After hitting Louisiana with winds of 150 mph, Ida has weakened below the state of tropical depression. But even though the winds are gone, the threat is significant instantaneous flooding it remains as the system pushes northeast. In fact, this threat will only grow as tropical moisture merges with a ray of lightning that sinks south of the Great Lakes.

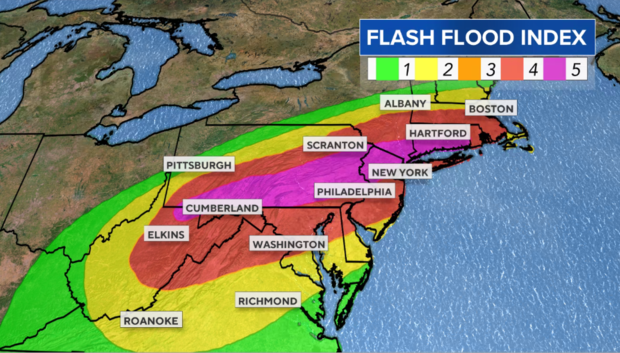

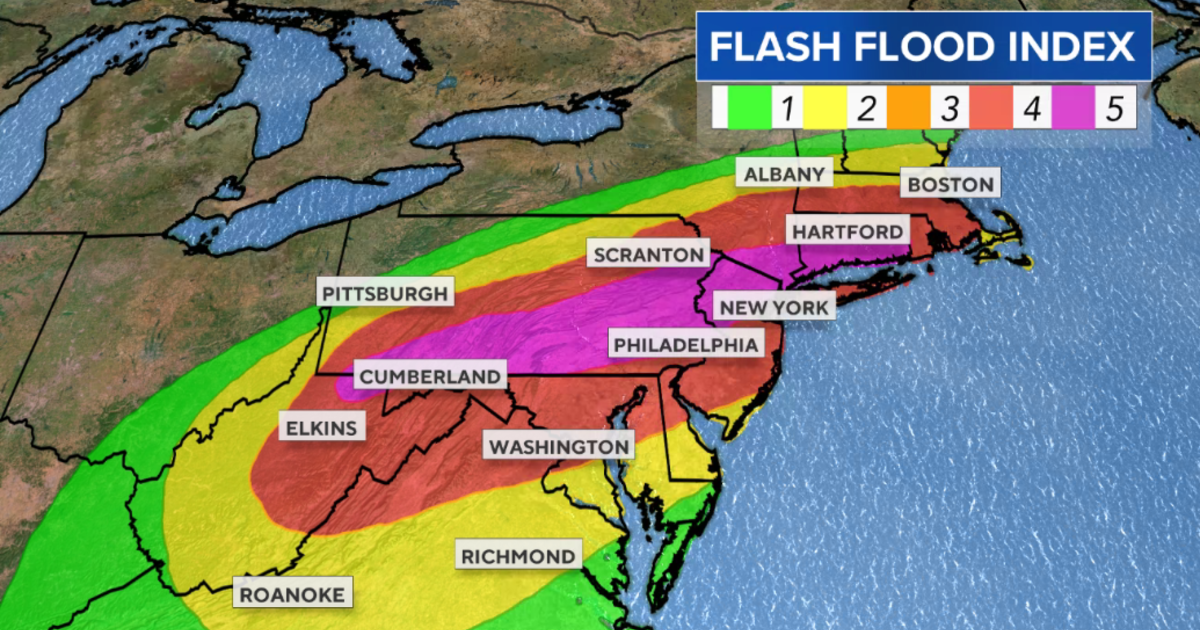

The expectation of widespread rainfall of 4 to 8 inches in some parts of the mid-Atlantic and Northeast has caused the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Weather Forecast Center to emit a rare “high risk” of torrential rainfall. , warning that it could be a 100th Event every year for some areas.

