In 2016, on a sunny winter day, marine biologist Yoshihiro Fujiwara anchored off the coast of central Japan, measuring eels with flirtations, when suddenly a barbarity erupted aboard the ship. The crew of the Shonan Maru had just landed a large, strange-looking fish.

“Wow! We have a coelacanth!” they joked as they carried such a large specimen that it evoked the legendary “living fossil” species found only in Africa and Indonesia.

JAMSTEC

Fujiwara, whose specialty is “whaling” communities – the rich ecosystems that spring around and feed on whale canals – was equally exciting and skeptical.

“It was exciting,” he told CBS News. “But this is a very well-studied bay.”

In fact it is. Since the 19th century, researchers have been building a taxonomy of specimens from Suruga, the deepest bay in Japan.

The area is also one of the most fishing in the world. Surely, Fujiwara thought, someone had seen this colossal creature before.

Surprisingly, no one had any. Fujiwara and his team from the Japan Agency for Earth and Marine Science and Technology (JAMSTEC) checked the reference books and consulted with colleagues around the world before concluding the creature with purple spear shape of the depths, in fact, was a discovery in good faith.

Three more specimens of the monster fish would stick that year, be quickly preserved in formaldehyde, or frozen for later examination in the laboratory.

JAMSTEC

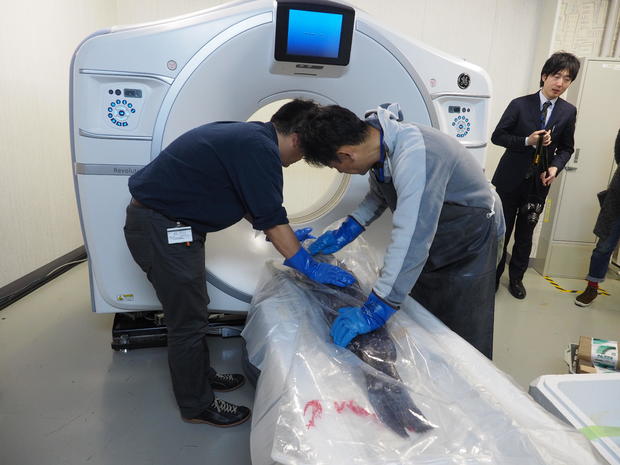

Dissection, computed tomography, and other analyzes placed the specimen within the alepocephaly family, a species of deep water distributed throughout the world and popularly known as “sliding layers”, for their heads and gill covers free of scales. But unlike her much younger relatives, who average only 14 inches in length, this one was a beast: at 55 inches long and 55 pounds, she was the size and weight of a small child.

Fujiwara and his team decided to name the new species “yokozuna slickhead”, according to the highest rank in sumo wrestling.

“I couldn’t believe it,” biologist Jan Yde Poulsen, an associate researcher at the Australian Museum and head of authority, told CBS News from his base in Denmark.

Poulsen, who co-authored an article in January with the JAMSTEC team on the yokozuna header, was also hesitant when he received the first photo from the Fujiwara team.

“It’s a very grainy photo, almost like when you see a photo of the Loch Ness monster,” he said. “Finding a new species that weighs 25 pounds is amazing.”

Despite its hostile habitat of deep, black sea, the spot was not only large, but thick. Although other thick-layered species swallow plankton and weak swimmers such as jellyfish, DNA examination of the giant fish’s stomach contents showed that it hunted other fish, perhaps complementing its sweeping diet.

Unlike other world-famous centaur species, the yokozuna is a vigorous swimmer, possibly capable of covering long distances, as evidenced by a few seconds of rare video captured with a bait camera at a depth of nearly 8,500 feet.

JAMSTEC

Slickhead’s “wide open mouth” mouth houses several rows of teeth, evoking an alien monster. Fujiwara’s team tried to count the densely packed tusks and their strictly unofficial conclusion: “80 to 100” teeth in these jaws.

Physical attributes, in addition to biochemical analysis, identified the yokozuna head as an apex predator, the tall version of a lion or killer whale.

“We have so many dives all over the world,” Fujiwara said. “But it’s weird to see a superior predator.”

The well-equipped marine agency owns a large number of sophisticated submersible vehicles and other deep-sea exploration vehicles, “but they are very noisy and use bright light,” Fujiwara said. “Most major predators are very active, so they can easily escape our submarine.”

His team determined that deploying specially made long lines (long enough to reach the ocean floor, equipped with hundreds of hooks with mackerel baits) would be more effective, though time-consuming. It takes up to four hours to deploy these ultra long lines, which are left in the water overnight.

Although hundreds of new species of fish are identified each year, the deep, hard-to-reach sea still holds many mysteries.

“We have no idea what’s out there,” Fujiwara said.