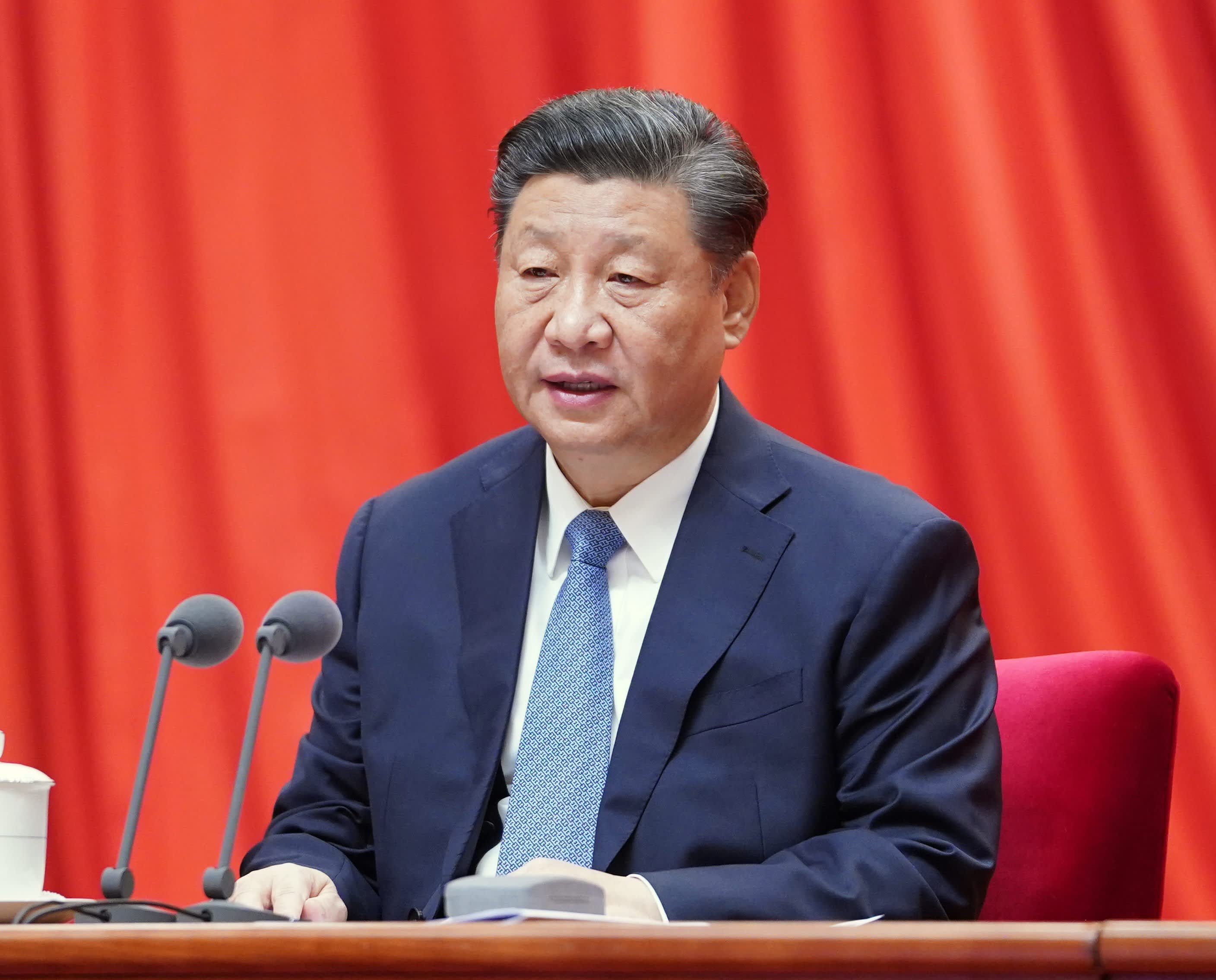

Chinese President Xi Jinping in Beijing on January 22, 2021.

Shen Hong | Xinhua News Agency | Getty Images

GUANGZHOU, China – China is trying to tighten rules on how the personal data of its citizens are collected, as it moves to further curb the power of technology giants like Alibaba and Tencent.

A solid data framework could help countries also define how the next-generation Internet looks, said one expert, who noted that it could become a geopolitical issue as China wants to challenge the United States in the field. technological.

