The sacristy, a small room next to the altar, is full of bad memories. Dozens of worshipers sought refuge here while terrorists besieged the church. Many were shot or killed by grenades, leaving blood-stained handprints left on the walls. Natiq, as well as his wife and son, were among them.

Today, the church of Our Lady of Salvation is adorned with the engraved names of the murders that day: 51 congregants and two priests.

The attack left Anwar partially blind, with his right arm badly injured.

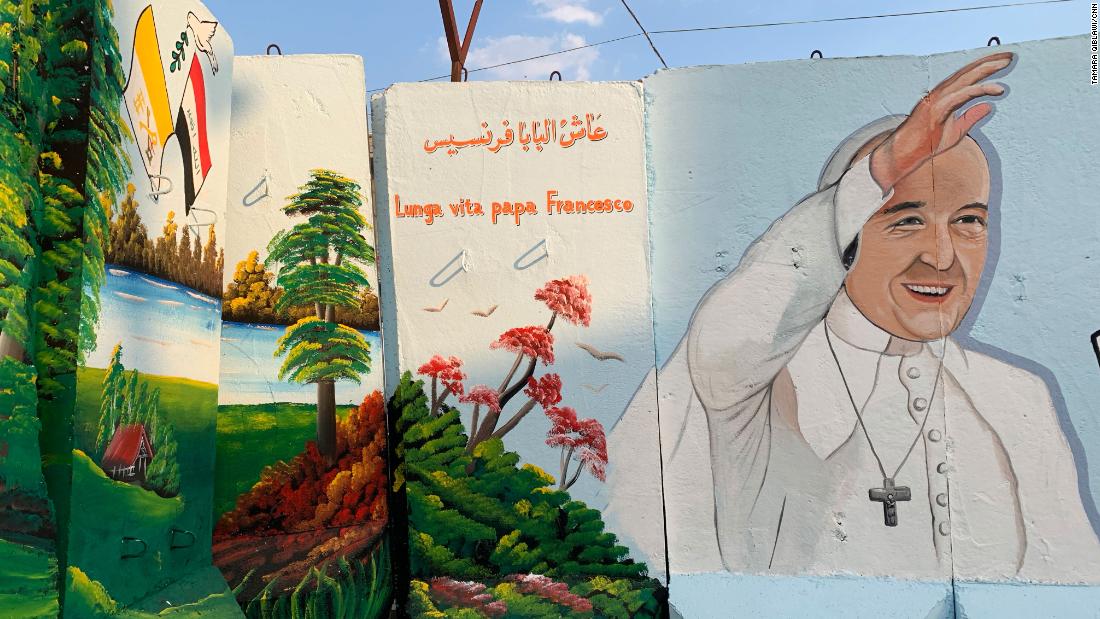

With his eyes half closed, he looks towards a new addition to the church: a white throne, located under an imposing collage of martyrs of the parish. Pope Francis will make a speech here when he arrives in Iraq on Friday.

“I’m very happy. I’m very, very happy,” Anwar said, looking forward to the visit. Despite his effusive words, the concierge seems a little puzzled. “I want to tell him to take care of us,” he added, “because the state doesn’t take care of us.”

But Anwar will not be one of the small gatherings of church members to greet the pontiff during his historic visit. Due to the pandemic, the crowd stays away.

The vast majority of Iraqi Christians will watch the tour – the first by a pontiff to Iraq – on television. A full curfew is being imposed for the duration of the trip.

These strict measures have been taken to mitigate the risks of the visit, which is considered the most dangerous trip so far by Pope Francis, both for the increase in cases of coronavirus at the national level and the increase in violence in the country. devastated by war.

“Pope Francis coming to Iraq highlights the importance of our country to the faithful around the world,” a senior official in the president’s office said. “It ‘s also a statement from [the] Pope’s support for peace in Iraq, a testament to the reverence of Iraqi Christians.

“This visit comes at a difficult time for Iraq, but we are taking all necessary precautions for the coronavirus,” the official said.

The trip, announced last December, was expected to be canceled.

The rise of the country’s Covid-19 also continues unabated: last weekend, the Vatican’s envoy to Iraq, Mitja Leskovar, tested positive for the virus.

Still, the pope insists he will not disappoint Iraqis.

At the end of a general hearing on Wednesday, the pontiff made no mention of the deteriorating security situation in Iraq, but said: “For a long time I wanted to meet those people who suffered so much and know that Church. martyred “.

