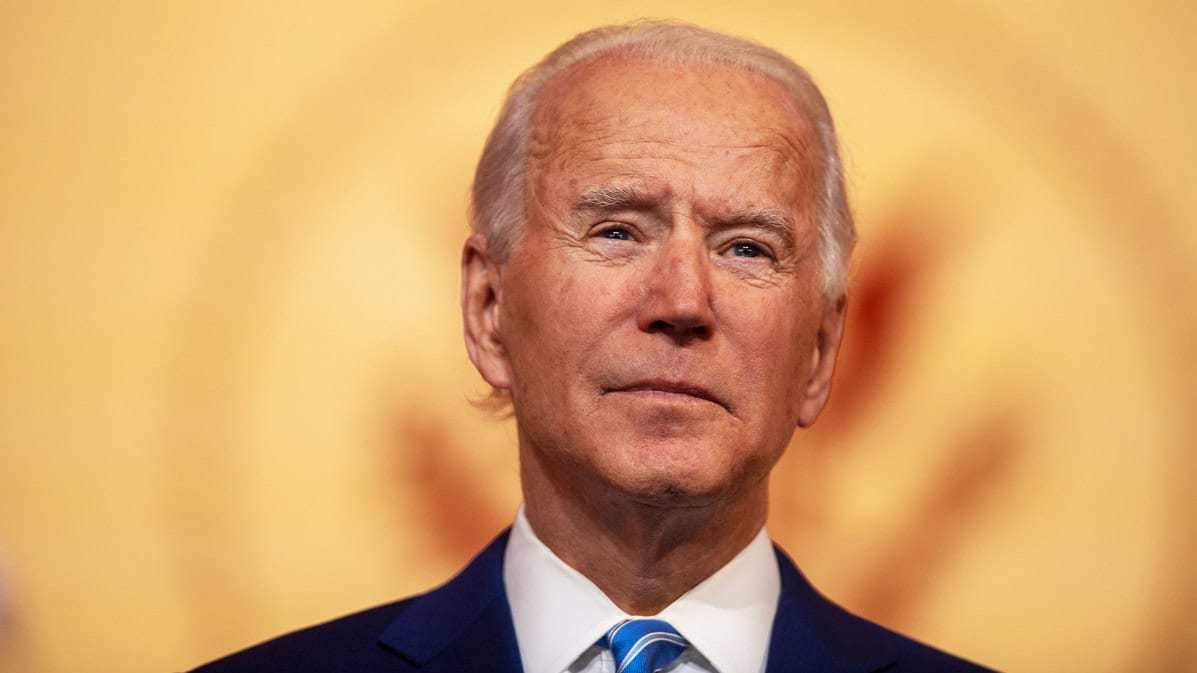

Joe Biden is in a role. His approval rating is higher than his predecessor ever had. Nearly three-quarters of Americans think they are doing a good job managing the COVID pandemic. Sixty percent approve of its handling of the economy.

So now is the time to start looking at what could go wrong and directing your attention beyond our borders. It is no coincidence that the only area where the Biden classification is on our southern border, where its efforts to solve the problems exacerbated by its predecessor have hit problem after problem, all magnified by the knowledge of desperate immigrants that Donald Trump is gone.

But this is not the only place the world will play, and as Biden’s predecessors know, the results are often problematic. Barack Obama was elected to get us out of the George W. Bush wars and his first year he discovered how difficult it would be and ended up raising our troop levels in Afghanistan (due to his vice president’s objections). George Bush was fine until September 11, 2001. Bill Clinton’s first foreign crisis also took place in his first year in office with the Battle of Mogadishu and the notorious Black Hawk Down incident. The first year of George HW Bush’s rule saw both the Tiananmen Square revolt and massacre and a wave of revolutions in the sunken satellite states of the sunken Soviet Union that transformed the geopolitical landscape.

Today is a very different world, but two developing situations involving Russia and China, which are still America’s most important international rivals, point to Biden’s challenges. Russia has increased in recent weeks the deployment of troops and military resources on the Crimean peninsula and along the Russian-Ukrainian border. And China has increased its aggressive stance toward Taiwan and into the South and East China Seas, which is of deep concern to Asian and American military leaders.

