After nearly six decades as a photographer, Richard Drew has learned a basic rule: “You can get there two hours early, but you can’t get to a late 60s. In other words, if it’s not there, when it happens , no photo can be taken “.

Drew, who has worked for the Associated Press for the past 51 years, was in time to capture Frank Sinatra escorting Jackie Onassis … Muhammad Ali punched … and Ross Perot burst into the 1992 presidential race in a way that captured pepper billionaire, helped AP win the Pulitzer Prize.

But on September 11, 2001, when he took one of the most outrageous images of the day, he was not at the World Trade Center at 8:46 a.m. or 9:03 a.m., when the planes touched down. the towers. She had been assigned to a maternity fashion show in Midtown when her office said, “A plane has hit the World Trade Center very calmly,” she recalled.

He boarded the subway and exited at the southern tip of Manhattan.

Correspondent John Dickerson asked, “When did you start taking pictures?”

“By the time I got off the subway,” Drew replied.

“What goes through your mind when you take them?”

“Everything is thoughtful. You just do it. You just do your job.”

CBS News

“All your senses increase; then, on the other hand, do you basically have to close something in order to be able to do your job?”

“Yes,” Drew said. “You just have to pretend it’s not there. You just have to do what you do.”

Richard Drew has been “doing his thing” since he was 19 when, when he grew up in a Los Angeles suburb called Temple City, he bought a police scanner: “And he listened to the police and then he could, you know, go chasing a car accident or a fire or something. ”

If he wasn’t chasing the latest news, he learned to get close to where the news might get.

On June 5, 1968, he decided to see Presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy speak at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles. “The office didn’t know I was there; I just assigned myself to go to this job,” he said.

Drew went into the kitchen looking for a glass of water. Robert Kennedy was there too. So was an armed man.

As the 42-year-old senator lay on the floor, Drew climbed to a table photographing the chaos. Kennedy’s wife approached Drew and the other photographers.

“I also have a picture of Ethel going that. You know, like, “No, please don’t take pictures of this.” She asked us and the UPI photographer not to photograph her. “

Dickerson asked, “What did you think when Ethel said, ‘Don’t take the picture’?”

“Well, that was his choice, but not mine.”

“What is Yours third? “

“My job is to record the story and I record it every day.”

“What if you stick to that rule?”

“You’re not a journalist,” Drew replied. “Then you’re just a person with a camera.”

Dickerson asked, “What’s the difference between a photograph and just an image?”

“Whether you want to look at it.”

Or, in the case of his most famous photograph, if you want to look the other way.

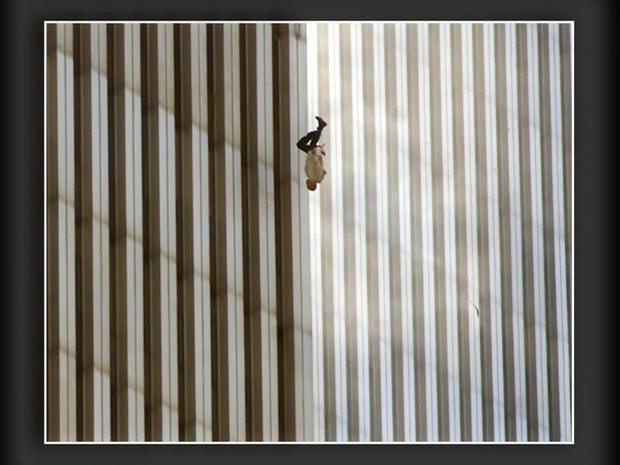

Warning: graphic image:

Richard Drew / AP

Dickerson asked, “When you made the image of ‘Falling Man,’ did you know you had done something extraordinary?”

Drew said, “I didn’t take the picture. The camera took the picture of the man falling. And when these people fell, I would put my finger on the trigger of the camera and hold the camera, and photograph them and follow them. going down, and then the camera would open, close, and take pictures as they went down.I think I have eight or nine frames of this gentleman falling, and the camera just passed by at that point when it was completely upright. see that image really until I went back to the office and started looking at my things on my laptop. I didn’t see them. “

“Were you scared when you took pictures the day you were at the World Trade Center?” Dickerson asked.

“Not really,” he replied. “It’s interesting that this camera is a filter for me. I didn’t know the building, the first building, had collapsed because I was looking at it through a telephoto lens. And I only see a piece of what’s going on.”

