There are a handful of numbers throughout baseball history that are so important, so revered, so iconic that they require no further explanation. 714 i 755 counts there, as well .406 or 56 in a row. If we move from baseball card statistics to uniform numbers, then 42 he is also part of this club. You will soon know what all these mean.

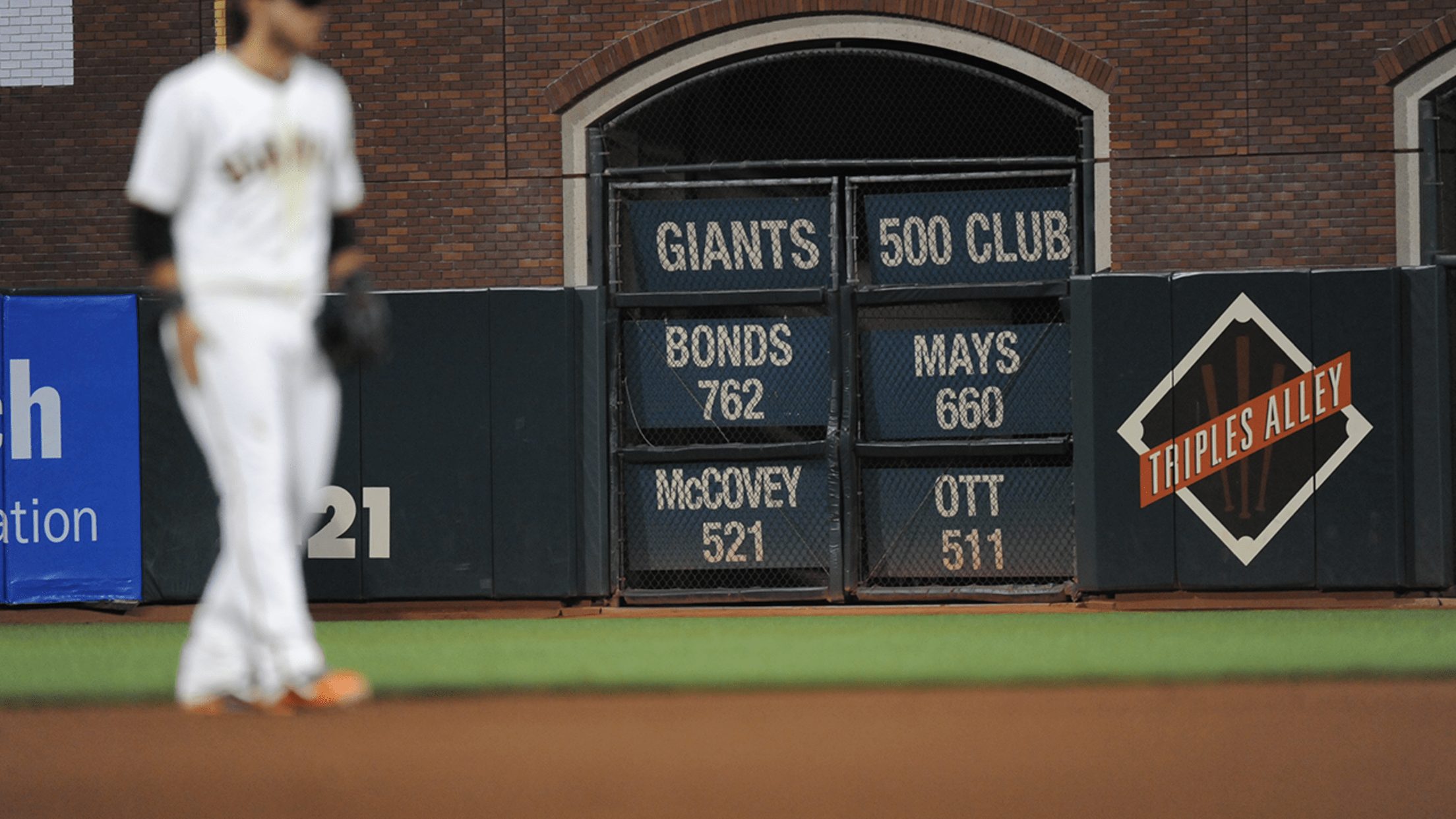

For almost 50 years, 660 it has also been one of those numbers. Willie Mays reached the 660th and final regular season of his regular career on August 17, 1973 at Shea Stadium as a member of the Mets against Cincinnati’s Don Gullett. Of course, he got one in the playoffs (’71), and three more in the All-Star Games (’56, ’60 and ’65), and surely there are countless more in Spring Training and other exhibitions, but 660 is the number. It is located on the plaque of the Hall of Fame. It is in some of his autographs. It is written on the wall of Oracle Park. When someone passes the 660, it’s a big deal. He is as related to Mays as the 24 he wore on his back.

This number 24 will never change. But in 660, believe it or not, you could. Forty-seven years after Mays last played professional baseball, he could have won another dinger. How 661 so?

