Asked by pro-Beijing lawmaker Eunice Yung about whether the long-awaited M + museum risks “inciting hatred” towards China with some of its artwork, Lam told the Hong Kong Legislative Council which recognized the concern that the institution’s exhibits might cross an unspecified red line. ”

He added that his government respects “freedom of artistic and cultural expression,” but said that since the enactment of national security legislation, which criminalizes acts of secession, subversion, terrorism and collusion with foreign forces, ” all of Hong Kong compatriots are obliged to safeguard national security. “

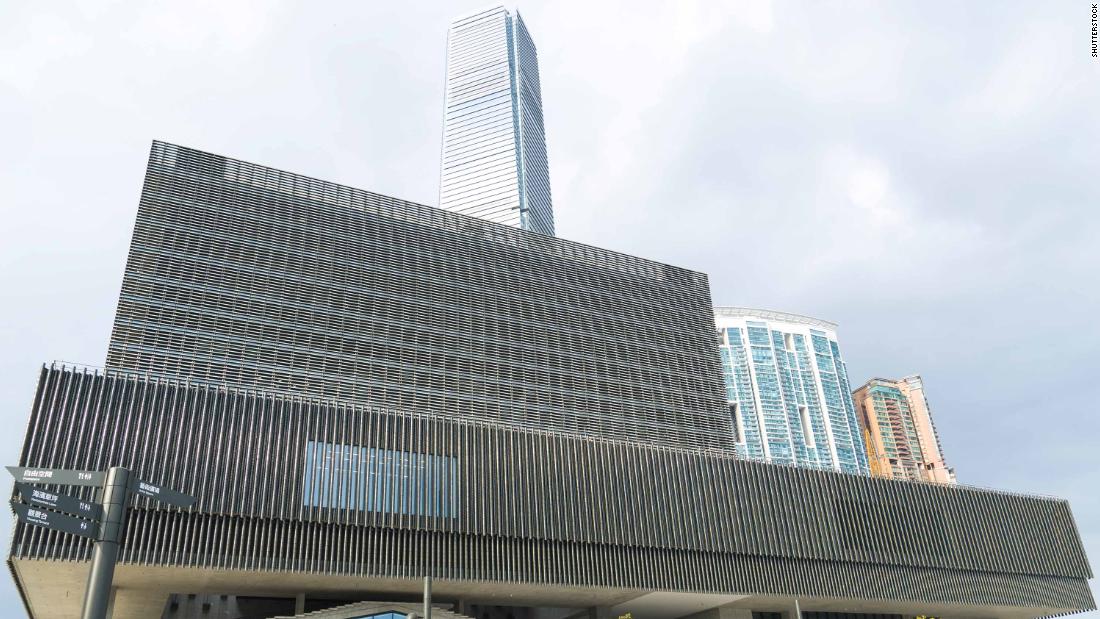

Open to the public at the end of 2021, M + will see 17,000 square meters of exhibition space distributed in 33 galleries. Often presented as Asia’s answer to New York’s Museum of Modern Art or London’s Tate Modern, the ambitious museum is the landmark of the West Kowloon Cultural District, an extensive arts district built on 100 acres of land recovered from the port of Victoria.

But the introduction of the national security law, a response to the pro-democracy protests that shook the city in 2019, has raised concerns about the possibility of censorship (or self-censorship) in the museum.

Process of “cultural politicization”

The museum has not yet revealed which of the works of art in the collection will be shown to the public when it opens later this year. But at a press conference marking the completion of the building last week, director Raffel said there would be “no problem” in showing Ai’s work or the pieces alluding to the massacre of Tiananmen Square.

In a statement issued Thursday to CNN, the publicly funded museum deepened its position by saying it would “comply with Hong Kong laws,” while “maintaining the highest level of professional integrity.”

“The development of the collection and exhibition (of the museum) is based on research and academic rigor,” the statement said. “Like any museum, M + ‘s role is to ensure that our collections and exhibitions are presented in a relevant and appropriate way to stimulate discussion, research, learning, knowledge and pleasure.”

So far, Hong Kong’s national security law has been used primarily against opposition activists and pro-democracy figures, such as media mogul Jimmy Lai. But it has also coincided with the virtual disappearance of the art of protest, as well as the growing use of carefully drafted disclaimers of responsibility by cultural sites trying to distance themselves from possible faults.

For artist Kacey Wong, once fixed regularly in Hong Kong’s pro-democracy protests, the ambiguous wording of the legislation leaves her open to abuse by the authorities.

“The so-called‘ red line ’(by Carrie Lam) is so flexible that it is open for the government or its agents to use to prosecute anyone they don’t like,” Wong said in a telephone interview.

“Hong Kong is experiencing this process of cultural politicization right now,” he added. “It’s like what Ai Weiwei (he said) said, ‘everything is art, everything is politics.'”

According to Wong, these latest controversies collectively point to broader pressure on artistic expression.

“All of these events are united,” he said, adding, “So it’s not just about the collection (roughly) of Uli Sigg, it’s almost a purge within government systems of arts and culture “.

Main image caption: M + museum in Hong Kong