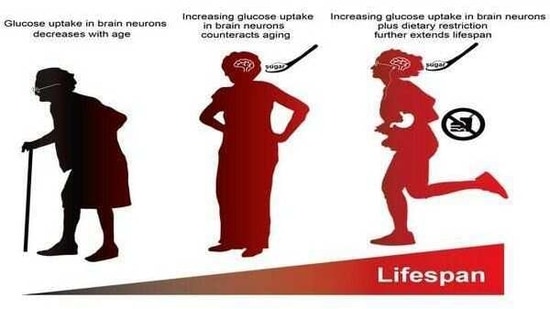

Researchers at Tokyo Metropolitan University have found that fruit flies with genetic modifications to improve glucose uptake have a significantly longer shelf life.

By observing the brain cells of aged flies, they found that better glucose uptake compensates for age-related impairment of motor functions and leads to longer life. The effect was most pronounced when combined with dietary restrictions. This suggests that a healthier diet and better glucose uptake into the brain can lead to improved lifespan.

The brain is a particularly power-hungry part of our body, which consumes 20% of the oxygen we take in and 25% of glucose. That’s why it’s so important that you can stay fed, using glucose to produce adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the body’s “energy message”.

This chemical process, known as glycolysis, occurs both in the intracellular fluid and in a part of the cells known as mitochondria. But as we age, our brain cells are less adept at producing ATP, which correlates with broad strokes with less glucose availability.

This might suggest that more food to get more glucose might be a good thing. On the other hand, it is known that a healthier diet really leads to a longer life. Unraveling the mystery surrounding these two contradictory knowledge could lead to a better understanding of healthier and longer life.

A team led by Associate Professor Kanae Ando studied this problem with Drosophila fruit flies. First, they confirmed that brain cells from older flies tended to have lower ATP levels and lower glucose absorption. They specifically related it to lower amounts of enzymes needed for glycolysis.

To counteract this effect, they genetically modified the flies to produce more than one glucose transporter protein called hGut3. Surprisingly, this increase in glucose uptake was all that was needed to significantly improve the amount of ATP in cells.

More specifically, they found that more hGut3 led to a smaller decrease in enzyme production, counteracting the decrease with age. Although this did not lead to an improvement in age-related damage to mitochondria, they also suffered minor impairment of locomotor functions.

But this is not all. In another twist, the team has subdued dietary restrictions on flies with better glucose uptake to see how the effects interact. Now, flies had an even longer lifespan.

Interestingly, the increase in glucose uptake did not actually improve glucose levels in brain cells. The results point to the importance not only of the amount of glucose there is, but of its efficiency when used once in cells to produce the energy the brain needs.

Although the anti-aging benefits of a restricted diet have been demonstrated in many species, the team was able to combine it with improved glucose uptake to take advantage of both benefits for a even longer shelf life in a model organism. A later study can provide vital clues as to how we can keep the brain healthier for longer.

Follow more stories at Facebook i Twitter

This story has been published from a wireless agency channel without text modifications. Only the headline has been changed.