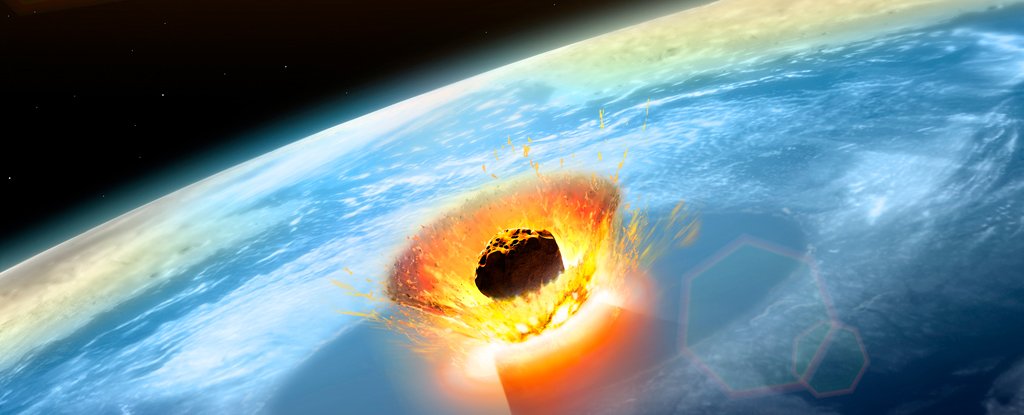

After dominating the planet’s surface for hundreds of millions of years, the diversity of dinosaurs came to a dramatic conclusion about 66 million years ago at the end of the impact of an asteroid with what is now the Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico.

It is such an inflated theory of data that it is hard to imagine that there is any doubt that this is what happened. If it was a cold case, it would now be rubber stamped and filed in the “Resolved” section.

But scientists are a baffling group and a small gap in the chain of evidence linking the signs of a global apocalypse to the crime scene has been calling for it to close.

An international team of researchers collaborating in a study of material from the famous Chicxulub impact crater on the Yucatan Peninsula has finally coincided with the chemical signature of the meteoritic dust of its rock with that of the geological boundary that represents the extinction of dinosaurs.

It seems to be a clear sign that the thin blanket of dust deposited on the Earth’s crust 66 million years ago originated in an impact event at this very site.

“We’re now at the level of coincidence that geologically doesn’t happen without causation,” says geoscientist Sean Gulick of the University of Texas in the U.S.

Together with his geoscientist Joanna Morgan of Imperial College London, Gulick led an expedition in 2016 to retrieve a sample of more than half a mile of shattered rock at the crater’s maximum ring.

Four different laboratories performed measurements on the sample. The results not only help unite a major transition in the fossil record with the site, but also hint at a timeline that supports a rapid decline in dinosaur populations in just a decade or two.

“If you really want to put a watch on extinction 66 million years ago, you could easily argue that it all happened in a couple of decades, which is basically the time it takes for everything to starve,” Gulick says.

Half a century ago, the question of why the diversity of fossils representing the Mesozoic era came to such an abrupt end in the geological record was open. Whoever was responsible for the sudden loss of 75 percent of life on Earth had to be relatively quick and global.

The hypotheses of such a cataclysmic violence focused mainly on two possibilities: one emerging from the subsoil as an increase in volcanic activity, the other from above in the form of a strike of comets or asteroids that radically alter the global climate. .

In 1980, the American physicist Luis Alvarez and his son, a geologist named Walter, published a study of a thin layer of sediment that divides the Cretaceous period populated by dinosaurs from the post-dinosaur world of the Paleogene.

One defining feature of this thin layer of sedimentary rock from millimeters to centimeters thick was an unusually high amount of the element iridium, a metal not found in abundance in the earth’s crust.

One place where you will find plenty of irises is in meteorites. So the discovery of Alvarez and his son was the first solid proof that something in space splattered its remains all over the planet at the time the dinosaur biodiversity was submerged.

Coincidentally, the site of this colossal collision was the focus of ongoing research at the same time, although it established a clear connection between the 180- to 200-kilometer-long (112 to 125-mile) scar on the scar. south shore of the gulf. of Mexico with the killer asteroid would not happen until the 1990s.

Since then, evidence to support the impact of an asteroid has only intensified, with models suggesting the angle, as well as the location of the Chicxulub impact, which played a crucial role. in the magnitude of extinction.

Signs that an area of intense geological activity in western India called the Deccan Traps provided large amounts of greenhouse gases at the time meant that the volcano hypothesis has never been completely ruled out, at least as a possible contributing factor.

It is yet to be debated whether this tectonic hotspot played any role in the famous extinction event or even helped restore biodiversity.

What is no longer a serious point of debate is whether the 12-kilometer-wide piece of rock that hit the coast of what is now Mexico about 66 million years ago is the same one that dusted off the remains of countless dinosaurs.

“The circle is already over,” says study leader Steven Goderis, a geochemist at the Vrije Universiteit Brussel in Belgium.

Case closed.

This research was published in Scientific advances.