What we are about to explain is not a stone, of course. There is a lot of research, clarification, approval and updating to do. But as the research continues, so does our understanding of the historical record.

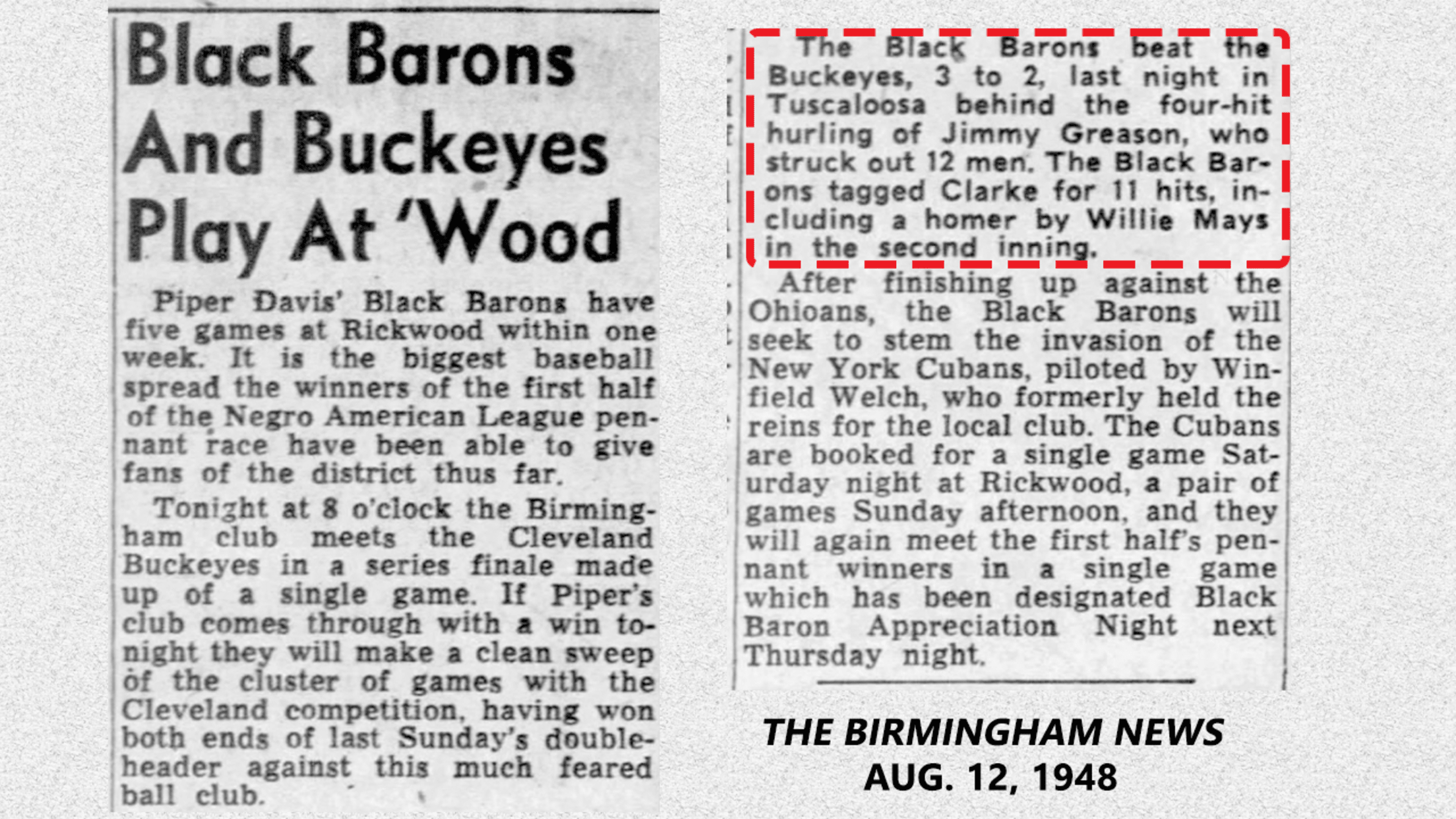

“We have that home run … 1948 by Willie Mays,” Larry Lester, a prominent Black League historian, said on Thursday’s episode of the Ballpark Dimensions podcast. “We’ll add it; it’ll have 661. We found this score in the box.”

So long, 660, hello 661? That would be groundbreaking. Let’s explain how we got here.

On December 16, Major League Baseball announced that the Black Leagues, specifically a group of seven leagues that they were active between 1920-48, would receive the condition of Major League. This was done to rectify the wrong decision of a “Special Committee on Baseball Records” which met in 68 and gave four historic leagues (along with the current American and American leagues) the Major League status, but did not even consider the Black Leagues. This designation had long since been late and was not necessary to recognize that black and Latino players from generations ago were not minors and should not be forgotten.

“It gives extra credibility to the importance of black leagues, both on and off the field,” said Bob Kendrick, president of the Black League Baseball Museum, that these men and women, from players to owners, didn’t need. the validation of anyone. For me, this baseball move is more about correcting a mistake, ”she told legendary sports writer Claire Smith.

