Economics used to offer many metrics that were intended to show when growing economies were approaching some kind of speed limit. But increasingly, inflation is the only thing that is taken seriously.

A lasting rise in prices would likely convince policymakers that it is time to curb the expansionary measures taken in the pandemic, such as high public spending or low borrowing costs. That’s why Tuesday’s consumer price data in the U.S. will look so close, even though it will take more than a month to change your mind.

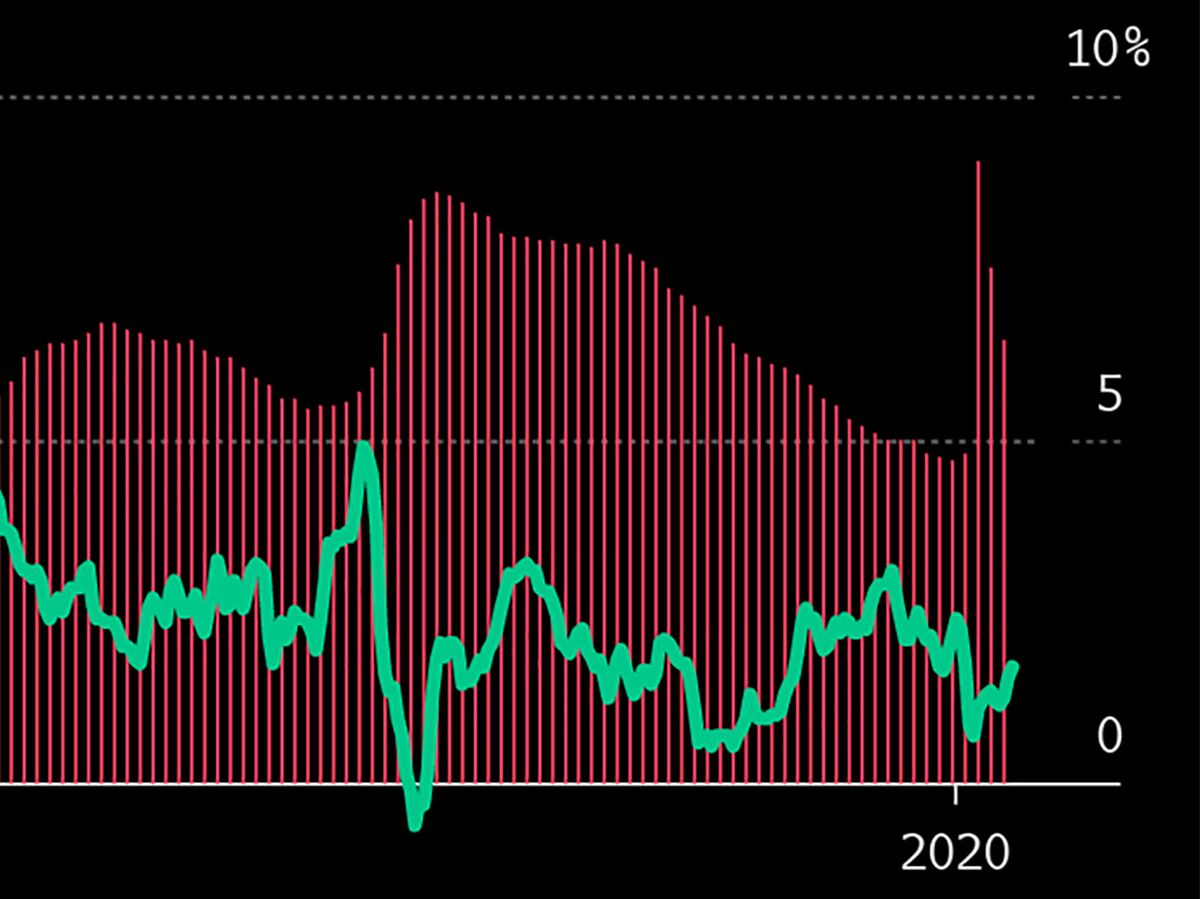

Yesterday’s problem, or tomorrow’s?

Decades have passed since inflation was an urgent issue in the rich world

Source: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development

Meanwhile, as part of a profound shift in economic thinking that has picked up the pace of the past year, a number of other indicators that were once relied upon to tackle the problems of the future are falling out of favor.

It was believed that budget deficits and public debt showed a warning sign at certain levels, until many countries exceeded these limits, especially over the last year, without crashing. Estimates for full employment, or the largest number of jobs an economy could create without overheating, turned out to be erroneous.

The so-called “production gap” measures are supposed to capture the extent to which an economy has reached its maximum capacity, but many analysts have concluded that they rely too much on the recent past to be a useful guide.

Pivot of humility

Abandoning or minimizing all of these criteria means that officials are less likely to take the kind of preventive action that stifled past expansions.