CBS News

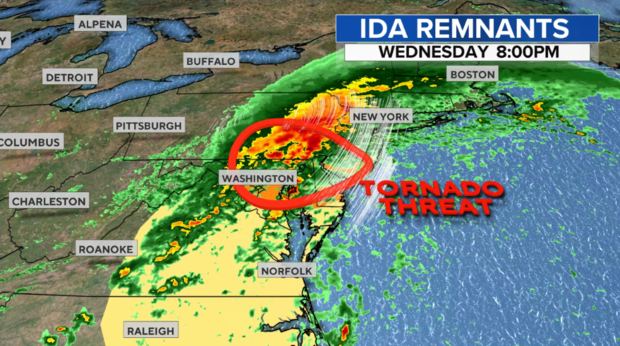

On Tuesday night, the system was located east of the Tennessee Valley and in the central Appalachians. The rain was falling moderately, but it still had to be overfed by the impending lightning current. This will happen Wednesday and Wednesday night.

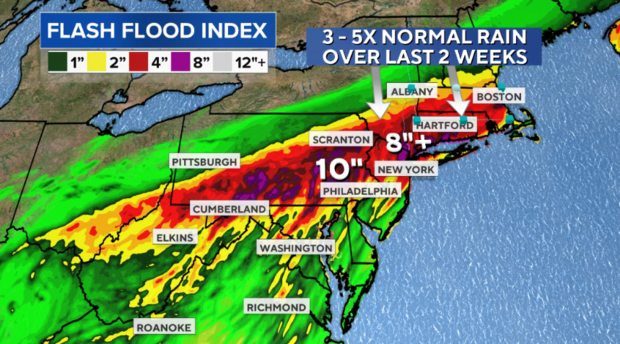

Weather models predict 4 to 6 inches of rain over a wide area, with isolated spots exceeding 8 inches. The heaviest rain appears to fall from the hills of northern West Virginia and Maryland, northeast across Pennsylvania, northern New Jersey, southeastern New York and southern New England. This includes cities like Cumberland, Maryland; Harrisburg and Allentown, Pennsylvania; New York and Hartford, Connecticut.

CBS News

NOAA said that at some points, heavy rainfall can occur that was only expected every 100 years, thus explaining the need for a high-risk outlook. A small number of days each year is designated as high risk, but 90% of all flood damage occurs on these extreme days.

Sometimes, rain will fall at a rate of 2 inches per hour, overwhelming the soil’s ability to absorb water. As a result, the excess will flow down the hills to the growing streams and rivers. To make matters worse, heavy rains have already fallen recently thanks to tropical storms Fred i Henri. Many areas have seen 3 to 5 times normal rainfall in the last two weeks.

Flash flood pockets are almost guaranteed. Areas that are usually flooded in this area can expect streams to overflow, streets to be impassable, and water to be in some houses.

South of the heaviest rain, the combination of leftover turns from the Ida Circulation, the top-level jet stream, and very warm, unstable air on the surface will cause strong storms with some tornadoes. The region most likely to be threatened by tornadoes includes the Philadelphia and Washington, DC areas, later Wednesday through Wednesday evenings.

CBS News

The heaviest rain will fall Wednesday evening through Thursday morning from New York to Boston before leaving New England on Thursday morning.

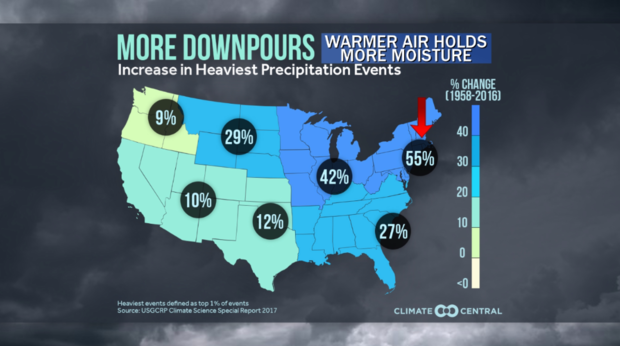

While it’s not uncommon for remnants of tropical systems to shed flooding, heavier rain events have become more common since 1960, especially in the northeast. This is because warming waters along the northeast coast are overload storms and warmer air can contain more moisture, both symptoms of human-induced climate change. The frequency of the heaviest rain events has increased by 50% in the northeast at this time.