But the move has also sparked debate over whether these same rules will apply to one of the country’s largest data processors: the government.

Last year, Beijing released the draft version of the Personal Information Protection Act (PIPL), which established for the first time a comprehensive set of rules on data collection and protection. Previously, several partial legislations regulated the data.

It is seen as part of a larger effort to curb the power of Chinese technology giants that have been able to grow seamlessly in recent years through the vast collection of data to train algorithms and build products, the experts.

… Users are more knowledgeable and angry with companies that abuse their personal information.

Winston Ma

New York University School of Law

In February, China issued revised antitrust rules for companies called “platform economy,” which is a widespread term for Internet companies operating a variety of services, from e-commerce to food delivery.

“The government wants to curb some … of these tech giants,” Rachel Li, a partner at Beijing-based Zhong Lun’s law firm, told CNBC by telephone. “This legislation … goes along with other efforts like antitrust.”

Data protection rules

Globally, there has been a push for more robust rules to protect consumer data and privacy as technology services continue to expand.

In 2018, the General Data Protection Regulation of the European Union entered into force. Briefly called GDPR, it provides blog citizens with more control over their data and gives authorities the ability to fine companies for non-compliance. The US has not yet enacted a national data protection law like Europe.

Now China is trying to do something similar.

“After years of Chinese internet companies building business models around Chinese people’s lack of awareness about privacy, users are becoming more knowledgeable and angry with companies that abuse their personal information.” , Winston Ma, an adjunct professor of law, told CNBC by email.

China’s personal information protection law applies to citizens of the country and to companies and individuals who manipulate their data.

The following are the key parts of the law:

- Data collectors must obtain the user’s consent to collect information and users have the right to withdraw that consent;

- The companies that process the data may not refuse to provide services to users who do not consent to the collection of their data, unless such data is necessary for the provision of this product or service;

- Strict requirements and rules for data transfer of Chinese citizens abroad, including government permission;

- Individuals can request their personal data from a data processor;

- Any company or person who violates the rules cannot receive a fine of more than 50 million yuan ($ 7.6 million), or 5% of annual turnover. They might also be forced to leave some of their businesses.

What it means for the technology giants

In general, the age of “exponential growth in the desert” for the expansion of Chinese technology companies, whether domestic or foreign, is over.

Winston Ma

New York University School of Law

But there are signs that the scrutiny could be extended. Reuters reported last month that Pony Ma, the founder of gaming giant Tencent, met with antitrust officials to discuss compliance with his company. Tencent owns the social networking application WeChat, which has become ubiquitous in China.

NYU’s Ma noted that the data protection law will have a “balanced approach to the relationship between individual users and Internet platforms.” But, combined with other regulations, it could slow the growth of tech giants, he said.

“Overall, the era of‘ exponential growth in the desert ’is over for the expansion of Chinese technology companies, whether domestic or foreign,” he said.

He added that some companies may be forced to change their business models.

“Geopolitical factor”

Experts previously told CNBC that China’s push to regulate its internet sector is part of its ambition to become a technology superpower as tensions between Beijing and Washington continue. Data protection regulation is part of that momentum.

“To a large extent, cyberspace and the digital economy remain undefined, the framework of data law has become a geopolitical factor,” said Ma of NYU. “Any country that can take the lead in making progress in legislation or its development model can provide a model for the next generation of the Internet.”

Ma said that if there is a digital economy version of World Trade Organization rules, countries with strong data laws can have “leadership power.” The WTO is a group of 164 member states that aims to create rules around world trade.

“That’s why they’re talking more and more about what the Chinese model is.”

Possible contradictions

Chinese data protection law contains a section on state agencies that process information.

In theory, the state should adhere to similar principles around data collection as a private company, but there is debate as to whether this is the case.

“We often think of PIPL in terms of its applications on Alibaba or Tencent, but we forget that China’s state agencies are the country’s largest data processors,” said Kendra Schaefer, a partner at Trivium China, a Beijing-based research.

“There is a lively debate in the Chinese legal and academic communities about how the PIPL should be applied to administrative activities,” he said. “A specific issue is that the PIPL gives people the right to give informed consent when their data is collected, but this can conflict with, for example, police investigations by law enforcement.”

“What’s interesting is that it starts a national conversation around what the Chinese government may or may not do with citizen data and how the law should define state obligations,” Schaefer added.