While neither the Russian invasion of Ukraine nor the Chinese attack on Taiwan are considered the most likely short-term consequence of its noise, it does not make these situations less risky. In both cases, this is because the stakes in the US, our interests and allies are very high and our effective options are limited. It should also be noted that, in both cases, the possibility of military action by our opponents is not nil.

In Ukraine, several recent diplomatic talks involving, in different combinations, Russians, Ukrainians, Germans, French and the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe have been unproductive. Not surprisingly, the Russians have said that their actions “should not worry anyone at all. Russia is not a threat to any country in the world. “It is not surprising, given its history, that its words were received in disbelief. The Ukrainian army is on alert. Nerves are worn out.

As for Taiwan and the disputed territory in the South and East China Seas, fears are based on years of gradual acceleration of Chinese capabilities. China’s navy has expanded. Deployments and excessive flights to and around disputed areas have grown. Chinese rhetoric has ranged from apology to direct confrontation. Last month, the region’s top U.S. commander told a Senate hearing he hoped the threat against Taiwan would reach the next six years. But the serious problems seem true long before. A few days ago, China announced that the exercises of its carrier group near Taiwan will become regular events and the US responded with a visit by Theodore Roosevelt Carrier Strike Group to the area for the second time this year.

If Russia tried to expand its control over Ukraine or China to intentionally or otherwise provoke a conflict around Taiwan or disputed islands in waters it claims, the consequences would be a major crisis.

The Biden administration has been actively involved on both fronts. The President spoke with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky a few days ago. Days earlier, Secretary of State Antony Blinken spoke with his Ukrainian counterpart and said the US supported Ukraine “in the face of Russian aggression.” During a recent trip to Asia, the secretary of state made it clear that the United States would not advocate Chinese “coercion and aggression” and raised Chinese concerns when he referred to Taiwan as a country. In bilateral meetings, the US stressed these points. This week, the United States expressed its solidarity with the Philippines in opposition to the provocative invasion of Chinese ships in Philippine waters.

Russia’s Vladimir Putin and China’s Xi Jinping are testing, at least to some extent, the Biden administration to see how they will respond to these threats. So far, they have seen clarity and determined toughness. But the reality is that whatever our statements and stated policies, it is unlikely that the U.S. will go directly into military action to defend Ukraine or Taiwan. The potential risk of rapid escalation, major losses and global conflicts is too high.

This means that the Biden team must face these crises before reaching this point. They must forge a united front with allies to show that the negative repercussions of the aggression would be great and that the US will not be isolated. They need to make it clear that there are short red lines of real aggression that will lead to heavy sanctions. They must emphasize that they will provide active support to strengthen the defense of all our allies in the region. They must increase military readiness in a way that sends a clear message. And, above all, they must find diplomatic means to deactivate these tensions.

If they fell short on any of these fronts, even without war, these conflicts could escalate into major distractions, create tension with the Allies, and / or produce an appearance of weakness or inefficiency at home. So far, Biden and his team have made the right moves. They have especially distinguished themselves from Trump with the embrace of both multilateralism and diplomacy, and at the same time have surprised some with the clarity and strength of their responses to the Chinese and Russians.

But the foreign policy issue is that the United States does not have all the cards. An overly far-reaching Putin who seeks to rely on himself at home may resort to his family plot to seek victory near Russia abroad. Naval and air encounters in the Chinatown can easily result in accidental confrontations and consequent escalation. China has also been more brutal recently in Hong Kong and its northwest, suggesting that world public opinion does not let it influence much.

These are not the only potential international risks that could complicate President Biden’s life. North Korea remains a risk. Tensions in the Persian Gulf remain high. The likelihood of setbacks in Afghanistan when we back our presence is also high. In addition, the COVID pandemic is sweeping the world, which could lead to recession, vaccine strains, humanitarian crises and more.

History and current reality work together to provide a compelling reminder, therefore, that if Joe Biden wants to build on his successes to date or keep his momentum on his national agenda, he will need to be mindful of the type of dangers that are achieved around the world. even the most capable of his predecessors.