Central climate

But the impacts of climate change on Ida are not limited to heavy rainfall. A warmer climate also increases the rate of intensification and intensity of hurricanes, both full-screen with Ida.

While Ida would still have been a major hurricane with no climate change, it is likely that the already warm waters of the Gulf of Mexico would become warmer because of this. Since 1900, temperatures in the tropical Atlantic Ocean have risen 2 degrees Fahrenheit.

Ida boosted to 65 mph in 24 hours, almost double the definition of rapid intensification (RI). RI makes storms like Ida even more dangerous because they leave less time to prepare.

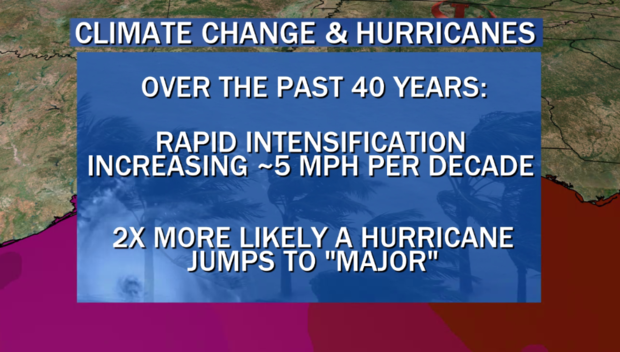

One study found that over the past 4 decades, IR has increased 4.4 mph per decade. This means that if a storm was able to increase its intensity by 40 mph on a 1980 day, it now has the ability to increase its intensity by 55 to 60 mph in 24 hours. Although the authors of this study said the increase was likely the result of a natural cycle of warming and cooling water in the Atlantic, a 2019 study found that climate change is also the culprit.

CBS News

In addition, hurricanes are becoming stronger around the world and especially in the Atlantic Ocean. There has been a steady trend in recent decades of a larger proportion of major hurricanes: Category 3, 4 and 5. This is because for every 2 degree increase in water temperature, the intensity of a hurricane can increase by about 20 mph.

In the Atlantic, front-line hurricanes now have twice the chances of jumping into major hurricanes a few decades ago. This is due to the warming of the waters, not only of the greenhouse gases that capture heat, but also of the decrease in air pollution across the Atlantic, which a few decades ago would block most of the sun and it would dampen the ability of tropical cyclones to intensify.

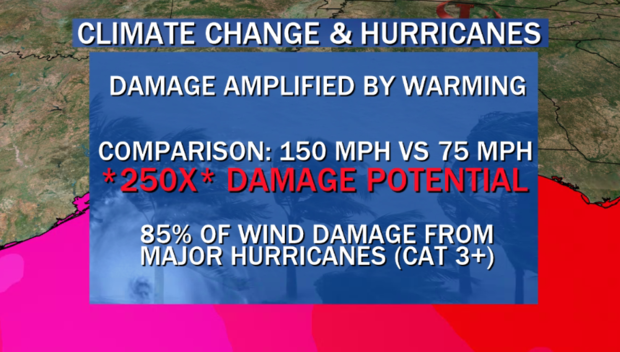

These changes in intensity make a big difference because the damage does not tend to line upwards with increasing wind speed. In contrast, the potential for damage increases exponentially as the winds strengthen. Therefore, comparing a storm with winds of 75 mph to one with winds of 150 mph means that the damage is not doubled; perhaps surprisingly, the potential for damage increases 250 times.

CBS News

Although major hurricanes account for a lower proportion of tropical storms than weaker ones, major hurricanes cause the vast majority of damage, about 85% according to NOAA.

By the middle of the 2021 hurricane season, we are already well ahead of the normal pace. If the record season of 2020 is a guide, the second half of the 2021 hurricane season will be active, with the possibility of more intense storms.