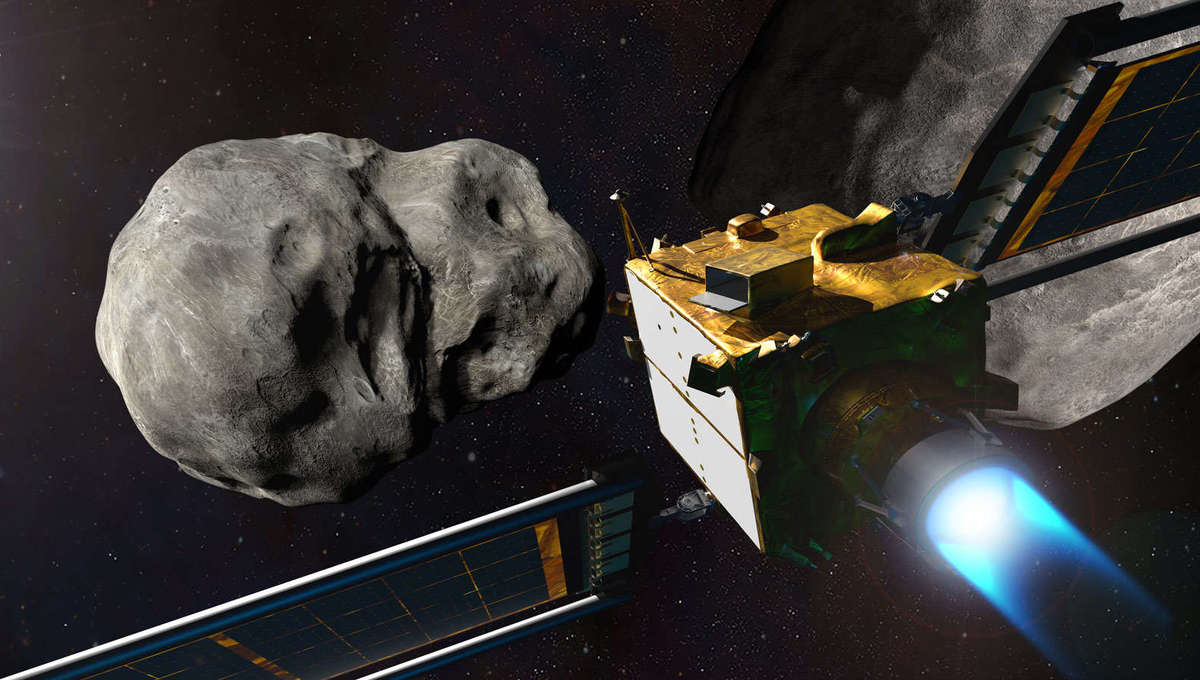

In November 2021, NASA launches a bold mission to test the technology needed in case we ever have to take out a potentially dangerous asteroid from a trajectory that will impact Earth. Called DART, for the double-asteroid redirection test, the 500-kilogram spacecraft will fall against an asteroid’s moon at more than 23,000 kilometers per hour, changing the moon’s speed by a small amount.

The idea is that if we ever find an asteroid in our path, a future DART-like spaceship can hit it and change its speed enough that, over time, it will miss Earth.

Interestingly, a new paper he just published points out that the impact could have an unforeseen outcome earlier, which would cause the moon to start falling as it orbits the parent asteroid. To be clear, we are in no danger, if that happens, but may complicate a future ESA mission that plans to land a pair of small probes on the moon. It may also have long-term ramifications for the asteroid system.

The asteroid in question is a binary system, a large rock 780 meters wide called Didymos orbited by a smaller moon of 160 meters called Dimorphos*. Together they move along an elliptical path that takes them from 150 million to about 340 million kilometers from the Sun. This orbit can take them less than 6 million kilometers from Earth, so they are classified into Potentially dangerous asteroids, some more than 140 meters wide that reach 7.5 million km from Earth.