This immediately opened the world of baseball to a lot of questions about how the inclusion of Black League statistics could change the numbers we all know. For example, Joe Tinker’s Hall of Fame career statistics include his time in the National League. i his two years in the launched Federal League of 1914-15, which is considered a Major League. He has 31 professional home runs, which are a combination of “29 in the National League and two in the Federal League.” By contrast, the pages of Major League legend players such as Mays, Jackie Robinson and Larry Doby do not include Black League numbers: yet, anyways.

As we have tried to speculate, using the Black League database compiled at Seamheads.com, it appears that including these statistics may have some significant effects on the all-time leaderboards. Josh Gibson will not be the all-time leader at home, but he could have the best batting average of a single season (.466 in 1943). There will be about two dozen new non-hitters, including Leon Day joining Bob Feller as the only men to have launched Opening Day no-days. There will be many such changes to come.

But this work is not yet complete, as only about 75% of the cash scores of known Black League games between 1920 and 48 have been collected and cataloged in the Seamheads database. Without a cash score, there will be no official number, even if an event is known to have happened. Like, say, an extra home run for Willie Mays. Mays played briefly for the 48 black Birmingham Barons, and on his Seamheads page there is no home run. But as Ben Lindbergh pointed out, he deserves great credit for bringing the issue of Black League status to the forefront this summer, this week:

“Mays delved at least once into his rookie campaign for the Black Barons, but no cash score has been found. Until none of them are located, his famous 660 home run mark will remain the same.” .

And that, we imagined, was that. That Mays man was likely to miss 25% of the cash scores. It could be years before it is found. May be May Be found. Six hundred and sixty will go nowhere, soon.

THE 660 RACE MARKET AT CASA DE MAYS IS PROMINENTLY SHOWN ON THE RIGHT FIELD IN ORACLE PARK. (CREDIT: GIANTS SF)

Except for … Thursday, we invited Lester to join the podcast to discuss the process for getting to this point and how the news affected him. After all, Lester is a co-founder of the Black Leagues Baseball Museum and chair of the Black Leagues Committee of the Society for American Baseball Research (SABR). He is an experienced author and publisher in many fields, and is one of the most prominent researchers in the Black League. It is likely that none of this would have been possible without his efforts.

When we raised the point of the missing box scores, he agreed but said there would be more to come.

“We’ve found more than that,” Lester said, “but right now we only have about 75% in the database.”

We knew immediately that our speculative assumption about how the number would change, such as Gibson’s possible .466, its 200 OPS + or Satchel Paige’s 1,563 additional entries, was incomplete. These numbers can and will change as more information is entered.

“We probably found 99% of the games in the 1920s, and the 1930s are a success. In the 1940s and late 1930s, we found probably 90% of the games that were scheduled,” Lester continued. . “We’re in good shape. It takes a while to restrict the numbers. All the lines in this box have to be entered manually into a spreadsheet, which is uploaded to a database I’ve created.

“And this information from the database goes to Gary Ashwill with Seamheads, so that this data is available to everyone on the Internet. We’ll get there and change some of the records, bad bad and indifferent. Some people will be upset to find out that Josh Gibson never reached 800 home runs. “

But the real news was not the one that has not yet been found. It’s what has – the one missing from Mays house.

That home run was hit on August 11, 1948, when Mays reportedly spent about three months of his 17th birthday. As Lindbergh pointed out, that home run was mentioned in the newspaper news. She arrived in Birmingham and, if this news is accurate, was run over by 20-year-old Panamanian Vibert “Webbo” Clarke of the Cleveland Buckeyes. (Clarke would later appear briefly in seven games for the Washington Senators of ’55).

Therefore, if the box score exists and has not yet been entered into the system, it seems likely that it will be soon enough. (While the process continues, the MLB and Elias Sports Bureau, the official MLB statistician, are convening an official review to determine how to proceed.) The Mays will have 661 Major League homers: 660 National League homers and one in Black. Leagues. One regular season home run, anyway.

“We also have a home run that he achieved in the third game of the World Series in 1948,” Lester continued. “There was no scoreboard. Albert Pujols is safe right now with 662 … but he still doesn’t count me. I’m still looking.”

Of course, Pujols also has 19 home runs in the postseason, and we do not count those of his professional career. Six hundred and sixty-one, if and when is what Mays ends up with, they seem to be safe.

In 2015, the New York Times recounted Mays’ last run at home in a story titled “On the Night Willie Mays Hit No. 660, It Was Just Another Number,” noting that he had little fanfare because he didn’t break records. and with six weeks to go before the season was over, no one knew it would be the last; functionally, he was no different from number 657 or number 648. It will always be his last shot at home, but perhaps the Times was more correct than they knew. Maybe yes era just one more number.

Mike Petriello is an MLB.com analyst and host of the Ballpark Dimensions podcast.