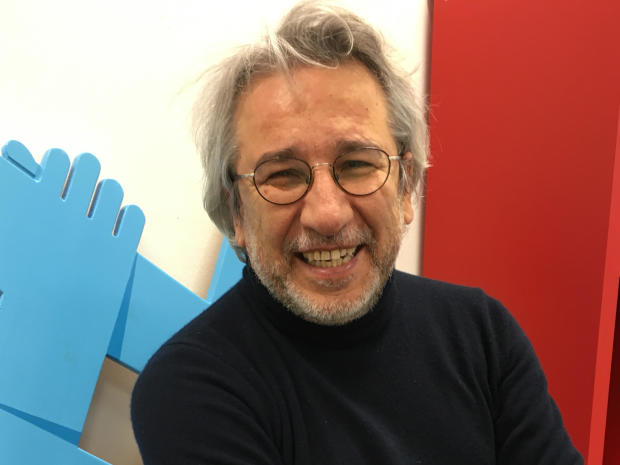

Berlin – Turkish journalist Can Dündar, who lives in exile in Germany, was sentenced on Wednesday to a Turkish court to more than 27 years in prison. The court accused the journalist of obtaining state secrets for espionage purposes. Judge Akın Gürlek also convicted him of supporting terrorism.

The 59-year-old journalist has been living in Germany since the end of the summer of 2016 and there are several ongoing trials against him in Turkey. However, it is unlikely that Germany will extradite the former editor-in-chief of the Turkish newspaper Cumhuriyet.

The most recent verdict was motivated by a report published in Cumhuriyet in 2015, when Dündar was editor-in-chief. In May 2015, the anti-government publication had reported on alleged secret arms deliveries from the Turkish intelligence service to Syrian rebel groups.

According to the Dündar report, the trucks carrying the weapons through Turkey belonged to the Turkish intelligence service MIT. Truck drivers allegedly identified themselves as members of MIT in front of police officers who stopped the vehicles. The trucks had been stopped on two different days in early 2014 in Ceyhan, Adana Province and Hatay. In both cases, the weapons were discovered under a load of medical supplies. The weapons were allegedly grenade launchers complete with projectiles and large quantities of ammunition for machine guns and other weapons.

Dündar allegedly received the information and photos of the smuggled trucks from the hands of Enis Berberoğlu, former chief editor of the big newspaper Hürriyet. Berberoğlu later became a member of parliament for the opposition CHP. He himself was in prison until the summer of 2020.

CBS News

Other Turkish media had also reported on arms smuggling. Aydınlık, a smaller newspaper, had published the report even before Dündar’s Cumhüriyet, but journalists were never convicted of publishing the story.

But Dündar, on the other hand, had been sentenced in 2016 for publishing state secrets.

However, this verdict was later overturned when the Supreme Court had insisted that he should also answer for espionage. After three months in pretrial detention, Dündar was released in early 2016 by order of the Turkish Constitutional Court, shortly after fleeing an assassination attempt during a court trial. Dündar was sentenced to more than five years in prison at the time, but managed to escape to Germany.

Indirectly, the 14th courtroom of the Istanbul jury admitted in its latest verdict that Dündar may have been right in the accusation of illegally supplying weapons to Syrian rebels. Dündar received 18 years and nine months in prison for secret information “for the purpose of espionage.”

However, the charge of illegally publishing state secrets was dropped. The court also sentenced Dündar to eight years and nine months in prison for supporting terrorism. This accusation has been filed against most dissidents in Turkey since the 2016 coup attempt.

CBS News

The Istanbul court based its verdict on a letter that was sent to the UN Security Council in 2015 by Bashir Jaafari, the former permanent representative of the Syrian Arab Republic to the United Nations.

CBS News obtained the letter sent by Jaafari in which he complains to the UN that the Turkish government was trafficking weapons in Syria. As proof of this, Jaafari cites, among others, the article by Can Dündar.

“Now the Turkish government is using this letter as proof that I have spied on the Syrian government,” Dündar told CBS News.

Dündar’s lawyers boycotted the sentence. They accused the court of acting in accordance with the government’s political instructions and violating the rights of the accused. For example, they said, the court had deliberated on the case several times without defense.

Since Dündar fled to Germany, all his property in Turkey had been confiscated a few months ago.

“We waited for that result for five years,” Dündar told CBS News. “They were trying to find the right judge to make this silly verdict because it’s not easy to charge someone with espionage without any evidence.”

“Now they have a letter from a Syrian official who simply cites various reports on the delivery of weapons and Turkish judges call this evidence. It’s ridiculous,” he added.

The opposition calls Judge Akın Gürlek a “Erdoğan trigger”.

Dündar’s wife, Dilek, who joined her husband in exile in the summer of 2019, called the sentence a joke: “Can became Bond 008 overnight, that’s ridiculous.”

Dündar will now go to the European Court of Human Rights. “My lawyers will appeal to the High Court, but I don’t expect anything, because it’s under Erdoğan’s control,” Dündar told CBS News.

“Everyone knows that these decisions and rulings are political and not judicial,” he noted.

President Recep Tayyip Erdogan had repeatedly called Dündar an “agent.” He also rejected on Wednesday a ruling by the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg, which had demanded in the highest instance the release of Kurdish politician Selahattin Demirtaş. As a result, the exclusion of Turkey from the Council of Europe is now likely to be on the agenda.

Critics of Erdoğan’s government see the decision in the Dündar case as further evidence that Turkey is increasingly moving away from European legal norms. The Strasbourg Court of Human Rights on Tuesday demanded the release of Kurdish politician Demirtaş, who has been in pre-trial detention for more than four years. Demirtaş is being held for political reasons, according to European judges.

The Strasbourg court also demanded the release of democratic activist Osman Kavala, who has been in prison for more than three years. Like Dündar, Demirtaş and Kavala had been publicly denounced by Erdoğan as enemies of the state.

As a member of the Council of Europe, Turkey is obliged to apply the Strasbourg verdicts. However, in the case of Demirtaş and Kavala, Ankara refuses to do so.

Turkey is regularly criticized internationally for its systematic restriction of press freedom. The country currently ranks 15th in the international press freedom ranking of Reporters Without Borders.

This verdict is a deterrent to other journalists, Dündar said. “Who would publish this story now knowing they could face decades in prison?”

But he remains optimistic: “Once the political climate changes, all these court rulings will be invalid.”