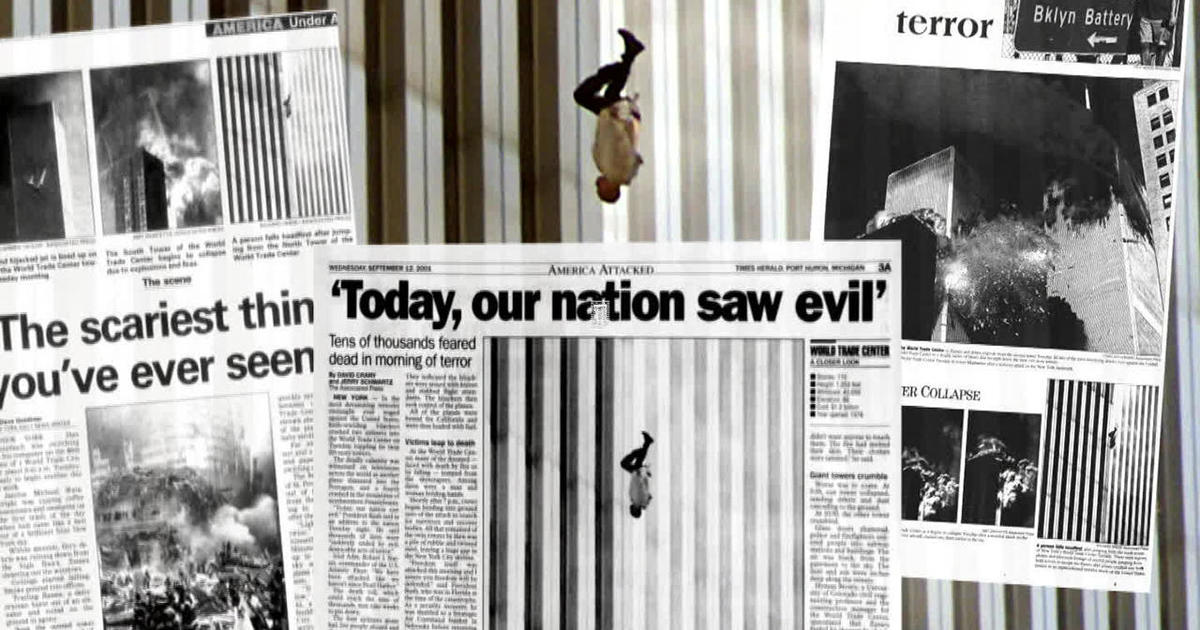

The image of Drew, who became known as “Falling Man,” appeared in several newspapers the next day. Many people found the lonely vision too shocking.

A high-profile spectator was fascinated by his deeply human attraction. Five years ago Sir Elton John told “Sunday Morning” correspondent Anthony Mason that that he it had to buy the photo for your personal collection. “It’s not a shot a lot of people would want to hang on the wall,” John said.

Mason asked, “Why did you want that?”

“Because, again, it’s just the most incredible … it’s the most beautiful image of something so tragic. It’s probably one of the most perfect photographs ever taken.”

Twenty years after the attack, he captures, perhaps more than any other image, the horror of that day.

Drew said, “It’s still kind of that image.” They verbote it.

“Why do you think they have that reaction?”

“Because they can identify with it. I think they can identify that this could be jo. “

“When you look at the pictures you took of that period today, what do you think?”

“I think I would do the same,” he said. “It wouldn’t change anything,” because, as I said before, it’s my job to record the story. “

Dickerson said, “An image stops a moment in time. It captures a moment in time.”

“And hopefully I can stop a reader right now to get their attention. And that’s what it’s really about.”

“And is it about transporting them back to that time?”

“It’s to show them what happened at the time, that they weren’t there to see,” Drew said. “I have this privilege that I can do this.”

“And can the reader come to his own conclusions?”

“They can also come to their own conclusion about ‘Falling Man,’ and that’s what it’s all about.”

The identity of the falling man has never been determined, although journalists have found two possibilities. Their names, Jonathan Eric Briley and Norberto Hernandez, are just a separate name on the parapets of the 9/11 Memorial.

But Drew was able to help identify another victim that day: “I don’t remember how many real people I photographed during it, but it wasn’t just one or two people. A gentleman called the AP and said he knew what the his promise he used that day and they hadn’t recovered his body or anything.And he wondered if I could look at my photographs in the AP. say, “Oh, that’s her.” And that was it. “

For a month after the attack, Drew photographed the aftermath: “And my cell phone rang. And it was my daughter. And she said, ‘Dad, I just want to tell you I love you.’ , he calls me on September 11, no matter where he is to say, “Father, I love you. Because maybe I wouldn’t have survived.”

Twenty years of phone calls that, in an instant, evoke the fiery emotions of that day … just like Richard Drew’s photographs.

For more information:

Story produced by Jay Kernis. Editor: Joseph Frandino.