Several of these buses passed in front of Romana Siddiqui’s house when she took the children out the school door and handed out food and snacks for the day.

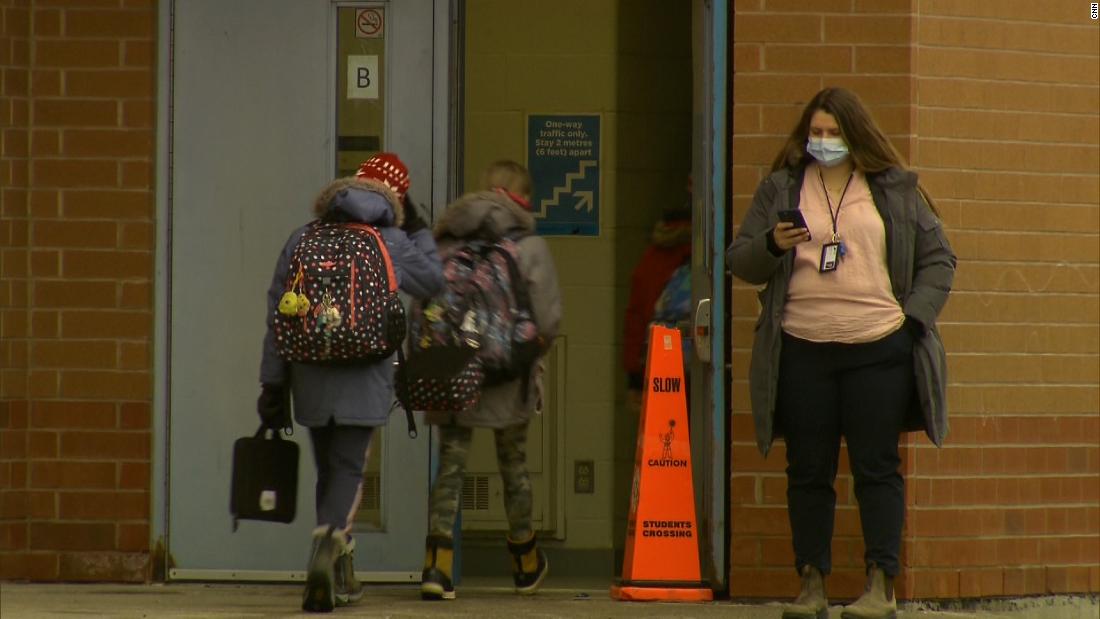

As stressful as the morning rush can be, many Canadian parents are grateful. Through a dangerous second wave of pandemic, Canada has managed to keep most schools open, most of the time, even at the most affected points of Covid-19.

“I’ll be honest, sometimes I’m nervous,” Siddiqui says in an interview on CNN outside of her children’s school, “But the quality of their learning is much better in class, you can’t compare the virtual with the in class. So learning didn’t really happen at home. “

Already last spring, and reinforced by medical experts, the Canadian provinces and territories responsible for education tried to keep the axiom too often ignored; schools should be the last to close and the first to reopen.

The result has been an uneven mosaic with some jurisdictions offering virtual and face-to-face options, others imposing a hybrid model for older students.

Adam, Siddiqui’s 16-year-old son, Adam, the eldest of his three children, has had face-to-face learning this school year, but it is now virtual.

“For next year, I just hope we get back in person,” Adam says, describing a school experience that has been far from normal, either in person or online.

Less than an hour’s drive from Mississauga, Mark Witter makes his rounds during recess reminding children to “stay in their areas”.

But except for the masks, even outside, the views and sounds are extraordinarily comforting, the children enjoy the winter sun and are clearly happy to be with friends at school.

“I was very excited to get them back. It was different. But we worked to understand a lot with students and families and explain what our new routines were, but also try to make sure things were so typical. as they might be, ”said Witter, principal of St. Francis of Assisi Catholic Elementary School in the Halton region of Ontario.

The protocols adhere to guidelines set by provinces, school boards and local public health officials. Students at this school in Georgetown, Ontario, are in cohorts for classes and recreation, there is a detailed Covid-19 screening procedure for educators, students and visitors, and a universal costume both inside and outside the school. .

When classrooms were set up across the country for mass reopening in September, even Justin Trudeau, the Canadian prime minister, admitted it was a difficult decision for his family.

“We’re seeing what the school plans are. We’re looking at class sizes. We’re seeing how kids feel about wearing masks,” Trudeau said when asked during a press conference last summer adding, “Like so many parents, this is something we are in very active discussions about.”

Trudeau and his wife, Sophie Grégoire Trudeau, finally decided on face-to-face learning from their 3 children attending public schools in the Ottawa area.

But the reality of keeping everyone in school and avoiding the virus turned out to be a challenge in a few weeks after the school reopened in September.

Witter says two classrooms were sent home for two weeks of e-learning and seven positive cases were identified. But the school remained open.

From British Columbia to Ontario and Quebec, Canada’s top provincial doctors have said schools have not been a major source of the virus’s spread and that outbreaks in educational settings reflect the level of transmission to the community at large.

Witter also credits students for helping keep schools open as they learn and adapt to the “science” that is now part of their daily curriculum.

“They keep the masks on, follow their teachers’ instructions, wash their hands. So it’s been really fun to see and just a comforting thing that the students themselves have committed to public health measures as well,” he said. says Witter.

Almost universally, government and education leaders have praised teachers during this pandemic, many of whom have carried much of the burden to ensure students are safe, happy, and continue to learn.

Armed with a face shield and a mask and a seemingly unbreakable spirit, Andrea O’Donnell organizes and cleans her kindergarten class at St. Francis of Assisi. She admits she herself was skeptical that security protocols would work well enough to keep schools open.

“How will I do it? How will I keep these masks on all those little kids ages 4 and 5? How will they be able to distance themselves physically?” She says adding, “And then I thought, you know, we teach these kids, you know, I’m competent, capable. Yes, we can do it. And yes, we did.”

O’Donnell says his classroom, his school and his school board are “a living test” that keeping children’s learning in person can be done and adds that there are good reasons to try.

“Am I worried about getting Covid? Yes,” he says, “I’d rather be in the classroom a lot. You know, I was very happy when they let us back. Just seeing their faces again, it just brings a lot more joy to be with them.” .

Canadian unions representing educators across the country have expressed their vocation on the demand for more PPE, smaller classes, more teachers and better ventilation for schools.

Although the problems have been controversial, the worst cases of dangerous outbreaks of Covid-19 in schools have been largely avoided.

“It’s a mixed bag. I mean, there have certainly been occasional closures and widespread closures. But you know, we absolutely agree with the perspective that schools should be a high priority to keep schools open,” he said. Harvey Bischof, president of the Ontario Secondary School Teachers’ Federation.

This collaborative approach to keeping schools open has been far from perfect, but the commitment has been its hallmark through two deadly waves of the virus and blockages and closures.

“It’s been stressful, it’s been emotional at times. We’ve had to understand that and let go of a lot of expectations,” Siddiqui says.