Vegetarian and vegan options have become a standard fare on the American diet, from exclusive restaurants to fast food chains. And many people know that the food decisions they make affect their own health and that of the planet.

But on a daily basis, it’s hard to know how many individual options, such as buying mixed vegetables at the grocery store or ordering chicken wings at a sports bar, can translate into overall personal and environmental health. This is the gap we hope to fill with our research.

We are part of a team of researchers with experience in food sustainability and environmental life cycle assessment, epidemiology and environmental health and nutrition. We are working to gain a deeper understanding beyond the often overly simplistic diet debate about animal versus plant diet and to identify environmentally sustainable foods that also promote human health.

Based on this multidisciplinary experience, we have combined 15 nutritional health-based dietary risk factors with 18 environmental indicators to evaluate, classify, and prioritize more than 5,800 individual foods.

Ultimately, we wanted to know: Do we need drastic dietary changes to improve our individual health and reduce environmental impacts? And does the entire population need to be seen to make a significant difference to human and planetary health?

Put difficult numbers in food choices

In our new study in the research journal Nature Food, we provide some of the first concrete figures on the health burden of various food options. We analyzed individual foods based on their composition to calculate the net benefits or impacts of each food.

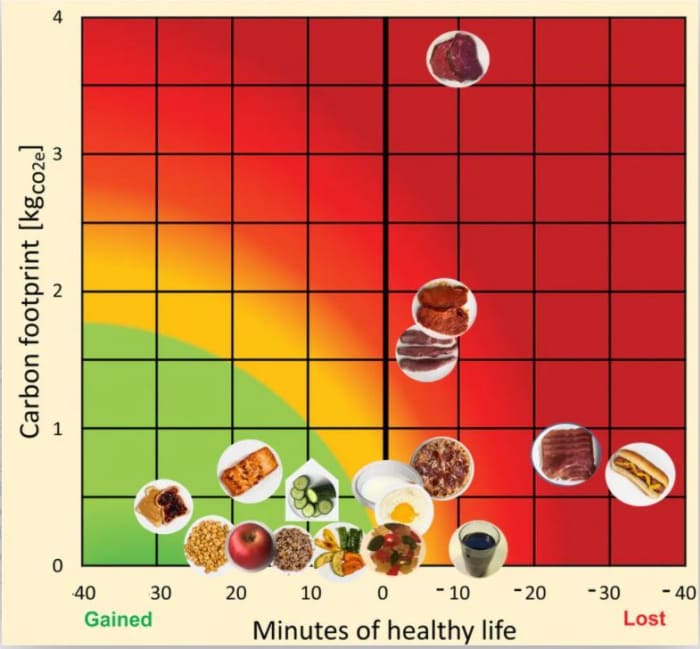

The health nutrition index we have developed turns this information into minutes of life lost or gained per serving of each food consumed. For example, we found that eating a hot dog costs a person 36 minutes of “healthy” life. In comparison, we found that eating a 30-gram serving of nuts and seeds provides a 25-minute gain in healthy living, that is, an increase in good quality, disease-free life expectancy.

Our study also showed that replacing only 10% of the daily caloric intake of beef and processed meats with a diverse mix of whole grains, fruits, vegetables, nuts, legumes, and select seafood could reduce, on average, the dietary carbon footprint of an American consumer a third and add 48 minutes of healthy living a day. This is a substantial improvement for such a limited dietary change.

Foods with a good score, shown in green, have beneficial effects on human health and a small environmental footprint.

Austin Thomason / Michigan Photography and University of Michigan, CC BY-ND

How did we break the numbers?

We based our health nutrition index on a comprehensive epidemiological study called Global Burden of Disease, a comprehensive global study and database that was developed with the help of more than 7,000 researchers from around the world. The overall burden of disease determines the risks and benefits associated with multiple environmental, metabolic, and behavioral factors, including 15 dietary risk factors.

Our team took these epidemiological data at the population level and adapted them to the individual food level. Taking into account more than 6,000 specific risk estimates for each age, sex, disease and risk, and the fact that there are approximately half a million minutes a year, we have calculated the health burden of consuming one gram of food. for each of the dietary risk factors.

For example, we found that, on average, 0.45 minutes per gram of any processed meat a person eats in the U.S. is lost. We then multiplied this number by the corresponding food profiles we developed earlier. Going back to the example of a hot dog, the 61 grams of processed meat in a hot dog sandwich results in a healthy 27-minute loss of life due to just that amount of processed meat. Then, considering the other risk factors, such as sodium and trans fatty acids within the hot dog, offset by the advantage of fat and polyunsaturated fibers, we reached the final value of 36 minutes of healthy life lost by hot dog .

We repeated this calculation for over 5,800 foods and dishes combined. We then compared health index scores with 18 different environmental metrics, including the carbon footprint, water use, and impacts on human health induced by air pollution. Finally, using this health and environmental nexus, we color-coded each food as green, yellow, or red.

Like a traffic light, organic foods have beneficial health effects and a low environmental impact and should be increased in the diet, while red foods should be reduced.

Where are we going from here?

Our study allowed us to identify certain priority actions that people can take to improve their health and reduce their environmental footprint.

In terms of environmental sustainability, we have found surprising variations both within and between foods of animal and plant origin. For “red” foods, beef has the largest carbon footprint in its entire life cycle, twice that of pork or lamb and four times that of poultry and dairy products. From a health standpoint, eliminating processed meat and reducing overall sodium intake provides the biggest gain in healthy living compared to other types of foods.

Therefore, people might consider eating less foods rich in processed meat and beef, followed by pork and lamb. And, above all, among plant-based foods, greenhouse-grown vegetables have had a poor result in environmental impacts due to heating combustion emissions.

Foods that people might consider increasing are those that have high beneficial effects on health and low environmental impacts. We have observed a lot of flexibility between these “green” options, including whole grains, fruits, vegetables, nuts, legumes, and fish and seafood of low environmental impact. These items also offer options for all income levels, tastes and cultures.

Our study also shows that when it comes to food sustainability, it is not enough to consider only the amount of greenhouse gases emitted, the so-called carbon footprint. Water-saving techniques, such as drip irrigation and reuse of gray water, or domestic wastewater, such as sinks and showers, can also take important steps toward reducing the water footprint of food production.

One limitation of our study is that epidemiological data do not allow us to differentiate within the same food group, such as the health benefits of a watermelon compared to an apple. In addition, individual foods should always be considered in the context of the individual diet, given the maximum level above which foods are no longer beneficial: you can not live forever just by increasing the consumption of fruit.

At the same time, our nutritional nutrient index can be adjusted regularly, incorporating new knowledge and data as they become available. And it can be customized worldwide, as has already been done in Switzerland.

It was encouraging to see how small, specific changes could make such a significant difference to both health and environmental sustainability, one meal at a time.

Now read: Maybe you can live longer by eating fewer calories. But should you do it?

Too: Here’s how to look beyond “Live at 110!” advertise and be smart when it comes to digesting the latest research on longevity

Olivier Jolliet is a professor of environmental health sciences at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. Katerina S. Stylianou is an associate researcher in environmental health sciences, also at the University of Michigan. This was first published by The Conversation: “Individual dietary options can add to or take away minutes, hours, and years of life.”