Change is also a pivot to humility, in a profession that is not famous for it. Economists used to be comfortable offering their predictions as the basis of politics. They have to acknowledge that the future is full of things they just don’t know.

“The influence of long-term projections has evaporated, and that’s very good,” says James Galbraith, a professor of economics at the University of Texas. “Design policies to deal with the problems you have. If they have consequences later, you will go later ”.

This philosophy underpins the Federal Reserve’s new interest rate framework. Over the past decade, the central bank began to raise borrowing costs even as inflation fell and unemployment remained at around 5% after the financial crisis.

Now, Fed officials effectively concede that it was a mistake, because the low unemployment did not cause a rise in prices. And now they say they will base politics on what has really happened in the economy, rather than what is expected to happen next.

Room to run

The decade before Covid-19 showed that the US economy could continue to create jobs without causing inflation

Source: Office of Labor Statistics

Three times a during last month’s speech, Federal Reserve Governor Lael Brainard contrasted the “results” with the “prospects” – and said Fed policy will be based on the former, not the latter.

Also in fiscal policy, speed limits have been reconsidered.

Budget deficits and national debt as part of the economy used to be the basic metrics. The European Union imposed 3% deficit limits. Economists Carmen Reinhart and Ken Rogoff, in an influential A study a decade ago argued that debt at 90% of GDP was a dangerous turning point.

This kind of thinking led to austerity policies after the initial shock of the 2008 financial crisis, and the result was a weak recovery. But budget forecasts tend to be too pessimistic because they did not anticipate that interest rates would remain low.

Wrong track

The OBC has consistently overestimated the costs of public debt

Source: Congressional Budget Office

In the pandemic, governments have been more willing to invest, especially in the United States. President Joe Biden is pushing measures worth more than $ 5 trillion during his first year – fuel for what already looks like it will be a faster rebound in the economy.

What heat?

In a way, the new approach aligns with the school of thought called modern monetary theory. MMT says governments have room to boost their economies with fiscal spending and argues that inflation, rather than deficit or debt levels, is the metric that budget authorities should monitor.

“One thing that has caught the mainstream is allowing the economy to run a little warmer,” says Scott Fullwiler, an MMT economist and associate professor at the University of Missouri-Kansas City. “That’s what we’ve been hitting for decades.”

Unfortunately, Fullwiler says, economists have not paid enough attention to the question of what a safe maximum rate would be – and have focused too much on central banks, even though fiscal policy is now pushing for recoveries.

“The economics profession in general has a far enough capacity to figure out how well the economy can function,” he says. It would now have better answers “if economists had been working on fiscal policy frameworks to stabilize the economy and keep inflation low, rather than an optimal monetary policy, which is basically irrelevant.”

“Senseless exit gaps”

In the United States, opponents of Biden spending have invoked the “production gap”: the difference between the goods and services an economy is producing and the maximum it could manage sustainably.

Mind the Gap

The U.S. economy has grown mostly below its potential since the 1980s

Source: CBO Economic Outlook, February 2021

Former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers and the Committee on a Responsible Federal Budget, for example, argued that last month’s stimulus bill was much larger than was needed to close that deficit and, as a result, , risked causing inflation.

But many analysts are skeptical about the measure. Robin Brooks, chief economist at the Institute of International Finance, has been leading a campaign against “meaningless production gaps” for years.

According to him, the production gap is “a very important concept” that underlies all major policy calls. “No one has any idea how it’s measured.”

Production gaps are based on estimates of the potential of an economy. A small deficit means that production is estimated to be approaching its speed limits and that trying to move it forward more quickly could lead to inflation.

But Brooks says the potential is often calculated simply by looking at what happened in the recent past. He argues that when a country has been underperforming for an extended period, such as Italy in recent decades, the result is that its potential is also reduced, which puts an effective limit on how good things should be allowed.

Looser?

Production gap in the fourth quarter of 2020 as a share of potential GDP

Source: Goldman Sachs Economics Research

In a February report, Goldman Sachs economists tested an alternative way to measure and concluded that output gaps in Italy’s major economies in the United States were likely larger at the end of last year than they did. suggest official estimates, meaning there was “more decline.” “, Less risk of inflation and a stronger case for expansionary policy.

Since then, the U.S. recovery has picked up pace, surprising many analysts.

Read more: U.S. jobs are back, amazing entrepreneurs and economists

Galbraith, who was director of Congress ’Joint Economic Committee during the recession of the early 1980s, says emergencies are not the right time for policymakers to try any kind of precision forecasting.

“Don’t try to figure these things out,” he says. “You throw everything you need and much more. And then, if it turns out you’re doing too much (which is unlikely), you reduce the size. “