That closing of a date does not happen often (i.e. we are safe from this couple for the foreseeable future), but in October 2022 they will pass less than 11 million km from us, which is relatively close. . Not coincidentally, this is the date chosen for the DART mission to impact Dimorphos; in this way, Earth telescopes have as clear a view as possible (we think DART will also have a smaller probe that will be deployed before impact to see the whole event and send data to Earth, making this mission all about duos).

Dimorphos orbits Didymos every 11.9 hours. The impact, which should be equivalent to the explosion of about 3 tons of TNT, is expected to change the orbital speed of the moon by only about half a millimeter per second, enough to shorten the orbital period by a few minutes. DART will use an onboard camera to navigate autonomously, aiming at the center of the moon. This had never been done before, but it would be crucial to any possible future mission to hit an impact asteroid; the farther we get from the Earth, the longer it has to get out of the way, and that means it is possible to send it from the Earth due to the delay in the speed of light.

This kind of idea has been around for a long time (called a “kinetic impactor,” I mentioned it in a TED talk I gave a few years ago) and was even implemented on the Deep Impact mission that crashed into a small comet in 2005. But DART will test a variety of new technologies that should make this mission more reliable.

The new research, however, analyzes what happens not with the orbit of Dimorphos but with the moon itself. The scientists used both mathematical analysis and computer simulations to see what would happen to the moon’s behavior after the impact. What they found is that in many circumstances, the moon can begin to fall chaotically. The orbit will only change a little, but the moon to himself it could begin to change its orientation as it orbits. If you’ve ever seen a toy slow down, the axis of rotation first begins to make a circle, and then just before you stop the axes all over the place. This is as predicted here, although for the moon it will not be such a frantic event.

It will probably start slowly, with the moon tilting a bit, but this will grow over time. Because the moon is not a perfect sphere (really nothing is), it will be unbalanced due to impact. Not only will it tip over, but it will start to fall in a way that is hard to predict.

It’s like the tennis racket theorem: you can spin a tennis racket along its long axis or in a flat turn, but turn it from end to end and it will collapse, making a medium turn. This can also be done with a book or any object that has three different axes of symmetry.

The moon still orbits Didymos well and the combined orbit of the two around the Sun will remain essentially unchanged. But the fall can have some interesting effects.

For one, the European Space Agency is doing a follow-up mission called Hera to the asteroid. Launched in 2024 and arriving in 2026, it will orbit the pair for some time to examine the moon’s orbit very carefully and see how much the impact changed. It will also have two small probes that will examine the moon closely and try to land on it. If Diorphos falls, which complicates things, it makes it harder to know exactly what the best approach is to minimize landing speed and possibly change where the probes land.

In the long run, it could affect the moon’s orbit. Didymos has a weak gravity, but exerts a tidal force on Dimorphos that should tend to align it so that the long axis of the moon points right at Didymos. This may change after impact. If so, the tides will exert a pair on the moon, trying to align it again. There is a complicated interaction between the rotation of an object and its orbit due to the tides (for example, the tides of the Earth cause our own Moon to recede about 4 cm per year), so that as the tides of Didymos act on Dimorphos, the moon could recede or approach its father, depending on the exact conditions of the fall. Although the change will be small, it can be measurable over time (e.g., many years).

Again, this should have no effect on the orbits of the two around the Sun, so this does not put us in danger of impact. But it shows that there can be unintended consequences of the impact.

And that is the main point of this mission. Sure, it’s testing technology to make sure we can do it if the time comes for an asteroid to hit us in the crosshairs, but it’s also good to see what happens when we test it. What if the moon is a pile of rubble (which it probably is)? What if DART plays out of center, or slower or faster than expected, oo or.

If we already knew everything that would happen, we wouldn’t have to experiment like that. It’s better to check everything with a relatively harmless asteroid than to do it when the planet is in line.

*Didymos means “twin” in Greek and Dimorphos means “to have two forms”, which means that the orbit will change after the impact

He proposes the shield of Whipple a Jonathan O’Callaghan, aka @astro_jonny on Twitter, who wrote about it in Technology Review.