With browser manufacturers constantly reducing third-party tracking, advertising technology companies are increasingly adopting a DNS technique to circumvent these defenses, posing a threat to web security and privacy.

Called Cloaking CNAME, the practice of blurring the distinction between own and third-party cookies not only causes the filtering of sensitive private information without the knowledge and consent of users, but also “increases [the] a threat to web security, ”a group of researchers Yana Dimova, Gunes Acar, Lukasz Olejnik, Wouter Joosen and Tom Van Goethem said in a new study.

“This tracking scheme takes advantage of a CNAME record in a subdomain so that it is from the same site as the included website,” the researchers told the newspaper. “As such, defenses that block third-party cookies become ineffective.”

The results are expected to be presented in July at the 21st Symposium on Privacy Enhancement Technologies (PETS 2021).

Increased measures against monitoring

Over the past four years, all major browsers, with the notable exception of Google Chrome, have included countermeasures to curb third-party tracking.

Apple set up the ball with a Safari feature called Intelligent Tracking Protection (ITP) in June 2017, setting a new privacy standard on computers and mobiles to reduce cross-site tracking by “further limiting cookies and other website data.” . Two years later, the iPhone maker outlined a separate plan called “Attributing Privacy Preserving Ads” to make online ads private.

Starting in September 2019, Mozilla began blocking third-party cookies in Firefox by default using a feature called Enhanced Tracking Protection (ETP), and in January 2020 Microsoft’s Chromium-based Edge browser followed suit. Subsequently, in late March 2020, Apple updated ITP with the complete blocking of third-party cookies, among other features designed to thwart login fingerprints.

Although Google earlier this year announced plans to phase out cookies and third-party crawlers in Chrome in favor of a new framework called a “privacy sandbox,” it is not expected to be released until 2022. .

Meanwhile, the search giant has been actively working with advertising technology companies on a replacement proposal called “Dovekey” that aims to supplant cross-site tracking functionality using privacy-focused technologies to run personalized ads on the web.

Cloaking CNAME as an anti-tracking evasion scheme

Faced with these barriers that kill cookies to improve privacy, marketers have begun to look for alternative ways to evade the absolutist stance taken by browser manufacturers against cross-site tracking.

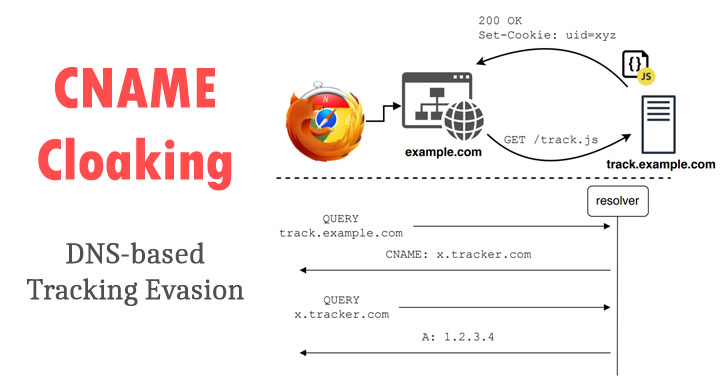

Enter canonical name concealment (CNAME), where websites use top-notch subdomains as aliases for third-party tracking domains using CNAME records in DNS settings to avoid follower blockers.

CNAME records in DNS allow you to assign one domain or subdomain to another (i.e., an alias), making them an ideal means of smuggling tracking code under the guise of your own subdomain.

“This means that a site owner can configure one of their subdomains, such as sub.blog.example, to resolve it to thirdParty.example, before resolving it to an IP address,” explains the engineer. WebKit security, John Wilander. “This happens below the web layer and is called CNAME concealment: the thirdParty.example domain is hidden as sub.blog.example and therefore has the same powers as the real first.”

In other words, CNAME concealment makes the tracking code appear to be first-hand when in fact it is not, and the resource is resolved using a different CNAME than the first-party domain.

Not surprisingly, this monitoring scheme is gaining momentum, growing by 21% in the last 22 months.

Cookies filter sensitive information to crawlers

The researchers, in their study, found that this technique was used in 9.98% of the top 10,000 websites, in addition to discovering 13 providers of these “tracking services” on 10,474 websites.

In addition, the study cites an “Apple Safari web browser-specific treatment,” in which ad technology company Criteo specifically switched to CNAME concealment to prevent browser privacy protections.

Given that Apple has already launched some lifetime-based defenses to disguise CNAME, this finding it is more likely to reflect devices that do not run iOS 14 and macOS Big Sur, which support the feature.

Perhaps most troubling of the revelations is that cookie data leaks were found in 7,377 sites (95%) of the 7,797 sites using CNAME tracking, all of which sent cookies containing private information such as full names, locations, addresses email and even authentication cookies to crawlers from other domains without the explicit statement of the user.

“Is it really ridiculous even, because why would the user consent to a third-party tracker receiving totally unrelated data, including those of a sensitive and private nature?” Olejnik wonders.

With many CNAME crawlers included over HTTP as opposed to HTTPS, researchers also raise the possibility that a request that sends analytics data to the crawler may be intercepted by a malicious adversary in what is a man-made attack. in-the-middle (MitM).

In addition, increasing the attack area that involves including a crawler on the same site could expose a website’s visitor data to session fixation and scripting attacks between sites.

The researchers said they worked with tracking developers to address the issues mentioned.

Mitigating CNAME concealment

While Firefox does not prohibit the appearance of CNAME out of the box, users can download a plugin like uBlock Origin to block these crawlers first hand. By the way, yesterday the company began deploying Firefox 86 with Total Cookie Protection that prevents tracking between sites by “confin”[ing] all cookies on each website in a separate cookie jar. “

On the other hand, Apple’s iOS 14 and macOS Big Sur include additional safeguards that rely on its ITP feature to protect third-party CNAME concealment, though it doesn’t offer a means to unmask the crawler’s domain and block it. from the beginning. .

“ITP now detects third-party CNAME covert requests and limits the expiration of cookies set in the HTTP response to seven days,” Wilander detailed in a letter in November 2020.

So does the Brave browser, which last week had to release emergency fixes for an error that occurred as a result of adding a CNAME-based ad blocking feature and, in the process, went send queries about .onion domains to public Internet DNS resolvers instead of using Tor nodes.

Chrome (and, by extension, other Chromium-based browsers) is the only glaring omission, as it doesn’t block CNAME covertly natively or make it easy for third-party extensions to resolve DNS queries by obtaining CNAME records before send a request unlike Firefox.

“The emerging CNAME tracking technique […] evades anti-monitoring measures, “Olejnik said.” It introduces serious security and privacy issues. User data is filtered, persistently and consistently, without the user’s awareness or consent. This is likely to trigger clauses related to RGPD and e-privacy. “

“In a way, that’s the new minimum,” he added.