However, less than a week later, her parents, her three daughters and an aunt became infected with the Delta variant. She and her husband were not spared. Soon, they also felt bad. Almost everyone had mild symptoms, 2 to 4 days, except father and children.

“My father suffers from chronic leukemia; he had pneumonia, became dehydrated and was hospitalized. If he had not been shot, he would have died,” he said, referring to the Covid-19 vaccine.

Their children, however, were too young to be vaccinated and were severely infected. “My daughters had high fever, cough, vomiting and headaches. I wish they had been vaccinated; I was constantly afraid of them,” she said.

“It is known that in countries where the majority of the adult population has been vaccinated, coronavirus is beginning to target those who remain more vulnerable and children become more infected, as is the case in the United States,” says Dr. Lorena. Tapia, pediatrician and infectologist at the University of Chile and member of the vaccine advisory committee of the Ministry of Science.

“We need to keep moving forward with vaccination among the youngest.”

An early strategy

Different elements explain the success of the vaccination of Chile. Authorities began planning a response to the pandemic very soon. In May 2020, two months after the country reported its first Covid cases, the Ministry of Science began negotiating contracts with different laboratories (Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Sinovac (which is Coronavac) and CanSino) to ensure the purchase of shots for all Chileans.

Simultaneously, the institution worked to get the local scientific community involved in phase 3 clinical trials, which would give priority to the country in the supply of vaccines. Ultimately, commercial offers closed quickly.

“From the beginning, our campaign was based on the benefits of having a diversified vaccine portfolio,” says Science Minister Andres Couve.

“This allowed us to not depend solely on the availability of a supplier, given the high demand for anti-Covid doses worldwide,” he adds.

This strategy, combined with a historically well-organized vaccination system, the creation of 1,400 new inoculation sites and an easily accessible scheduling system by eligible groups, has made it possible to advance the country’s vaccination process with few interruptions.

It helps Chile to have a small population. And their relatively low debt and long-held responsible fiscal policy also mean enough funds to buy enough vaccines. The country’s political and economic stability has even attracted Chinese investment: Sinovac recently announced that it will open a vaccine factory near Santiago next year.

So far, Chile has received 36 million doses for a population of 19 million, enough to have started distributing booster shots. Each week, a new group of people becomes eligible for reinforcers; this week, the country gives benefits to people 55 and older.

“It’s very easy to get vaccinated in Chile and people have been very responsible. The vaccine movement is marginal,” says Eduardo Undurraga, a former CDC researcher and current professor at the Catholic University of Chile.

Historically, Chileans have relied on vaccination campaigns and vaccination skepticism has not taken deep root in the country. In fact, Chile eradicated smallpox 27 years earlier than the rest of the world and was the third country to control polio. Citizens’ confidence in vaccines has also significantly reduced childhood diseases such as measles, mumps and rubella.

The results, published in early July, were reassuring: the study found that their effectiveness was 66% for the prevention of Covid and about 90% for the prevention of hospitalization, l admission to the ICU and death. However, this investigation was done before the first cases of Chileans infected with the Delta variant were reported in late June.

Be vigilant

Although Covid-19 figures are rising again in Central America and the Caribbean, last week Chile reached the lowest infection rate and the number of active cases since March 2020.

The percentage of nasal and throat tampons with positive results has stabilized at less than 1%, which led the government to gradually loosen the containment restrictions … a bit. For example, a curfew at 10pm that has been set since last year has changed at 12am, enough to allow some Chileans to feel that they are finally getting free again.

Immunologists and epidemiologists, however, insist on the need to stay alert. They are especially concerned about the Delta variant, which has been circulating for a few months.

Since then, widespread vaccination has played a key role in preventing a new outbreak, experts say, but it is not enough.

That is why the government has never completely lifted prevention measures, unlike other countries that eased the rules of social distancing after experiencing a decrease in confirmed cases and saw an increase in infections. The wearing of masks is still met, as is social distancing in public places and schools. Borders do not reopen completely and travelers still face significant restrictions.

These actions have allowed Chileans to keep the Delta strain in line so far. But with Covid-19, uncertainty always prevails.