“The people of Iraq are waiting for us. They were waiting for Pope John Paul II, who was not allowed to go,” he said, referring to a planned trip in 2000 that was canceled after a breakdown of talks between the Vatican and then President Saddam Hussein. “You can’t disappoint people a second time. We pray that this journey can go well.”

The Vatican called the trip “an act of love.”

“All precautions have been taken from a health point of view,” Vatican spokesman Matteo Bruni told reporters on Tuesday. “The best way to interpret the journey is as an act of love; it is a gesture of love from the Pope to the people of this land who need to receive it.”

This is a message that is true for many Iraqis.

In addition to Our Lady of Salvation, Pope Francis will visit several sites related to some of Iraq’s worst tragedies in its decades of turmoil, including Mosul, the largest city occupied and devastated by ISIS.

He will also hold a meeting at a cathedral in the city of Qaraqosh, mostly Christian in the north. ISIS turned the courtyard of the Church of the Immaculate Conception into a shooting range. They set fire to the contents of the church, blackening the interiors and destroying their statues. ISIS members piled up bibles, books and prayer books from the church and set them on fire. There is a large black spot in the yard, which marks the place where they were burned.

Iraqi Christians want the pontiff to heal his wounds. But they also hope the trip highlights the plight of their increasingly small community. Prior to the 2003 U.S. invasion, there were 1.5 million Christians in the country. About 80% of them have fled the country, according to major Christian clergy.

“What scares me is that during this period no one has asked what we have lost, for example,” Bashar Warda, the Chaldean archbishop of the northern city of Erbil, told CNN. “We have a declining number of Mandeans and now Yazidis, Christians.

“They don’t care about that,” he said in reference to Baghdad’s political elite. “How they didn’t care when we lost the Jewish community in the 40s, 50s and 60s. And this cycle is underway.”

Sabah Zeitoun moved to Sweden, now home to a large Arab Christian community, about 21 years ago. He returned to Erbil for a visit and extended his journey so that he could be here on the Pope’s tour.

He believes that those who have left the country have definitely gone. “I don’t think anyone will come back from Europe,” the 65-year-old said. “That would be difficult.”

Zeitoun was a soldier for eight years during the Iraq-Iran war in the 1980s. It was deployed in Kuwait during the invasion of the country by former Iraqi President Saddam Hussein.

When he returned, he opened a liquor store in Mosul. In 2000, he said he was arrested and detained for three days for keeping the store open five minutes after the legally sanctioned closing time by the country. That was when he decided to leave Iraq.

‘A peace mission’

In a bustling Baghdad cafe, a young engineer and a political scientist meet deeply in a serious discussion about the Pope’s visit. The conversation between the two young Shiite Muslims began as a joke about the three-day closing, but quickly turned into a conversation about the regional implications of the trip.

“People, both Christians and Muslims, see the Pope as a man of peace,” said political scientist Mumen Tariq, 30. “This visit gives Iraq a new role on the world stage.”

There is surprising hope in his vision of the political situation in Iraq. “The pope’s visit comes at a very important time,” said engineer Mohammed Al-Khadayyar. “It is reaching the grave of the Islamic State and what it will mark is to wait for the beginning of the page of peace. It will push us away from the regional fault lines and reach a place of moderation.”

Asked if they were bothered by the blockade preventing the state, Tariq said, “We are ready to spend three days, a week, 10 days or even a month, if the Pope’s mission is for peace.”

Back at the Church of the Salvation, a handful of congregants are decorating the manger of the courtyard in preparation for the visit. Two veiled Shiites ask to enter the church but are detained for security reasons. Deacon Louis Climis explains that Muslims come here regularly to pray.

A nun regrets that the Pope is not expected to visit a small museum set up in the churchyard to commemorate the massacre, but the rest of the congregants are willing to keep their hopes for the next visit under control.

“The Iraqi Christian means to the Pope that we are sick and in need of medicine,” said Climis, who also survived the massacre. “We need guidance because we’re in a jungle, a mess ruled by political monsters.”

The massacre deepened the Christian faith of janitor Anwar, but eroded his faith in the Iraqi authorities.

For years, he compiled papers seeking government compensation for his injuries, as he had to give up his carpentry career as a result of the attack. Then, one day, he stopped looking for government reparations.

“I gathered the papers in a pile and soaked them in alcohol,” Anwar said, reproducing the scene with his hands. “And then I set them on fire.”

CNN’s Delia Gallagher contributed to this report from Rome. CNN’s Arwa Damon and Aqeel Najm contributed to this Baghdad report.