Scientists have generated early-stage human embryo models that could help shed light on the “black box” of the early stages of human development and improve research into pregnancy loss and birth defects.

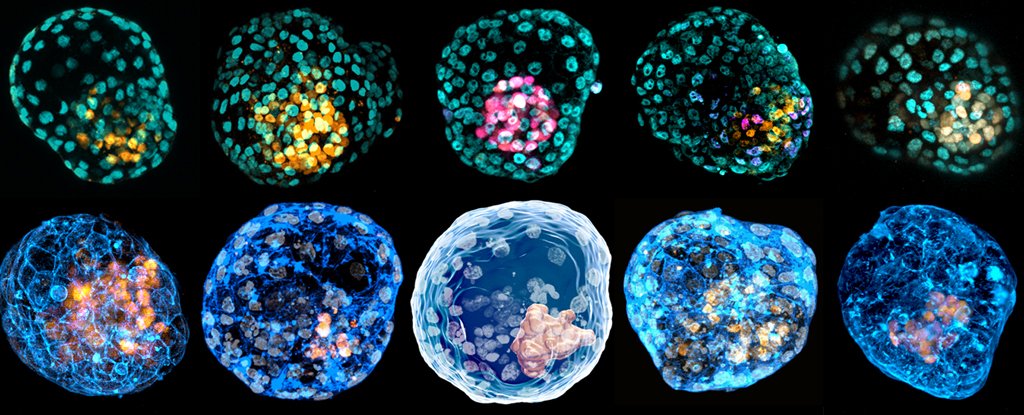

Two separate teams found different ways to produce versions of a blastocyst (the developmental stage about five days after a sperm fertilized an egg), potentially opening the door to a huge expansion of research.

Scientists make it clear that the models differ from human blastocysts and are not able to develop into embryos. But their work comes as new ethical guidelines are being drafted on this research and could spark a new debate.

The teams, whose research was published Wednesday in the journal Nature, believe that so-called “blastoid” models will help investigate everything from miscarriages to the effects of toxins and drugs on early-stage embryos.

“We’re very excited,” said Jun Wu of the University of Texas Southwest Medical Center, who led one of the teams.

“Studying human development is really difficult, especially at this stage of development, as it is essentially a black box,” he told a news conference before the research was published.

Currently, research on the early days of embryonic development is based on given blastocysts from IVF treatment.

But supply is limited, subject to restrictions, and only available for certain research facilities.

So being able to generate unlimited models could change the game, said Jose Polo, a professor at Monash University in Australia, who led the second research team.

“We think this large-scale work capacity will revolutionize our understanding of the early stages of human development,” he told reporters.

To date, the generation of blastocyst models has only been performed in animals, and researchers in 2018 have successfully generated them in mice using stem cells.

The two teams approached the development of a human model in slightly different ways.

Wu’s team used two different types of stem cells, some derived from human embryos and others called induced pluripotent cells produced from adult cells.

Instead, the Polo team started with adult skin cells, but both teams ended up having effectively the same result: the cells began to organize into blastoids, with the three key components being they see in a human blastocyst.

“For us, what was completely surprising was that when you put them together, they self-organized, they seem to talk to each other in some way … and they consolidate,” Polo said.

But while the models are similar to human blastocysts in many ways, there are also significant differences.

The blastoids in both teams ended up containing cells of unknown type and lacking elements that come specifically from the interaction between a sperm and an egg.

Blastoids only worked about 20 percent of the time on average, although teams say it still represents a path to a significant supply of research.

Ethical debate

Scientists are very keen to make it clear that models should not be seen as pseudoembryos and are not capable of becoming fetuses.

However, they proceeded with caution and chose to end the investigation with the blastoids four days after culture, equivalent to about 10 days after fertilization in a normal interaction between eggs and sperm.

Research rules on human blastocysts set this deadline at 14 days.

Peter Rugg-Gunn, leader of the Babraham Institute’s life sciences research group in the UK, said the processes represented “an exciting breakthrough”.

But Rugg-Gunn, who was not involved in the research, said work was needed to improve the current comparatively low success rate of generating blastoids.

“To take advantage of the discovery, the process will need to be more controlled and less variable,” he said.

And given the differences between blastoids and human blastocysts, the models offer the ability to help, but not replace, research on donations, said Teresa Rayon of the Francis Crick Institute, a biomedical research center. .

“They can help generate hypotheses that will need to be validated in human embryos,” he said.

The investigation may also provoke ethical debates, said Yi Zheng and Jianping Fu of the University of Michigan’s mechanical engineering department.

Some “might see human blastoid research as a path to human embryo engineering,” they wrote in an article accompanying the studies in Nature.

The research “calls for public conversations about the scientific importance of this research, as well as about the ethical and social issues it raises.”

© France-Presse Agency