AAmericans are likely to think of New Year’s Eve and New Year’s Day as a time to celebrate the new beginning that represents a new year, but there is also a troubling side to the history of the holidays. In the years leading up to the Civil War, the first day of the new year was often a heartbreaking one for American slaves.

In the African American community, New Year’s Day used to be widely known as “Day of Recruitment,” or “Love Day,” as described by African American abolitionist journalist William Cooper Nell, because enslaved people passed away. New Year’s Eve waiting, wondering if their landlords would rent them to someone else, thus dividing their families. Slave labor rental was a relatively common practice south of the antelope, and a profitable practice for white slave owners and contractors.

“Recruitment Day was part of the largest economic cycle in which most debts were collected and settled on New Year’s Day,” says Alexis McCrossen, an expert on New Year’s Eve history. Year and New Year and professor of history at Southern Methodist University, who writes about the day of recruitment in his next book Time’s Touchstone: The New Year in American Life.

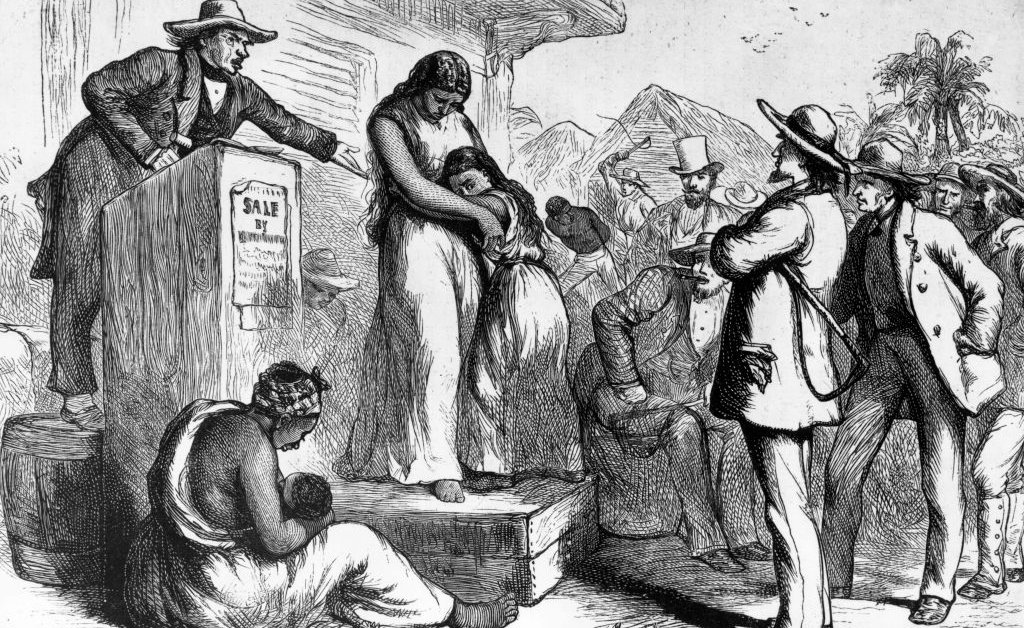

Some enslaved people were put up for auction that day or kept under contracts that began in January. (These transactions also took place throughout the year and the contracts could last different amounts of time.) These deals were carried out privately between family, friends, and business contacts, and slaves were delivered to the squares of the city, on the stairs of the court and sometimes simply on the side of the road, according to Divided Mastery: Hiring slaves in South America by Jonathan D. Martin.

The accounts of the cruelty of the Day of Recruitment come from the records left by those who secured their freedom, who described spending the day before January 1 with the hope and prayer for their contractors to be human. and that their families could stay together.

“Of all the days of the year, slaves fear New Year’s Day the worst of all,” said a slave named Lewis Clarke in an 1842 account.

“On New Year’s Day, we went to the auctioneer’s block, to be hired by the highest bidder for a year,” Israel Campbell wrote in a memoir published in 1861 in Philadelphia, in which he describes being hired three times.

“There’s what he does that says what he does on New Year’s Day that you’ll do all the rest of the year,” a former slave known as Sister Harrison said in a 1937 interview.

Get history correction in one place – sign up for the weekly TIME history newsletter

Harriet Jacobs wrote a particularly detailed account in the chapter “Slave New Year’s Day” in her 1861 autobiography. Joincidents in the life of a slave girl. “The day of hiring in the south takes place on January 1. Al 2[n]d, slaves are expected to go to their new masters, “he wrote. He noted that slave owners and farmers rented their human home for additional income during the period between cotton and wheat harvests. Moorish and the next planting season.From Christmas to New Year’s Eve, many families “waited anxiously” to see if they would be rented and to whom. the grounds are full of men, women and children, waiting, like criminals, to hear the sentence, ”Jacobs wrote.

On one of those fateful days, Jacobs saw “a mother driving seven children to the auction. I knew some would be taken; but they took everything away ”. The slave trader who carried the children would not tell him where he was taking them because it depended on where he could get the “highest price.” Jacobs said he would never forget his mother shouting, “She’s gone! All gone! Because no Does God kill me? ”

The enslaved people who were trying to resist going to their new masters were whipped and thrown in jail until they gave in and promised not to flee during the new agreement. Older slaves were also particularly vulnerable, as Jacobs describes an owner who tried to hire a fragile woman in her 70s because she was moving away.

But the story of New Year’s Day and American slavery is not all horror. Holidays were also associated with freedom.

The federal ban on the transatlantic slave trade came into force on New Year’s Day 1808, and African American communities did celebrate, but the festivities were short-lived.

“Different commemorations of the abolition of the slave trade took place between 1808 and 1831, but they were extinguished because the internal slave trade was so vigorous,” says McCrossen. The risk of violence was also too great. For example, on New Year’s Eve 1827 in New York City, a white mob attacked African-American congregants and vandalized their church.

Holidays were associated more with freedom than slavery when Abraham Lincoln signed the Proclamation of Emancipation, freeing slaves in the Confederate states on New Year’s Day 1863. Slaves went to church to pray and they sang on December 31, 1862 and so there are still New Year’s Prayer Services in African American churches across the country. In these “Watch the Night” services, congregants continue to pray for more widespread racial equality 157 years later.

Correction, December 27th

The original version of this story misrepresented the year of an attack on an African American church on New Year’s Eve in New York City. It was 1827 and not 1927.