Sthe theory of imitation raises that the reality could not be real, but could be an illusion that we do not know and from which we can wake up, and is an idea investigated by all from Plato (with “The cave”) and Descartes (with Meditations on first philosophy), more recently, to Philip K. Dick and The matrix. It is a fantasy of escape and enslavement, liberation and manipulation, which delves into our own experiences moving between conscious and unconscious states, as well as getting lost in the fictional world of cinema. As such, this is just the ideal theme for documentary filmmaker Rodney Ascher, which to perfection Room 237 (About Brightness-as-box-puzzle-multifaceted) i The nightmare (about sleep paralysis) ventures back into unreal terrain with A problem in the array, a compelling look out for the possibility that we are all avatars in a game we can’t understand.

Dick’s 1977 speech in Metz, France, entitled “If You Find This World Bad, You Should See Some of the Others,” is the backbone of A problem in the array (premieres in the Midnight section of the Sundance Film Festival on January 31, followed by a VOD debut on February 4). In it, the famous author of A dark scanner, The man from the high castle, Minority report, Androids dream of electric sheep? (the basis for Blade Runner), i We can remember it in bulk (the basis for Total recovery) confesses that a 1974 dose of Sodium Pentotal for impacted wisdom teeth allowed him to have an “acute flash” of a “recovered memory” about a world and a life that was not his. Dick wrote extensively about this experience (known as “2-3-74”) in the posthumous publication The exegesis of Philip K. Dick, and also reported on his fictional production, much of which confronted the unreliable and volatile nature of reality, imagining future societies in a prophetic and poignant way.