“We can’t say it’s under control,” says Dr. Alexis Kalergis, director of the Millennium Institute of Immunology and Immunotherapy in Santiago. “The pandemic is not over and, if we are not careful, we can have a new outbreak at any time.”

While cautious in attributing declining infection rates only to the immunization process, Kalergis said further expanding vaccination is the best way to prevent the emergence and spread of new ones. strains.

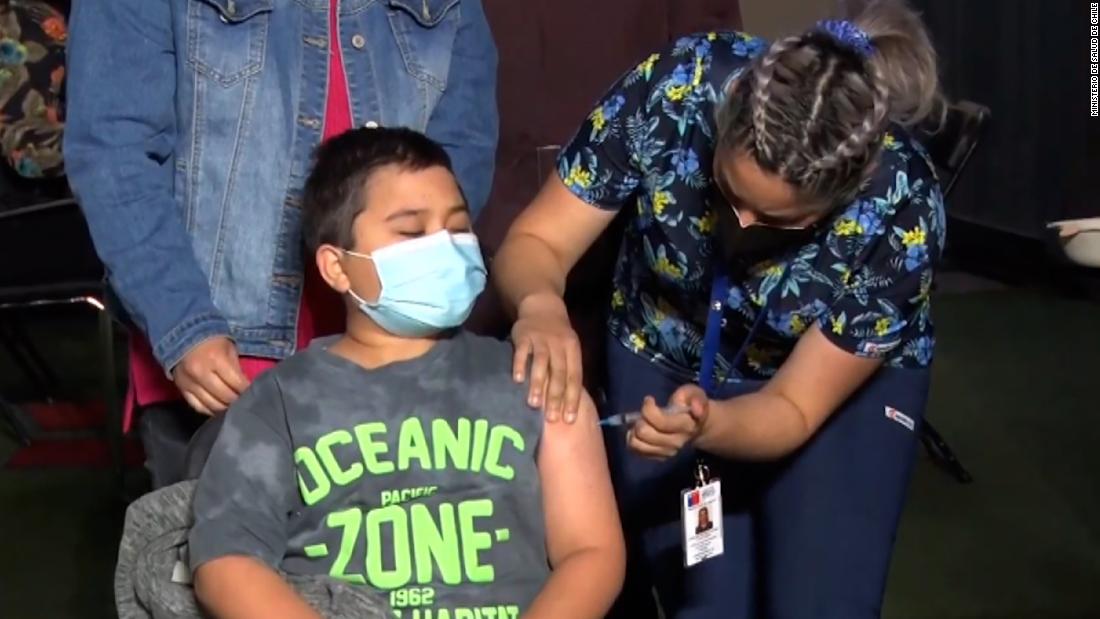

A vaccine for children

Dr. Catterina Ferreccio, an epidemiologist who is part of the Covid-19 advisory committee of the Ministry of Health, explains the urgency: at this stage of the pandemic, she says, it is likely that children will become a reservoir of Covid-19, which it is risky. for them and the rest of the community. There could be at some point a new variant that goes beyond their natural defenses.

Dr. Lorena Tapia, the pediatrician, shares this concern. He also points out that in this country 52% of school-age children are overweight or obese, which increases the risk of suffering serious illness and even death from Covid. There are also a significant number of children with respiratory illnesses.

“It may be true that most children will do well if they are infected, but several will not. And today, with the safety data we manage, it’s something we can prevent.”

Last Monday, Ferreccio participated in the meeting of the Covid-19 advisory committee to evaluate the approval of the CoronaVac vaccine for children between 6 and 11 years old. He says the decision was made based on reliable data provided by China, where more than 40 million children in this age group have been inoculated with CoronaVac and Chile’s long experience with this type of vaccine.

“It’s a well-known vaccine platform; we’re not experimenting. It’s very safe and we’ve seen that when kids are protected, we’re all protected against new strains,” he says.

Also, getting children back to school is an important public health measure in itself, she says.

“As a grandmother of five, I have seen how difficult it has been [children] staying at home, and it gets worse in lower-income families, ”says Ferreccio, the epidemiologist.

“We have seen rising rates of domestic violence and it greatly harms children. For many children school is a protection. Vaccinating them will calm the fears of parents, teachers and epidemiologists. We can’t wait any longer.”