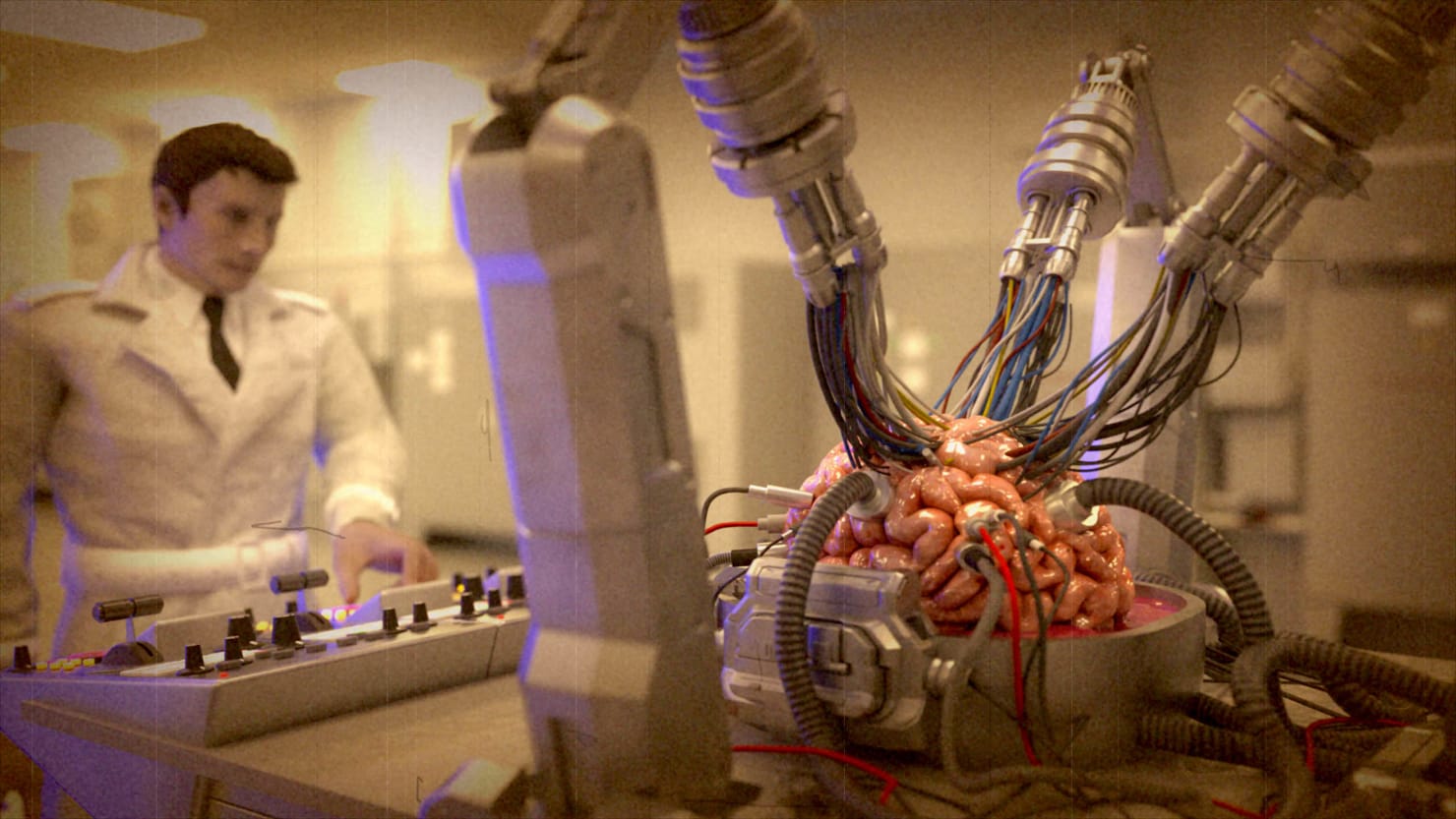

Dick was the modern godfather of simulation theory and A problem in the array he spends a lot of time with people who have written his first writings, as well as that of Lana and Lilly Wachowski The matrix, himself intensely indebted to Dick, with the heart. In Skype interviews with Ascher, these individuals appear disguised as extravagant digital avatars, including a red-faced armored lion, a Mechagodzilla-ish dragon in a tuxedo, a vaping alien in an inflated space suit, and a helmeted warrior with eyes. and digital mouth. . His appearances speak of his own belief in dueling realities (and identities), which also stems from Elon Musk’s public conviction that we could live in an artificial simulation led by advanced beings, as well as in a 2003 academic paper Oxford University. Professor Nick Bostrom (“Do you live in a computer simulation?”) who advanced the hypothesis that we could be pawns in a hyper-advanced program that recreates a past that has already occurred (called “ancestral simulation”), or alternative chronology totally new.

The notions sent by these speakers depend on everything from anecdotal stories about their own breaks with reality, to arguments about coincidences, probabilities and synchronicities, to scandalous speculations – and very specific – about the details of our simulation. . Suffice it to say that not everything is convincing. However, it is amusingly insightful about humanity’s continuing desire to explain great mysteries through spiritual scientific concepts for foreign realms, higher powers of puppeteers, and technological exploitation.

To his credit, one interviewee (Paul Gude also known as the “lion”) admits that perhaps simulation theory is simply the simplest means by which his brain chooses to cope with the complexity of human existence. And in an earlier scene, he admits that his theory based on virtual reality may be a byproduct of the fact that people are always trying to explain reality using the most advanced technology available at the moment. It presents clips of films of, among others, The Wizard of Oz, The Truman show, A nightmare on Elm Street, Vertigo, The thirteenth floor, The Adjustment Office, They live, Defending your life and of course The matrix, A problem in the array suggests that films are a primary vehicle for both creating and channeling these ideas, which are often rooted in feelings of loneliness, alienation, and despair, and can therefore lead to especially appalling consequences.

“As Cooke’s story makes clear, the danger of simulation theory is that if nothing and no one is genuine, ethical concerns about society and your man are irrevocably undermined, causing potential chaos.”

This is expressed most distressingly by an extensive sequence in which Joshua Cooke explains (through an audio interview, complemented by CGI recreations) how his love for The matrix, along with his abusive domestic life and his undiagnosed mental illness, led him to murder his adoptive parents in an attempt to discern if he was in fact living within the Matrix (his conclusion: “I was very wrapped up. bad, because it wasn’t There was nothing like what I had seen The matrix. What a real life it was so much more horrible. It bothered me a little ”).

Cooke was 19 when he killed his adoptive parents with a 12-caliber shotgun in Virginia, and later pleaded guilty and was sentenced to 40 years in prison. It became known as “The Matrix Case” and, as Cooke’s story makes clear, the danger of simulation theory is that if nothing and no one are authentic, ethical concerns about society and your man are undermined inexorably, leading to potential chaos. Unsurprisingly, the links between video games and simulation theory are numerous — Jesse Orion (that is, the alien astronaut) says he spent years doing little more than playing games — and A problem in the array access this connection by using all kinds of computer animated graphics (including Google Earth and Minecraft) to visualize the assumptions of your subjects. Illuminating and entertaining, the film’s digital playful form reflects and reveals truths about its content.

It sets Jonathan Snipes ’menacing electronic score and also deals with the way déjà vu and“ The Mandela Effect ”relate to its central theme, A problem in the array continues Ascher’s nonfiction study of common tales, scientific hypotheses, and art analysis. Offering a chorus of voices seeking to decipher the riddles of the universe and the atom through fantastic looks at the mind, body, and reality itself, his film is an open and astutely critical investigation of our evolving perceptions. of who we are, our deeply personal connection to big screen dreams, and our persistent search for knowledge about things we (still) don’t understand. It is a treatise on religious and scientific aspirations, and on human impulses and aspirations, which serves as a portrait of conspiracy theories and mass deception.